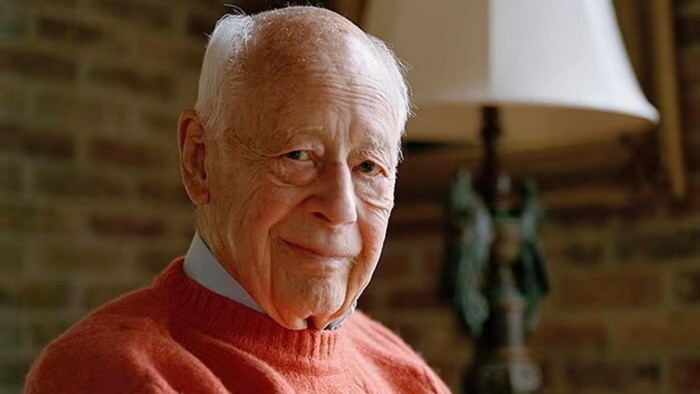

Author, thinker and public speaker Charles Handy, who died on Friday, aged 92, was one of the few non-Americans to merit the description “management guru”.

It was a term he disliked, preferring the tag “social philosopher”. Handy favoured counselling over consulting for leaders and his chosen method was “Socratic dialogue”. It often took place over a meal at one of his homes in Putney or Norfolk, to which he and his wife Elizabeth invited interesting thinkers, writers and business people.

But Handy’s many insights into organisations, offered in public lectures and a series of books and articles, were practical, prescient and often provocative.

In the 1980s and 1990s, he predicted now commonplace innovations in the world of work such as the rise of what would today be called the “gig economy”, the spread of outsourcing, and the growth of the portfolio career. Well into old age, he remained a bold, common sense advocate of human values in companies and a forthright critic of the dangers of breakneck automation. “If the organisation were purely digitised,” he said in a speech in 2017, “it would be a very dreary place, a prison for the human soul.”

Handy was born in County Kildare, in what is now the Republic of Ireland, son of a Protestant archdeacon. He described himself as “one of the last of the Anglo-Irish”, and had the right to both Irish and UK passports. “Our beginnings do shape our ends,” he wrote in the autobiographical Myself And Other More Important Matters in 2006. “I can feel Irish at heart but still belong physically and emotionally to Britain and, indeed, to Europe.”

He read “Greats” at Oriel College, Oxford — a mixture of classics, history and philosophy — adding a foundation of ancient thought to his work. A central concept, from Aristotle, was the quest for eudaemonia, or fulfilment, which Handy interpreted as “doing the best at what you’re best at”.

Handy joined Shell International as a marketing executive at a time when the company represented the acme of postwar managerial best practice. It was his only experience of working as a corporate employee and fed a deepening pool of personal stories that he later shaped, distilled and used to dramatic effect in his books, lectures and broadcasts.

In the 1960s and 1970s, Handy was a pioneer of British business education, bringing the relatively novel idea of executive education back from a stint at MIT’s Sloan School of Management to London Business School, where he taught a version of the US programme.

In 1981, though, he took the leap into what he would later call the “portfolio life”. He stepped off the education treadmill and went freelance. The change of direction gave him the time and freedom to write a series of books on modern organisations, including The Age of Unreason (1989) and The Empty Raincoat (The Age of Paradox in its US version) (1994), in which he tackled the paradoxes and challenges of economic progress and the changing workplace. The transition also entailed what he later described as a rewriting of his “marriage contract” with Liz. She resumed her career as a photographer and — compensating for Handy’s initial reluctance to charge a speaker fee — became his business manager, agent and image consultant.

Handy’s lucid, conversational prose was characterised by the use of vivid metaphors. These included the “shamrock organisation”, an early description of a company’s network of staff, contractors and part-timers, and “the elephant and the flea”, his image for the symbiotic relationship between large multinationals and independent workers, drawn from his 2001 book of the same name.

In The Second Curve (2015), Handy replayed some of his greatest hits but it was also full of radical proposals for change in areas as different as measuring the economy and organising British democracy. He also wrote how he had resolved as he grew older to “remain interesting to the generation below me, be it by wit or wisdom, occasionally seasoned with some judicious generosity”. He and Liz, who died in a car accident in 2018, lived up to that resolution.

Handy also remained a genial but wily marketer of his brand. Asked in 2015 by one admirer to offer an endorsement for a new book, Handy emailed back “I never do blurbs” but added that he was happy to write a foreword — the sort of “judicious generosity” that also ensured his name appeared on the front cover.

His determination to disseminate his ideas continued to shine through even after a stroke in 2019. Impatient with the strictures of hospital, he persuaded nurses to pin a note above his bed reading “Charles Handy Is Allowed To Do Whatever He Wants To Do”, and laid plans to write about his experience.

He died peacefully at home, surrounded by family. He leaves behind two children, Scott and Kate, and four teenage grandchildren, to whom he dedicated his 2020 book 21 Letters on Life and Its Challenges.

He continued to do the best at what he was best at until the end. A final book, The View from Ninety: Reflections on Living a Long, Contented Life, will appear next year.

In 2017, Handy gave the closing speech at the Global Peter Drucker Forum, a conference in honour of another reluctant management guru whose work he admired. He closed with a rallying cry for a management revolution. “Let us start small fires in the darkness until they spread and the whole world is alight with a better vision of what we could do with our businesses,” he declared to a standing ovation.

Read the full article here