Good afternoon, I’m Laura Hughes. One of the areas I cover for the FT is the NHS and this week we learned more about the government’s strategy for bringing down the eye-wateringly high waiting lists across hospitals in England.

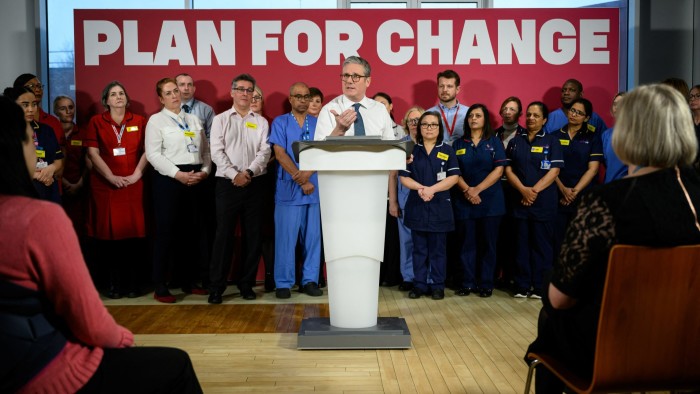

Reducing the backlog has become such a cornerstone of how this administration expects to be held accountable by the public at the next election that it was no surprise to see the prime minister take to the podium on Monday and unveil a series of proposals to tackle the delays.

In reality, the main pillars of Sir Keir Starmer’s plan were more about extending current work set in motion by the last Conservative administration than anything radically new.

Under the plans, the NHS in England will be given the capacity to perform more tests and checks through the creation of additional one-stop shop community diagnostic centres (CDCs), to which patients will be referred by doctors for scans and other investigations.

The number of surgical hubs, which are also not a new phenomenon, will be expanded. Starmer said the NHS would create 14 surgical hubs within existing hospitals focused on less complex procedures such as joint replacements and cataract surgery.

The government believes these measures will help to create an additional 450,000 appointments each year.

More diagnostic equipment is badly needed in the NHS, which has fewer scanners and other facilities than many comparable OECD countries, so this was of course welcome news.

The elephant in the room

But after the dust settled and the plans were pored over by embattled NHS staff and policy experts, the elephant in the room began to rear its uneasy head: who is going to actually staff these new hubs.

My colleague Amy Borrett looked at the latest data available from NHS England for last year, which shows there are still 107,900 NHS vacancies in England. This includes 31,800 vacancies in registered nursing.

The good news is that overall vacancies are down on their peak and lower than the same period pre-pandemic. The total NHS vacancy rate in England was 7.3 per cent at the end of the third quarter 2024, down from 8.4 per cent the year before, but it still begs the question of how the NHS is going to fulfil ministers’ promises to create these extra services.

As one hospital boss tells me: “Even if we receive an increase in funding, we do not have the staff to increase opening hours. At the moment we are being told to cut back staffing numbers rather than increase them.”

That boss also criticised what they described as a “lack of joined up strategy for the delivery of the CDCs and surgical hubs”, adding: “Many of them are far too small to make a difference.” This chief executive believes the government should be looking more at subregional centres, which can deliver at scale.

Setting up and running new CDCs and surgical hubs is not straightforward and comes with “major logistical and staffing considerations”, says Dr Billy Palmer, a senior fellow at the Nuffield Trust think-tank.

“While NHS staff numbers have risen, chronic shortages remain in many specialties and parts of the country, which could well thwart the government’s promised rise in appointments.”

He also makes the point that adequate staffing is just as crucial where independent providers are brought in to set up new centres and hubs, as the NHS and private providers are “largely pulling on the same pool of staff”.

Expanding access to the centres is a critical part of the government’s ambition to reduce the number of people waiting for NHS treatment, which stands at 7.48mn in England, according to NHS England data published earlier today.

Both Starmer and the health secretary Wes Streeting have promised that by the end of this parliament 92 per cent of patients would begin treatment for an ailment or get the all-clear within 18 weeks.

This target is currently met for just 59 per cent of patients in England. On Monday the government set a new interim target of 65 per cent to be met by March next year.

Leaning on the private sector

Starmer also announced that a “new agreement” had been signed to expand the existing relationship between the NHS and private health providers, designed to encourage the independent sector to utilise excess capacity and help reduce the waiting list.

How much extra elective care is required to meet the government’s 18-week ambition depends on how quickly new referrals for treatment grow, says Charles Tallack, director of research and analysis at the Health Foundation.

The growth in referrals is currently running at an annual rate of 1.5 per cent, he points out. Before the pandemic, it was 2 per cent.

“If this lower referral growth continues, we estimate that elective care needs to grow by around 2.4 per cent a year to achieve the 18-week ambition by the end of the parliament.”

Whether there will be sufficient staff to deliver on the government’s ambitions depends partly on how much productivity improves, Tallack argues.

Analysis by the Health Foundation reveals that elective care hubs show some promise in this area, with hospitals that have them achieving activity increases of more than 20 per cent. “Our study doesn’t look at whether this was achieved with the same number of staff,” Tallack notes.

“Crucially, this depends on getting the combination of specialist staff that is required right and understanding where they are needed most.”

The thorny issue of staff shortages is not going to go away, nor are the increasing demands from an ageing and growing population on the health service.

Are you enjoying The State of Britain newsletter? Sign up here to get it delivered straight to your inbox every Thursday. Do tell us what you think; we love hearing from you: [email protected]

For more economics coverage sign up to our new Sunday edition of Free Lunch with Tej Parikh, an editorial writer.

Britain in numbers

This week’s chart spotlights the extraordinary pressure being put on the finances of England’s school system as a result of a doubling in demand for special educational needs and disabilities (Send) provision over the past decade, writes Peter Foster.

As the Institute for Fiscal Studies set out in its annual report on education spending this week, spending on Send is gobbling up a large chunk of the relatively generous funding settlement granted to the Education department at last October’s Budget.

Add in the cost of funding the 5.5 per cent teachers’ pay increase and larger contributions to teachers’ pensions and most headteachers are going to find themselves looking for cuts, even though the government will (rightly) say budgets are going up in cash terms.

The challenge, as the IFS’s Luke Sibieta tells me, is that even if Labour follows through on its commitment to reform a system that is financially unsustainable, this will cost money — billions of pounds, potentially — because you have to meet current needs while simultaneously investing in future improvements.

This is an immensely politically sensitive topic, but the brutal truth is that the system set up by David Cameron’s government in 2014 has created what one senior Labour official calls a “blank cheque” for parents that the government has simply not resourced.

The system has been funded by allowing councils a so-called “statutory override”, which allows them not to count Send spending when they balance their books. The result is that according to official figures councils will face cumulative financial deficits of up to £4.9bn by March 2026 when this temporary fix expires.

As Sibieta observes, this is a “ridiculous way of planning public spending”, because it is obvious to everyone that the override is going to have to continue in some way or a large number of councils will go bankrupt.

The government knows this, but taking away existing entitlements from people — particularly those with special needs — is politically risky.

For now, the government has committed £740mn to improve the Send offer in mainstream schools in the hope it will cut the number of parents seeking so-called education, health and care (EHC) plans that legally entitle them to support.

But as one official told my colleague Anna Gross before Christmas, reforms are coming that “would mean thousands fewer pupils getting [EHC] statements.” Labour likes to talk about “tough choices”. This, if it truly dares, will be one of them.

Data visualisation by Amy Borrett

The State of Britain is edited by Gordon Smith. Premium subscribers can sign up here to have it delivered straight to their inbox every Thursday afternoon. Or you can take out a Premium subscription here. Read earlier editions of the newsletter here.

Read the full article here