A mirror installation that declares, in large white capital letters, “I love beauty it’s not my fault” looms large over the main gallery at PM23, the Fondazione Valentino Garavani and Giancarlo Giammetti’s new cultural space. It’s housed in a late-1800s building, originally a school and printing house, near Rome’s Spanish Steps.

The phrase was famously uttered by couturier Valentino Garavani in a 2008 documentary. He started the fashion house Valentino in 1960 with friend and business partner Giancarlo Giammetti, and now the pair are focused on the philanthropic, social and cultural mission of the foundation.

A stone’s throw away, in his office on Via Condotti, Giammetti says they opted to open the foundation’s inaugural exhibition in the newly renovated space with the quote from the 93-year-old designer “because beauty is so much more than just aesthetic. I know people sometimes perceive it as superficial, but for us it’s true, it’s one of the few treasures we are left with, the only one capable of countering ugliness and trauma.” The foundation’s new cultural space, named PM23 after its address at Piazza Mignanelli 23, is a testament to the duo’s artistic legacy.

The show is titled Horizons/Red, and the colour is its fil rouge thanks to a selection of 80 pieces from Garavani’s fashion archive and artworks. A vibrant scarlet was his signature, and his most iconic red dresses are showcased, in different lengths, designs and fabrics, including the original 1959 knee-length strapless Fiesta dress, with large red roses applied to the skirt. Artworks on display include pieces by Picasso, Jeff Koons and Andy Warhol, some from Garavani and Giammetti’s personal collection.

Giammetti explains that when their friend Warhol offered to create Garavani’s portrait, now on show at PM23, the couple initially thought it was a casual offer and only belatedly realised they were going to have to pay for the painting. “[By accepting Andy’s offer to draw Valentino] we had implicitly commissioned him, but we didn’t have the money to buy the paintings at the time . . . Several years went by before we did,” Giammetti recalls.

“It was a difficult start, we got kicked out of this place in the early 1960s and we ended up sharing an apartment with a cat lady on Via Gregoriana . . . We would have our aristocratic customers come over for fittings and the place would smell like cat pee,” he remembers. “Luckily, within a year we were able to secure the last floor of the palazzo on Piazza Mignanelli.”

Over the years, Giammetti, now 83, held the financial reins of their fashion empire, having helped his partner recover from the initial financial distress. “Almost as soon as we met I asked him for the books and his accountant’s contact,” says Giammetti, who became Garavani’s business partner soon after meeting the designer.

Now he and Valentino are eager to give back to Rome and its local community through the foundation. They are currently financing multiple projects including initiatives supporting Rome’s children’s hospital Bambino Gesù. They also have new exhibitions planned at the space on Piazza Mignanelli.

“Rome really is the great beauty, in every possible way, it absorbs you. The city means so much for us and for the maison Valentino,” says Giammetti.

Giammetti and Valentino met by chance at a café on Via Veneto in the early 1960s, during the period known as la dolce vita, named after film director Federico Fellini’s masterpiece and referring to a pleasure-filled lifestyle. Giammetti was a regular in the area, where his father owned an electrical appliances shop, and was waiting to go clubbing. The designer had recently moved to the capital from Paris, and, according to Giammetti, “was kind of lonely. So he asked if he could sit with me and we started talking.”

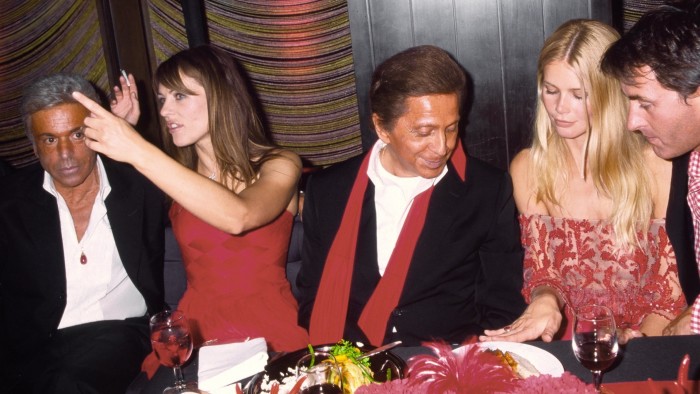

The fortuitous encounter would end up shaping a partnership that lasted half a century, until their retirement in 2007 (the Valentino company was sold in 1998 to the conglomerate HdP) and that has left a permanent imprint on the global fashion industry. Valentino’s refined, elegant aesthetic earned him the nickname, coined by the late Women’s Wear Daily publisher John Fairchild, “the sheik of chic”, was a favourite among personalities of the past including Elizabeth Taylor and Jackie Kennedy and current Hollywood stars such as Nicole Kidman, Anne Hathaway and Gwyneth Paltrow.

Valentino’s last fashion show in Rome 17 years ago and the exhibition of 300 of his designs at the Ara Pacis, a magnificent Roman monument in honour of the goddess of peace, was the designer’s formal farewell to the city and the fashion industry. “We opted to leave when the party was still full,” says Giammetti.

He explains that this new show is “very different”, and the foundation’s activity isn’t really about fashion as much as it is about “beauty and art” and what the duo want to be remembered for.

I ask whether he’s nostalgic about the dolce vita and the industry of the 1980s and ’90s. He muses that “maybe the names like Armani, Valentino, Versace, Prada, Givenchy or Chanel will no longer exist in the future, it’s the concept of the creative director that has changed . . . it’s confusing . . . It’s not clear what is being offered to customers, and egos have become more important than the brand.” In his opinion, “There are few creative directors, like Giambattista Valli, that have had the courage to go on and launch their own successful label, and it makes you wonder.”

Last year, Valentino (which is now owned by Qatar’s Mayhoola investment vehicle, while Kering has a 30 per cent stake) hired former Gucci star Alessandro Michele to replace Pierpaolo Piccioli as the label’s creative director.

Giammetti declines to comment on the choice but observes more broadly that there’s been a general shift in the concept of fashion houses’ creative direction, where “designers are paid millions to be themselves not the label [and its heritage] . . . and this is a big problem because there’s a whole generation of designers all going in the same direction, drawing inspiration from each other, going through revolving doors and it’s confusing.”

Having spent more than 60 years in the luxury industry, Giammetti feels well placed to reflect on its current state.

“Many of these new designs work well for [marketing] purposes, or clickbait on social media, but where do you go from there? Who wears this stuff?” he asks. “Back in the 1970s in Italy you had Valentino but you had lots of other names like [Gianfranco] Ferré, Armani, Krizia, which gave the industry a big push . . . Where are these creatives today?”

Asked whether the main issue is lack of creative vision or lacklustre investments and a scarce institutional ability to safeguard craftsmanship, Giammetti says that “short-termism” is the main issue affecting both the creatives, the investors behind the brands and the institutions. “The fashion industry is going to be turned upside down [by the current changes], though the direction of travel isn’t so clear, so I’m not exactly sure what to expect.

“We are focused on art now, and we’ve decided to mix it with fashion in this first show at PM23, which I think goes to show that both forms of [creative expression] are important parts of the global cultural industry . . . I believe fashion could be a form of art, perhaps some designers were artists . . . but fashion needs to be worn as well.”

‘Horizons/Red’ is at PM23, Rome, until August 31

Follow us on Instagram and sign up for Fashion Matters, your weekly newsletter about the fashion industry

Read the full article here