Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the Climate change myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

The writer is a science commentator

As parts of southern California continue to burn in what could be the costliest disaster in American history, it feels odd to recall the record-breaking rainfall and snow that characterised the region’s previous two winters.

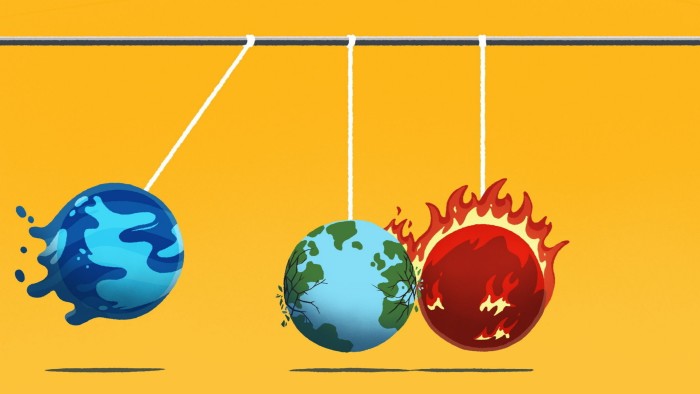

But even though wildfires and floods seem like meteorological opposites, they appear to be two sides of the same climate coin. Scientists suggest the two extremes could be related through a phenomenon known as “hydroclimate whiplash”, defined by volatile swings between very wet and very dry conditions — with climate change intensifying this.

Heavy rainfall boosts plant growth, nurturing vegetation that turns into tinder during the longer dry season. The cycle of sudden deluge and extended drought becomes a destructive see-saw of irrigation and ignition, bringing flash floods, landslides and wildfire. Instead of treating flood and fire as separate phenomena, we should be joining the soaked and charred dots to recognise and mitigate the dual risks of this whiplash effect. It is also more evidence, if more were needed, that limiting global temperature rise matters for a liveable future.

The atmosphere acts like a sponge, able to both soak up and release moisture. Thanks to fundamental thermodynamics, a hotter atmosphere is thirstier and able to contain more water vapour; for every degree Celsius that the atmosphere warms, it can evaporate, absorb and release 7 per cent more water. This allows more moisture to be drawn out of plants and soil, exacerbating drought conditions. And what goes up must eventually come down.

“The problem is that the [atmospheric] sponge grows exponentially, like compound interest in a bank,” explained Daniel Swain, a climate scientist at the University of California Los Angeles, who teamed up with other researchers to look at the transitions between very wet and very dry weather since the 1950s.

While their study, published in Nature Reviews Earth & Environment, recognises the challenge of defining and measuring such volatility, they conclude that whiplash has increased by between 31 and 66 per cent since the mid-20th century. Swain warns of worse to come: “The evidence shows that hydroclimate whiplash has already increased due to global warming, and further warming will bring about even larger increases.” The global regions most at risk include central and northern Africa, the Middle East and south Asia — heavily populated areas with modest economic resources.

Though extreme rainfall and drought are each grim enough on their own, sharp switching between the two is especially unwelcome. It compromises water quality through polluted run-off and algal blooms; it damages crops and grazing land; it destroys housing and infrastructure. It threatens human health in other ways, through waterborne diseases and surging rodent and mosquito populations. Transitions from very wet to very dry allow flammable vegetation to grow abundantly and then dry out. It is not so much boom-and-bust as bloom-and-combust.

Perhaps the study’s starkest message is that this disruptive yo-yoing, the researchers write, is “likely to challenge not only water and flood management infrastructure, but also disaster management, emergency response and public health systems that are designed for 20th-century extremes”. Keeping reservoirs full seems intuitively sensible to guard against drought — but sudden, heavy rains can cause them to overflow, causing flooding. The focus should shift away from single hazards to “the potential impact of compounding extremes”, the team adds.

Possible solutions include expanding and joining up floodplains, to disperse floodwater over a greater area and top up groundwater levels to lessen drought risk; using detailed meteorological forecasts to manage reservoirs; and promoting “sponge cities”, with permeable features like parks and lakes that absorb and filter downpours, rather than concrete-heavy surfaces that contribute to flash flooding.

Arson, building regulations and seasonal winds all contributed to the disaster in California, but it is increasingly untenable to claim that anthropogenic climate change plays no part in the historic weather events that have become the norm this century.

Each historic event, meanwhile, is composed of multiple human miseries: in this case, neighbourhoods reduced to ashes; undrinkable water; unbreathable air; uninsurable housing, and mercenary rents for the homes that remain. Los Angeles, home of the fake Hollywood dystopia, is showing us what it looks like for real.

Read the full article here