Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

An international research team has for the first time imaged and controlled a type of magnetic flow called altermagnetism, which physicists say could be used to develop faster and more reliable electronic devices.

A groundbreaking experiment at a powerful X-ray microscope in Sweden provides direct proof of the existence of altermagnetism, according to a paper published in Nature on Wednesday. Altermagnetic materials can sustain magnetic activity without themselves being magnetic.

The team from the UK’s Nottingham university that led the research said the discovery has revolutionary potential for the electronics industry.

“Altermagnets have the potential to lead to a thousand-fold increase in the speed of microelectronic components and digital memory, while being more robust and energy-efficient,” said senior author Peter Wadley, Royal Society research fellow at Nottingham.

Hard disks and other components underpinning the modern computers industry process data in ferromagnetic materials, whose intrinsic magnetism limits their speed and packing density. Using altermagnetic materials will allow current to flow in non-magnetic products.

“The most straightforward application of altermagnetism is to replicate the building blocks of current memory devices,” Wadley said. “Using altermagnets as replacements should lead to much faster, more efficient and more sustainable technology.”

A material’s magnetic properties depend on the spin of its electrons. In ferromagnetic materials such as iron, which respond strongly to magnetic fields, the electrons all spin in parallel with their neighbours. In antiferromagnetism, the other established type of magnetism, adjacent electrons spin in opposite directions and therefore cancel each other out, so the material as a whole does not respond to an external field.

In altermagnetic materials the electron spins are also antiparallel but the atoms and their accompanying electrons are rotated in an unusual way within the crystal structure. Such “magnetism with a twist” delivers useful properties, Wadley said.

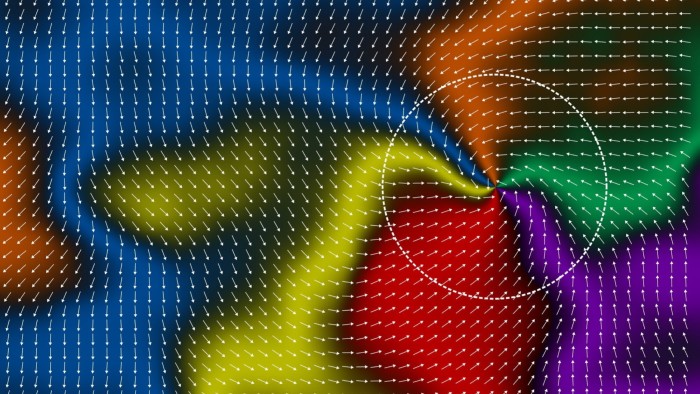

Images from the X-ray probe in the Max IV Laboratory in Lund, southern Sweden, show currents swirling in various directions within thin crystals of a manganese telluride semiconductor, as an external magnetic field was applied. The researchers created magnetic vortices that might be used for information storage and processing.

Physicists detected hints of a new magnetic phenomenon around 2020 and the term altermagnetism was first used in 2022.

“Our latest breakthrough makes altermagnetism a reality,” said Wadley. “We use microscopy to see the magnetic order in unprecedented detail. We can measure and control these properties in ways no other magnetic system allows.”

Claire Donnelly, group leader at the Max Planck Institute for Chemical Physics of Solids in Dresden, who was not involved in the research, called it “a really big step towards seeing the reality of altermagnetism and how we might be able to use it for future devices.”

Wadley said 200 scientific papers about altermagnetism have been posted in the past year. “This is not a flash in the pan,” he said. “It’s the beginning of something really important.”

“We need to find a candidate altermagnetic material and an industrial-scale way of processing it,” Wadley added. “It is not unrealistic to suggest that it could be 10 years away from application in electronics.”

Manganese telluride is not probably not suitable for industrial applications, though another altermagnetic semiconductor, chromium antimonide, might be. Physicists predict that more than 100 compounds will exhibit altermagnetic behaviour.

Scientists are mobilising to attract funding for research into altermagnetism on a larger scale, perhaps with industrial participation — though the patent position on the technology is uncertain, Wadley said.

Donnelly is cautiously optimistic about the prospects for altermagnetism’s practical applications. “If the predictions come true, I can imagine this having quite a large impact on society,” she said.

Read the full article here