Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

All is not well in the world of official economic statistics. In the UK, the ONS is under fire for faulty data while scaling back its outputs to deal with real-term budget cuts. Across the Atlantic, key US economic figures remain at risk from the Doge cuts unleashed by Elon Musk. And to cap it all, Diane Coyle’s latest book suggests that in recording the most fundamental data of all — GDP — we might well have been measuring the wrong thing for decades.

Of course Coyle is not the first economist to have expressed displeasure with GDP as the default international measure of progress, nor to have sought alternatives to it. Bhutan first published its measure of Gross National Happiness back in 2008. The following year, the Stiglitz-Sen-Fitoussi European Commission report provided some recommendations for moving beyond GDP to a broader set of indicators.

However, with early career experience at the UK Treasury and in journalism followed by long stints in academia and economic consulting, Coyle — the Bennett professor of public policy at the University of Cambridge and a co-founder of the Bennett Institute — is certainly well placed to make an argument that needs to win over both economists and politicians.

The Measure of Progress works well as a standalone read, but followers of Coyle’s work will spot that this is an evolution of her previous writings on GDP. Despite the sentimental adjective, 2014’s GDP: A Brief but Affectionate History concluded the measure was increasingly inappropriate for 21st-century economies no longer dominated by manufacturing.

And in her 2017 Indigo Prize-winning essay, written with Benjamin Mitra-Kahn, Coyle went so far as to propose a potential GDP replacement, in the form of a dashboard covering a range of natural, physical, human and social capital indicators as well as more intangible items such as intellectual property.

Here, Coyle builds her case further amid global disruptions including generative AI, cloud computing, “enshittification”, economic discontent, geopolitical tensions and the continuing impacts of climate change. Collectively, she argues, these all further undermine the credibility of GDP, part of a system of national accounts conceived in the 1940s and predicated on physical capital and limitless natural resources.

The first part of the book covers a systematic explanation of why GDP has run its course. Introductory chapters cover the move of advanced economies to the service sector and disintermediation created by “free” digital services. Time, and its relationship with technology, is a recurring theme.

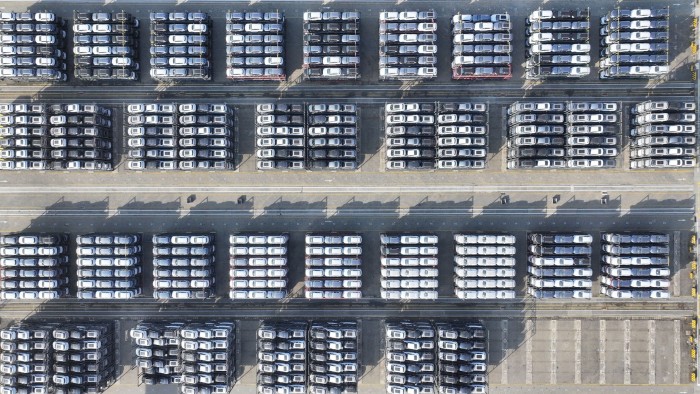

Coyle describes cross-border production networks of items such as smartphones to help highlight “yawning” gaps in official data: “the invisibility of the economy as it is now in the statistics available is extraordinary”. She points out that data flows across borders are not measured at all.

A chapter on “value” focuses on unpicking the merits or otherwise of price indices, leading to some tricky questions: “do we need price indices for (mainly) unpriced internet services?” This leads to a discussion of the components of wealth with the goal of introducing a new framework for measuring economic progress. In this final chapter, Coyle steps back slightly, its title (“A New Framework?”) featuring a very deliberate question mark.

Nevertheless, Coyle discounts moving to personal wellbeing (“not a very useful metric for policy at an aggregate level”), along with alternative indices which “internalise trade-offs”. She also discounts, for now, her own previous suggestion of deploying dashboards given the “psychology of processing information and presenting it”. Instead, among several options, Coyle proposes a comprehensive wealth framework, in effect a balance sheet of assets and the flows of services they provide.

She finishes in an upbeat mood about the power of statistical innovation to bridge the gap: new data sources allied to new methods that provide better descriptors of economic progress.

But her observation that many governments are cutting statistical office budgets at a time of great development need sounds a cautionary note for the consequences of inaction: “the more AI reshapes business and daily life, the more glaring the gap between the actual economy and official economic statistics will be.”

The real value of The Measure of Progress lies in its timing. Coyle reflects that while writing it economists, following the effects of the pandemic and Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, were preoccupied with productivity and inflation respectively. Scrutinising GDP of course fits in well with this agenda.

However, by the time of the book’s publication, global centre stage had been taken by a new trade war sparked by Donald Trump’s tariff announcements aimed at bringing manufacturing jobs back to the US. Coyle’s focus on a statistical infrastructure to better measure and understand where value lies in global production networks could not be more relevant.

The Measure of Progress: Counting What Really Matters by Diane Coyle Princeton £25, 320 pages

Alan Smith is the FT’s head of visual and data journalism

Join our online book group on Facebook at FT Books Café and follow FT Weekend on Instagram and X

Read the full article here