Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

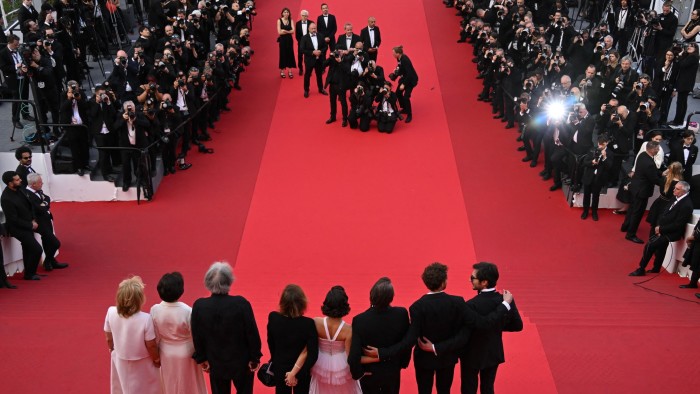

There is only one Cannes Film Festival. Or is there? Depending on whom you speak to, experiences vary. While in the hallowed halls of the Palais des Festivals et des Congrès art house auteurs are showered with enthusiastic ovations, in the basement (or “bunker”) a few floors below and on the surrounding streets, hopeful first-timers tout shoestring productions to anyone who’ll listen.

Jean-Luc Godard experienced both. It is the nervy neophyte of 1959 we see come to Cannes on stolen funds in Richard Linklater’s Nouvelle Vague, an irresistibly effervescent telling of how the great director’s game-changing Breathless was born. This is Godard the disrupter (played by Guillaume Marbeck), shooting guerrilla-style in Paris without lights, permits and often without a script. It takes some serious chutzpah for an American to bring a film about the French New Wave to Cannes but Linklater pulls it off with considerable comic panache and affection.

After this love story to cinema came one of a more conventional kind in The History of Sound. Boasting not one but two of today’s fastest rising stars in Paul Mescal and Josh O’Connor, this delicate, touching film follows two ethnomusicologists collecting folk songs Alan Lomax-style in 1910s New England. The actors’ performances harmonise beautifully together and the direction by Oliver Hermanus (Living) has similar virtues to the music the story extols, with no tricksiness, no unnecessary embellishment and no false notes.

What Julia Ducournau will do next is always anyone’s guess. Having turned heads and stomachs with her 2016 schoolgirl cannibal debut Raw, she conquered Cannes in 2021 with the weirdly warm-hearted tale of mutilation and metamorphosis Titane. Now comes Alpha, which is neither as out there nor as good as Titane — but still pretty out there and pretty good all the same. Its time-hopping tale of an Aids-like epidemic that gradually turns the infected into striking marble statues proved immediately divisive. Incorporating family drama, sexual awakening and addiction ordeal, its constituent parts did not entirely cohere but it contained some of the most striking images of any film here. Ducournau’s status as France’s First Lady of Body Horror seems assured for now, although Coralie Fargeat (The Substance) will no doubt soon re-enter the chat.

Two more films led by women came from France: Hafsia Herzi’s low-key but well-acted lesbian coming-of-age drama The Little Sister and Dominik Moll’s police procedural Dossier 137, which followed a Paris cop’s internal investigation into a gilets jaunes protester’s beating by a riot squad. Italy meanwhile offered Mario Martone’s Fuori, a celebration of feminist writer Goliarda Sapienza that managed to tell us almost nothing about her writing or her politics.

The first 100 minutes or so of Oliver Laxe’s Sirāt were among the best of the fest, with a superb Sergi López scouring outdoor raves in Morocco for his missing daughter with his school-age son in tow and joining a band of punkish revellers. But after a second-act twist that hit like a sledgehammer, this propulsive Spanish offering suddenly stumbled into an explosive denouement that I found arbitrary and deeply unsatisfying. Life is random and cruel, it seems to say, so you might as well enjoy it while it lasts.

Similarly glib messaging (or lack of it) could be found in Ari Aster’s Covid-era Western Eddington, which pits Joaquin Phoenix’s conservative New Mexico sheriff against right-on, mask-on mayor Pedro Pascal. Aster constructs a satirical microcosm of Maga-era American division and paranoia, but then proceeds to do little with it before a final-act shootout that pointlessly puts the gory into allegory. The film also highlighted one of the running themes of this year’s selection: masculinity in crisis. Even more than ideological difference, Phoenix’s sheriff is spurred into vengeful action by his sexless marriage to his wife Louise (Emma Stone), the maddening memory of her past dalliance with Pascal’s mayor and the overtures emanating from a conspiracy-theorist cult leader (Austin Butler).

There was worse to come for male-kind in Lynne Ramsay’s eye-watering portrait of postnatal meltdown Die, My Love, in which Robert Pattinson plays a feckless husband watching his neglected wife (Jennifer Lawrence) unravel violently after they relocate to remote rural Montana and have their first child. While he grows increasingly impotent in every sense, she self-medicates by chugging beer, masturbating compulsively and losing herself in the reverie of childish games as sanity slips away. It’s a firecracker performance from Lawrence, who emits a powerful array of death stares, terrifying calm but also terrific comic timing in a film that combines notes of horror, black comedy and gothic fairytale.

Silky smooth actor Fares Fares gets off to a better start in Eagles of the Republic as a philandering Egyptian matinee idol (“The Pharaoh of the Screen”) who has it all until he enters into a Faustian pact with the authorities by agreeing to play the country’s president, Abdel Fattah al-Sisi. What surprises initially is the brazenly irreverent comic tone of the script, but we go from belly laughs to gut-punches as Swedish director Tarik Saleh changes tack abruptly towards political thriller and the sobering realisation that scheming politicos are sometimes better actors than actors themselves.

Brazil’s Wagner Moura embodied a more dignified vision of manhood in the 1970s-set The Secret Agent. Director Kleber Mendonça Filho dials down the genre excesses of 2019’s Bacurau for the Recife-set thriller about an academic on the run from a vindictive rightwing industrialist in thrall to the country’s junta. More meandering and less hard-hitting than Walter Salles’s recent hit I’m Still Here, it did include the B-movie delights of a severed hairy leg terrorising the local populace and a marvellous turn from Tânia Maria as a benign old busybody who might just be a subversive mastermind.

Mendonça was also one of the 380 signatories of a letter condemning “the genocide taking place in Gaza” and the killing last month in an Israeli air strike of Palestinian photojournalist Fatima Hassouna, one of the main subjects of the documentary Put Your Soul on Your Hand and Walk, showing in one of the festival’s smaller sections.

No films from Palestine or Israel made it into the main competition but Ukraine was represented by the well-established Sergei Loznitsa. His Two Prosecutors couldn’t help but evoke Kafka from almost the first frame as it followed a young idealist trying to get a political prisoner’s case heard in Stalin’s Soviet Union and coming up against the unstoppable machinery of an oppressive state.

Away from the competition for the coveted Palme d’Or, another recurring feature of this Cannes has been actors stepping behind the camera. Three marquee stars found their way into the second-tier Un Certain Regard section with directorial debuts. Scarlett Johansson arrived with Eleanor the Great, a grating comedy of Jewish cultural appropriation starring June Squibb that is as sickly sweet as Manischewitz wine and mines a Holocaust survivor’s story for easy sentiment. Some were enthused about Harris Dickinson’s Urchin; for me it was a derivative drama in the Ken Loach mould with Frank Dillane starring, not always convincingly, as a homeless drug addict trying to get his life back on track. Better was Kristen Stewart’s The Chronology of Water, a highly charged adaptation of Lidia Yuknavitch’s memoir of childhood abuse, sexual abandon and creative self-discovery that was buoyed by a fiercely committed performance by Imogen Poots.

Chronology’s impressionistic exploration of memory and lingering trauma bore similarities with the superior German competition entry Sound of Falling. Constructed of fragments of memory often seen through a child’s eyes, Mascha Schilinski’s film spans three different time periods on the same farm and speaks of generational trauma; it seems haunted by the spirit of Michael Haneke, in particular his White Ribbon.

At press time there were still films to come from, among others, Iranian dissident director Jafar Panahi, American indie luminary Kelly Reichardt and Belgian two-time winners the Dardenne brothers. The question now: which films will jury president Juliette Binoche and her cohort garland with awards? They will have their work cut out to reach consensus in a strong edition of the festival in which both revered regulars and up-and-comers delivered. Not quite a new wave but plenty of encouraging ripples.

Festival ends May 24, festival-cannes.com

Find out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend on Instagram, Bluesky and X, and sign up to receive the FT Weekend newsletter every Saturday morning

Read the full article here