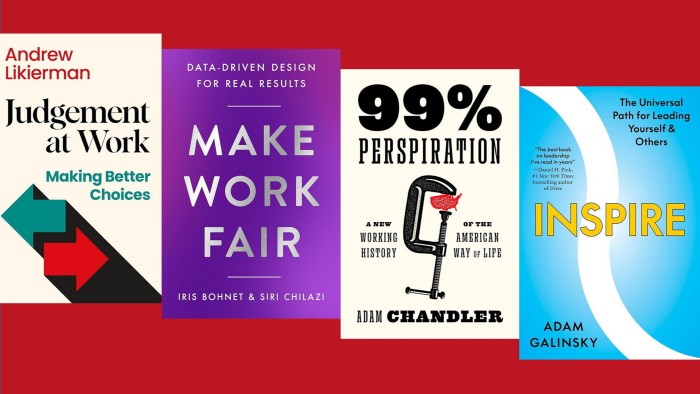

‘Make Work Fair: Data-Driven Design for Real Results’, by Iris Bohnet and Siri Chilazi

At a time when diversity, equity and inclusion programmes are under fire, Harvard-based gender equality experts Bohnet and Chilazi offer a wealth of practical, evidence-based approaches to help ensure fairness at work. If DEI is “ripe for a rethink”, as both the authors and recent energy-sapping culture wars suggest, “fairness” might be an acceptable replacement term. “Very few people are against fairness”, even if “we don’t all agree on what it entails”.

Bohnet and Chilazi’s definition is: “True equal access and opportunity to thrive.” Their data-driven paths to fairness include clever behavioural tricks and more ambitious organisational programmes. In the first category comes a workaround for CV gaps that trip up those candidates, often women, who have taken career breaks. A study shows that simply listing work experience by years worked, without dates, increases the likelihood of interview by 15 per cent. In the latter category is a strong call for paid, gender-neutral, non-transferable parental leave. All ideas are underpinned by abundant references to their own and others’ research.

Bohnet’s first book, What Works, made the final of the FT’s 2016 business book award with its simple, behavioural science-based alternatives to ineffective diversity training programmes. Make Work Fair is a timely guide to the latest research, aimed, the authors write, at “the activist working to advance DEI — as well as the activist working to limit DEI”. Andrew Hill

‘99% Perspiration: A New Working History of the American Way of Life’, by Adam Chandler

Chandler’s book is the history of an idea and the damage it has wrought in American life. The title references a quote from inventor Thomas Edison, who is supposed to have said that genius is “1 per cent inspiration and 99 per cent perspiration”. But Chandler challenges the notion that hard work always pays off and that individuals determine their fate through their own effort. He dubs the thinking behind Edison’s credo “American Abracadabra”, a myth that is “part Rosebud, part Excalibur, part Sisyphus and part ‘Free Bird’”.

The first part of the book examines how Americans grew to fetishise work, and how myth often belies historical fact. Chandler writes, for example, that one reason so many white Americans balk at acknowledging the far-reaching impact of slavery is because it grotesquely exposes how the myth of hard work paying off is contradicted by reality.

Chandler explores the dark fruits of the obsession with self-made success in the second part of the book, identifying it as at least a partial cause of contemporary overwork, division, isolation and more. Occasionally it feels as if, to borrow a work-related aphorism, he has a hammer and is hunting for nails.

So be it. A book seeking to reframe a way of thinking that deeply shapes American psyches, lives and society must argue aggressively, and Chandler’s intervention offers much to consider. Claire Bushey

‘Judgement at Work: Making Better Choices,’ by Andrew Likierman

A former dean of London Business School, director of the Bank of England, and member of boards from Germany to the US, Likierman has taken plenty of decisions. But although there is a wide literature on decision-making, few books examine the critical element of judgment.

What is judgment exactly? Likierman defines it as combining relevant knowledge and experience with personal qualities to form opinions or make decisions. He argues we shouldn’t be dissuaded by judgment being “difficult to pin down”: we can get better at it, using a neat framework that begins with experience, awareness and trust, through feelings and beliefs, choice and finally delivery.

Likierman appeals to a rich range of examples of good, or poor, judgment. He describes how professionals in areas from medicine to law exercise judgment by noticing details, listening to individuals and understanding culture. Speed, managing uncertainty and taking into account gut feelings are also part of it, as is avoiding “complacency, overconfidence, or habit”.

This is a book grounded in both theory and philosophical questions related to judgment. But it is also a practical guide, devoting much to applying judgment in business situations, with an accessible and fun section including quizzes and activities for putting ideas into action. Bethan Staton

Inspire: The Universal Path for Leading Yourself and Others, by Adam Galinsky

This book begins with accounts of two terrible crises. In the first, the pilot of Southwest Airlines Flight 1380 reassures passengers that their plane is not going down, guiding it to land after its left engine exploded — a success she puts down to an informal conversation with her crew before departure. In the second, the captain of the Costa Concordia ship abandons his vessel as it sinks, a dereliction of duty for which he is later imprisoned for 16 years.

The very different outcomes highlight opposing examples of leadership on what Galinsky describes as an “enduring continuum” — between inspiring and infuriating.

Drawing on years as a Columbia Business School professor, Galinsky digs into how leaders can become more self-aware about the impact their words and actions have on others — however insignificant or small they might seem. Silence, for example, can be infuriating. Ever dropped an employee an email saying you want to speak to them without saying why? They may be filling the void with worst-case scenarios.

“Awareness that our behavior may be sending unintended signals can help us install daily hacks to prevent panicking others,” Galinsky says, as he offers a “scientific pathway for staying on the inspiring end of the continuum”. His principles offer a meaningful blueprint for tackling business challenges — from producing innovative ideas to allocating scarce resources. Janina Conboye

‘Mindmasters: The Data-Driven Science of Predicting and Changing Human Behaviour’, by Sandra Matz

A computer with access to several hundred of your social media “likes” might know you better than your spouse. In a world where we have become accustomed to trading troves of personal data for bespoke technological experience, Mindmasters explores how digital footprints are decrypted and leveraged for profit — and how we might take back control.

Matz, an early researcher into psychological targeting, engagingly unpicks how companies translate our online activity into unique baskets of psychological traits, then use them to market their products. From Netflix’s recommendation algorithm to Cambridge Analytica, Matz explains how personality prediction has become a central part of our digital landscape, a trend that will probably be entrenched by artificial intelligence.

Refreshingly, though, Matz’s book isn’t all doom and gloom. She also highlights how nosy algorithms could be helpful with the right direction, from spotting early signs of degenerative disease to helping vulnerable people take control of their finances.

Matz returns repeatedly to the analogy of the small village where she was raised in Germany. The metaphor of snooping rural neighbours, although arguably overused, is vivid. There are also interesting examples and quizzes, including lists of terms used in Facebook status updates that are associated with personality traits. The word “sooooooo” predicts a high level of extroversion, for example. Stephanie Stacey

Read the full article here