Submitted by Brent Johnson of Santiago Capital.

Executive Summary

Throughout history, governments around the world have occasionally resorted to confiscating the assets of their citizens in response to economic crises, political purges, or ideological pursuits. These actions, often justified as necessary for the greater good, have frequently resulted in widespread social disruption and significant hardship for the affected populations.

This report delves into four significant historical episodes of asset confiscation, examining the methods used by governments to seize property and the diverse strategies individuals and communities employed to resist or evade these confiscations. Each case provides insight into the complex relationship between state power and personal property rights, as well as the resilience of the human spirit in the face of adversity.

One of the most notorious examples of asset confiscation occurred in the Soviet Union under the leadership of Joseph Stalin.

As part of his larger effort to transform the Soviet economy and eliminate potential opposition, Stalin launched campaigns of collectivization and dekulakization. The government forcibly consolidated individual landholdings into collective farms (kolkhozes) and state farms (sovkhozes), seizing land, livestock, and other assets from the peasantry.

Wealthier farmers, known as kulaks, were particularly targeted as class enemies. The methods of confiscation were harsh and systematic, ranging from forced collectivization to the seizure of grain and livestock.

Despite the brutality of these measures, many peasants engaged in acts of defiance. Resistance took various forms, including hiding grain and livestock, sabotaging government efforts, and fleeing to urban areas in search of refuge.

A parallel can be drawn to the Chinese Cultural Revolution, which took place from 1966 to 1976.

During this period, Chairman Mao Zedong’s government sought to enforce radical socialist policies, resulting in widespread confiscation of assets, particularly from intellectuals, landlords, and those accused of harboring bourgeois values. The Cultural Revolution, led in large part by Mao’s Red Guards, was a time of immense social upheaval, characterized by public denunciations, property seizures, and the internment of perceived enemies of the state in re-education camps.

Common strategies included hiding valuable possessions, falsifying records to obscure ownership, and relying on informal networks of support to protect assets. Despite the pervasive atmosphere of fear and persecution, these methods allowed some to shield their belongings from the relentless scrutiny of the state.

Another dark chapter in history is found in Nazi Germany’s policy of Aryanization, implemented between 1933 and 1945 under Adolf Hitler’s regime. Aryanization was designed to systematically transfer Jewish-owned businesses and property into the hands of “Aryan” citizens, stripping Jews of their economic power and wealth.

The Nazi government employed a range of tactics to facilitate this transfer, including legal decrees that forced the sale of Jewish assets at drastically reduced prices, as well as violent pogroms that terrorized Jewish communities and forced them to flee. In this environment of coercion and violence, many Jewish families sought to protect their assets by transferring funds and property abroad, hiding valuables, or arranging false ownership transfers to trusted non-Jewish individuals.

In the United States, the government’s confiscation of gold in 1933 offers a striking contrast to the more overtly ideological or ethnic-driven confiscations of the Soviet, Chinese, and Nazi regimes.

During the Great Depression, President Franklin D. Roosevelt implemented a series of policies aimed at stabilizing the economy, one of which was the forced conversion of privately held gold into paper currency. This measure was designed to combat deflation and restore public confidence in the banking system, but it also represented a significant intrusion into the personal property rights of American citizens.

Under Executive Order 6102, individuals were required to surrender their gold holdings to the government in exchange for paper money, with financial penalties or even imprisonment for those who failed to comply.

While many citizens adhered to the order, a number of individuals employed various tactics to avoid surrendering their gold. These included hoarding gold in hidden locations, exploiting legal loopholes that allowed for certain exemptions, storing gold in offshore accounts, and participating in black market trading or barter systems.

Each of these historical episodes of asset confiscation underscores the extremes to which governments will go in pursuit of political, economic, or ideological goals.

Whether driven by a need to consolidate political control, redistribute wealth to fulfill ideological aims, or stabilize an economy on the brink of collapse, the actions of these regimes resulted in profound social disruption, economic devastation, and widespread human suffering.

In each case, state intervention—through aggressive asset confiscation—deepened the divide between governments and their citizens, often intensifying resentment and leading to acts of defiance. The human toll was not limited to financial loss; entire communities were destabilized, livelihoods destroyed, and societal structures upended, all in the pursuit of these ambitious governmental agendas.

Yet, amid the harshness of these measures, these episodes also illuminate the extraordinary resilience and resourcefulness of individuals and communities determined to protect their assets and livelihoods. Faced with overwhelming odds and often brutal enforcement, people devised creative methods of resistance. From concealing valuable property and leveraging legal loopholes to forming clandestine networks and escaping oppressive regimes, these acts of defiance highlight a fundamental human instinct for survival.

The capacity to adapt and push back against overwhelming state control demonstrates a profound determination to retain autonomy, even under the most oppressive circumstances.

By reflecting on these historical events, we gain valuable insight into the delicate balance between state authority and individual property rights. These instances of asset confiscation expose the vulnerabilities of ownership during periods of political and economic instability, underscoring the precarious nature of personal wealth when confronted with unchecked governmental power.

More importantly, they serve as enduring reminders of humanity’s ability to resist, adapt, and reclaim autonomy in the face of overwhelming adversity. Ultimately, these episodes reinforce the critical importance of safeguarding individual rights and freedoms, even when faced with the seemingly invincible force of state intervention.

The Soviet Collectivization and Dekulakization (1929-1933)

In the late 1920s and early 1930s, the Soviet Union, under the iron-fisted rule of Joseph Stalin, embarked on a colossal and brutal campaign of collectivization. This policy was the cornerstone of Stalin’s First Five-Year Plan, designed to transform the Soviet Union from a predominantly agrarian society into an industrial powerhouse. The grand vision involved consolidating individual landholdings and labor into collective farms known as kolkhozes and state farms called sovkhozes. The ambitious goals were to boost agricultural productivity, generate surplus grain for export, and fund rapid industrialization.

Stalin’s ideology painted collectivization as essential to eliminating the Kulaks, the relatively wealthier peasants seen as class enemies obstructing socialist progress. To Stalin, the Kulaks represented a threat to his vision of a socialist utopia. They were perceived as hoarders and exploiters, resisting the equitable distribution of resources. Economically, the Soviet government aimed to extract grain surpluses from the countryside to support urban workers and finance industrial projects. Politically, the consolidation of land and labor into collective farms was a strategic move to exert greater control over the rural population and suppress any potential dissent. By breaking the economic independence of the peasants, Stalin aimed to solidify his control over the countryside.

The methods employed to enforce collectivization and dekulakization were multifaceted and often brutal. The government used a mix of coercion, propaganda, and outright violence. Forced collectivization involved peasants being coerced into surrendering their land, livestock, and equipment to join collective farms. State agents and party activists used threats and intimidation to persuade or force peasants into compliance. These activists, often young and ideologically driven, conducted aggressive campaigns in villages, sometimes going door-to-door to enforce policies.

Kulaks were specifically targeted as class enemies, facing expropriation, arrest, deportation, and even execution. The dekulakization campaign involved identifying, dispossessing, and removing kulaks from their communities in a process that was often arbitrary and brutal. Local officials had quotas to fulfill, leading to widespread abuses and targeting of anyone seen as a threat or simply unfortunate enough to own slightly more property than their neighbors.

The state also requisitioned grain and livestock from peasants, often leaving them with insufficient food and resources to survive. Grain procurement quotas were imposed, and failure to meet these quotas resulted in severe penalties, including the confiscation of all remaining food supplies. These quotas were often unrealistically high, putting immense pressure on peasants to meet demands at the cost of their survival.

Propaganda played a significant role in promoting collectivization, with the government depicting it as a path to prosperity and a socialist utopia. Posters, films, and speeches glorified collective farming and painted a rosy picture of a future where everyone shared in the bounties of the land. Agitation propaganda campaigns involved speeches, pamphlets, and posters aimed at convincing peasants of the benefits of collectivization. Schools and youth organizations were mobilized to spread the message, and dissenting voices were quickly silenced.

The impact on the peasantry was devastating.

Millions of peasants suffered from displacement, famine, and violence, fundamentally altering the social and economic fabric of rural communities. Many kulaks and their families were deported to remote areas such as Siberia and Kazakhstan, where they faced harsh conditions and high mortality rates.

These remote regions were often ill-prepared to receive large numbers of deportees, leading to widespread suffering and death. The requisitioning of grain and livestock led to widespread famine, most notably the Holodomor in Ukraine, where millions of people died of starvation. The Holodomor was a particularly harrowing tragedy, with entire villages wiped out and desperate survivors resorting to eating grass, bark, and, in some cases, even more desperate measures.

Resistance to collectivization was met with brutal repression, including mass arrests, executions, and punitive measures against entire villages. Villages that resisted were labeled as “enemy strongholds” and subjected to collective punishment. This often included increased grain quotas, confiscation of all food supplies, and the arrest of community leaders.

Despite severe repression, many peasants resisted collectivization and employed various strategies to avoid asset confiscation. Peasants hid their produce and livestock in secret caches or remote areas to prevent confiscation. Grain was buried in hidden pits, and livestock was sometimes driven into forests or remote areas to avoid requisition. Acts of sabotage, such as destroying machinery and livestock, were common.

This was a form of resistance intended to undermine the productivity of collective farms. Passive resistance tactics included working slowly, feigning ignorance, or intentionally mismanaging collective farm resources. Some peasants fled to urban areas, seeking jobs in factories and construction projects to escape collectivization. The migration to industrial centers increased as peasants sought to escape the oppressive conditions in the countryside.

Peasants also formed support networks to help each other hide assets and provide mutual aid. Secret meetings and communications were used to coordinate resistance efforts and share information about government actions. These networks provided a lifeline for many, offering support and solidarity in the face of overwhelming oppression.

The Holodomor, also known as the Terror-Famine, was one of the most tragic outcomes of Stalin’s collectivization policies. It occurred in Soviet Ukraine from 1932 to 1933, resulting from forced grain requisitions, unrealistic procurement quotas, and harsh punitive measures against those who resisted.

Estimates of the death toll range from 3.5 to 7 million people, with widespread starvation, disease, and death. Despite efforts to conceal the famine, reports from foreign journalists and diplomats brought international attention to the crisis, though the Soviet government denied the existence of the famine and suppressed information.

The Holodomor remains a deeply painful chapter in Ukrainian history and is widely regarded as a genocide orchestrated by the Soviet regime.

The long-term consequences of collectivization and dekulakization were profound and far-reaching. The upheaval in rural areas led to a significant decline in agricultural productivity, with collective farms often inefficient and poorly managed. The mass displacement and deaths of millions of peasants altered the demographic landscape of the Soviet Union.

The trauma of collectivization and the Holodomor left a legacy of mistrust towards the Soviet government, contributing to the eventual collapse of the Soviet Union.

Collectivization succeeded in extending the state’s control over the countryside but also entrenched fear and resentment among the rural population. The policies of collectivization and dekulakization did not achieve the intended economic benefits and instead left a legacy of suffering and inefficiency.

The Soviet collectivization and dekulakization campaigns represent one of the most significant and tragic episodes of state-imposed asset confiscation in history. The brutal methods employed by the government, combined with the resilience and ingenuity of the peasantry, highlight the complex dynamics of power, resistance, and survival. Understanding this period is crucial for comprehending the broader history of the Soviet Union and the enduring impact of Stalin’s policies on its people.

The resilience of the peasantry in the face of such brutal oppression underscores the human spirit’s capacity for resistance and survival against overwhelming odds.

The Chinese Cultural Revolution (1966-1976)

The Chinese Cultural Revolution, initiated by Mao Zedong in 1966, stands as one of the most tumultuous periods in modern Chinese history. This decade-long movement was characterized by widespread social, political, and economic upheaval. Mao’s goal was to enforce communism by removing capitalist, traditional, and cultural elements from Chinese society. This ambitious and ruthless campaign led to the persecution of millions and the confiscation of personal and communal assets on an unprecedented scale.

Mao, in his relentless drive to reshape China, called upon the nation’s youth. Imagine millions of young people, mostly students, mobilized to form the Red Guards. These enthusiastic, often fanatical, groups were tasked with attacking the “Four Olds”: old customs, culture, habits, and ideas. The Red Guards, fuelled by revolutionary fervor, would ransack homes, destroy cultural artifacts, and seize property.

These young revolutionaries, armed with Mao’s Little Red Book, stormed through cities and villages alike, determined to purge society of its capitalist and traditionalist elements. Streets that were once vibrant with the rhythm of daily life were now filled with the chaotic energy of the Red Guards. They scoured neighborhoods, hunting for any sign of the “Four Olds.” No item was too insignificant; anything from ancient family heirlooms to revered cultural relics became their targets.

Public struggle sessions became a chilling spectacle across China. Individuals identified as counterrevolutionaries, landlords, intellectuals, and others deemed bourgeois were subjected to public humiliation, beatings, and confiscation of their property. Imagine a crowded square where accused individuals were paraded before jeering crowds, forced to confess their “crimes” while enduring physical and verbal abuse.

These sessions were not mere public shaming; they were brutal, often violent displays of power meant to break the spirit of the accused and serve as a warning to others. Their homes and belongings were often seized by the state, leaving families destitute. The trauma of these public humiliations lingered long after the crowds dispersed, marking the psyche of an entire generation.

Those not caught up in struggle sessions might find themselves sent to rural labor camps for re-education. These camps, far from the cities, were places of hard labor and harsh conditions. Imagine being uprooted from urban life and thrust into the backbreaking work of the countryside. People were forced to toil in the fields or work on infrastructure projects, all while being indoctrinated with revolutionary ideology. Life in these camps was gruelling; the combination of physical exhaustion and ideological brainwashing wore down even the most resilient spirits. Their properties were confiscated and redistributed by the state, further dismantling the old social order and creating a new class of disenfranchised citizens.

The impact on society was devastating.

Millions faced persecution, with estimates suggesting up to 1.5 million people were killed and countless others imprisoned, tortured, or displaced. Families were torn apart, and communities shattered as neighbors turned against each other, driven by fear and ideological fervor. The economy suffered as well, as intellectuals and skilled workers were removed from their positions, and resources were diverted to support revolutionary activities. Factories slowed, agricultural production dropped, and the nation struggled to maintain even basic economic stability. The economic infrastructure that had been painstakingly built over decades crumbled under the weight of ideological purges and mismanagement.

The Cultural Revolution also targeted China’s rich cultural heritage. Libraries, temples, and monuments were destroyed. Books, paintings, and other cultural artifacts were burned or otherwise eradicated. Picture centuries-old temples reduced to rubble, rare manuscripts turned to ash, and priceless artworks lost forever.

The aim was to break with the past and create a new, ideologically pure culture, but the result was an irreplaceable loss of historical and cultural treasures. The destruction was not just physical; it was an attempt to erase the very memory of China’s rich and diverse heritage. The emptiness left by this cultural annihilation was felt deeply by those who understood the value of what was lost.

Despite the atmosphere of fear and repression, many Chinese citizens found ways to resist and protect their assets. People hid valuable items such as jewelry, family heirlooms, and important documents in clever places—buried underground, concealed in walls, or tucked away in hollowed-out furniture. These acts of defiance were often small but significant, providing a lifeline to a past that many were desperate to preserve. Families altered or destroyed official documents to obscure their backgrounds or ownership of property, all in a bid to avoid persecution.

Communities formed clandestine networks to help each other hide assets, provide false testimonies, or even escape to safer areas. Imagine neighbors collaborating to protect a targeted family by hiding their possessions and spreading misinformation about their activities. These networks operated in the shadows, providing a fragile but crucial support system for those targeted by the revolution. Some people outwardly conformed to the demands of the Red Guards while secretly maintaining their old customs and traditions. These acts of defiance, though small, were acts of bravery in a time of widespread terror. In the face of overwhelming oppression, these quiet acts of resistance were a beacon of hope.

The long-term consequences of the Cultural Revolution were profound.

The destruction of cultural artifacts, historical sites, and intellectual works resulted in an irreparable loss to China’s cultural heritage. The persecution and violence left deep psychological scars on survivors and their families, affecting subsequent generations. The memories of the brutality, the fear, and the loss were passed down, creating a legacy of trauma that would influence Chinese society for decades to come. And disruption of the education system created a generation with gaps in their formal education, further hindering the nation’s progress.

Economically, the upheaval led to stagnation. The persecution of skilled workers and intellectuals hindered technological and industrial progress. Factories and farms, once bustling with activity, were now inefficient and unproductive, unable to meet the demands of the population. The forced redistribution of property and assets, while intended to eliminate class distinctions, often resulted in inefficiencies and further economic disruption. The grand vision of a classless, perfectly equal society clashed with the harsh reality of economic decline and social chaos. The economy was left in tatters, struggling to recover from the damage inflicted during the revolution.

In the end, the Chinese Cultural Revolution serves as a poignant reminder of the devastating impact of ideological extremism and political purges on a society.

Through the detailed examination of government actions and public resistance, we gain a deeper understanding of this historical period. The strategies employed by ordinary people to protect their assets and survive highlight the resilience and ingenuity of the human spirit. These stories of survival and resistance are a testament to the strength and courage of those who lived through this dark chapter in history. As China continues to navigate its complex historical legacy, the lessons of the Cultural Revolution remain relevant for understanding the interplay between state power and individual rights.

The Confiscation of Gold by the United States Government (1933)

The onset of the Great Depression in 1929 plunged the United States into a severe economic crisis unparalleled in its history. The stock market crash not only shattered the financial system but also led to catastrophic levels of unemployment, countless bankruptcies, and widespread despair. As banks collapsed and businesses shuttered, the American public grappled with unprecedented hardship.

By 1933, the economic situation had grown even more dire, with no sector of the economy untouched. Into this bleak landscape stepped Franklin D. Roosevelt, inaugurated as President in March of that year, bringing with him a new vision aimed at rescuing the nation from its economic plight.

Roosevelt’s New Deal was a series of programs and policies designed to revive the economy and restore confidence among the American people.

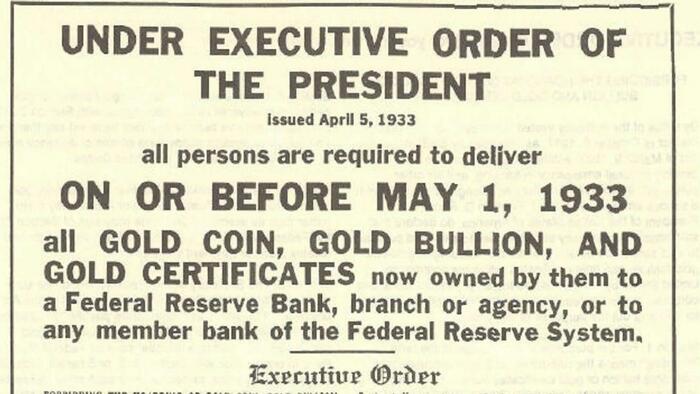

Among these initiatives, the decision to confiscate gold under Executive Order 6102 in April 1933 stands out as particularly bold and contentious.

This executive order mandated that all persons, businesses, and institutions within the United States surrender their gold coins, bullion, and certificates to the Federal Reserve, receiving in return paper currency valued at $20.67 per troy ounce.

Roosevelt’s rationale for such a drastic measure was rooted in the belief that hoarding gold was exacerbating the economic downturn. By hoarding gold, he believed that individuals were limiting the money supply available, which in turn deepened the deflation that was strangling economic growth.

The move to confiscate gold was aimed directly at undermining the gold standard, a monetary system in which the value of national currencies was directly linked to specific amounts of gold. This standard restricted the Federal Reserve’s ability to increase the money supply during economic downturns, thereby limiting its ability to stimulate economic activity. By removing gold from private hands and centralizing it within the Federal Reserve, Roosevelt hoped to expand the money supply and thus combat the crippling deflation.

The following year, Roosevelt pushed forward with the Gold Reserve Act of 1934, which not only reaffirmed the government’s control over all gold but also increased the official price of gold from $20.67 to $35 per ounce. This significant devaluation of the dollar sought to boost economic recovery by making American goods cheaper on the international market, thus increasing exports and reducing the balance of trade deficit. The government enforced these new policies with stringent penalties, threatening violators with hefty fines and imprisonment, signaling a stern commitment to these drastic measures

Public reactions to these gold policies were deeply divided. While many Americans complied with the order, either out of a sense of national duty or resignation to the economic emergency, a significant number resisted, driven by a combination of distrust in the government and a determination to safeguard personal wealth.

Resistance took many forms. Individuals went to great lengths to hide their gold, employing creative methods to evade confiscation. Gold was buried in backyards, secreted away in hidden compartments of homes, or transformed into innocuous items like jewelry or art.

Others exploited loopholes in the legislation, particularly the exemptions that allowed professionals like dentists, jewelers, and artists to retain necessary gold for their work. Some claimed these professional exemptions under dubious pretenses, while others rushed to invest in numismatic coins—rare and collectible coins that were initially exempt from confiscation.

The affluent and certain businesses looked beyond American borders, moving their gold assets to international banks or engaging in elaborate foreign transactions to protect their holdings. As government scrutiny intensified, a black market for gold flourished, allowing covert trading and providing an avenue for transactions that circumvented official channels. In certain areas, barter systems emerged where gold acted as a medium of exchange, further undermining the government’s attempts to control the currency.

The long-term consequences of Roosevelt’s gold policies were profound and multi-faceted.

Economically, these measures provided the necessary liquidity to tackle deflation, facilitating a gradual recovery from the Depression. The increased money supply resulting from the devaluation of the dollar and the abandonment of the gold standard allowed for greater flexibility in monetary policy. This adaptability was crucial not only during the remaining years of the Depression but also in shaping the economic strategies of subsequent decades.

The revaluation of gold and the shift away from a strict gold standard also laid the groundwork for the Bretton Woods system, which established the U.S. dollar as the backbone of the international financial system after World War II. This system played a pivotal role in global economic stabilization until its dissolution in the early 1970s.

Culturally, the legacy of the gold confiscation left an indelible mark on American society, engendering a deep-seated skepticism toward government intervention in personal financial matters. This skepticism fostered a strong libertarian streak in some segments of the population, influencing American attitudes toward economic policy and investment in precious metals for decades.

The episode remains a potent symbol in discussions about government overreach and economic liberty, shaping the ideological debates that continue to influence American political and economic thought.

In retrospect, the U.S. government’s intervention in the gold market during the Great Depression was a watershed moment with lasting impacts. While it played a crucial role in addressing the immediate economic crisis and reshaping U.S. monetary policy, it also left a legacy of wariness about government power over personal assets.

These actions and their repercussions continue to echo through the financial markets and shape government policies, reminding us of the delicate balance between necessary economic intervention and the protection of individual freedoms.

Continue reading at the Macro Alchemist.

Loading…

Read the full article here