Tony Iommi clutches his chest in shock and staggers backwards. To adapt the spooky opening words of his band Black Sabbath’s first album from 1970, the foundation stone of heavy metal as a genre: what is this that stands before him?

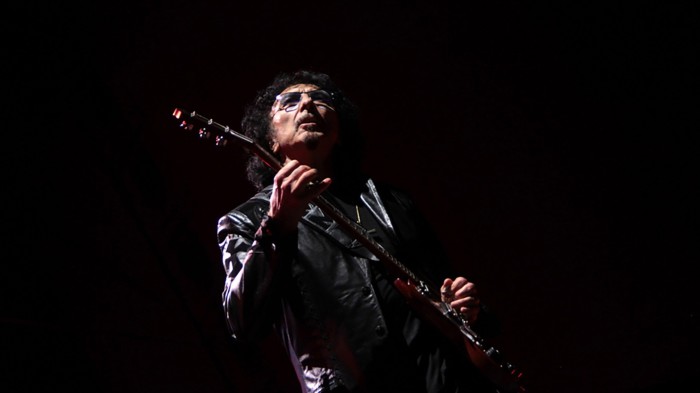

The answer is me, striding up the path to the guitarist’s Cotswolds home through the rain, catching him by surprise as he comes to the front door with an umbrella. The 77-year-old “king of the heavy riff”, as he was dubbed by Metallica’s James Hetfield, is dressed (of course) in black, with dark curly hair and a goatee. Momentarily, he looks as though he has seen one of the evil spirits that throng his venerated group’s songs.

But it is my turn to reel back in shock when I reach him. “Sorry, I can’t do it today,” Iommi says cheerfully in his Birmingham accent, eyes obscured by tinted glasses, “What?” I splutter. “I can’t do it today,” he repeats, smiling.

The awful notion of a wasted two-and-a-half-hour journey from London dawns on me. But my leg is being pulled: Iommi is an inveterate practical joker. “I can’t help it,” he chuckles, leading the way to the inner sanctum of his recording studio.

Next month, the guitarist and his three fellow founding members — singer Ozzy Osbourne, bassist Geezer Butler, drummer Bill Ward — will bring the final curtain down on Black Sabbath. They are staging a farewell concert at Villa Park, the biggest football stadium in Birmingham, the Midlands city where Sabbath formed in 1968. Heavy metal and hard rock royalty will converge to pay tribute, with appearances by Metallica, Slayer, Lamb of God, Gojira and many others.

“I’m so honoured that all these bands have come forward to support us,” Iommi says. “The biggest bands in the world, it’s just unbelievable. And we’ve got to stand up to that.”

Curated by Rage Against the Machine guitarist Tom Morello, the one-off spectacular is called Back to the Beginning. The title nods to Sabbath’s Birmingham origins, but also their reputation as the creators of heavy metal. Each member was crucial: Ward for his jazz-honed drumming, Butler for his bass groove, Osbourne for his potent shriek and wild-man stage antics. But Iommi was the architect. Riffs for classics such as “War Pigs” and “Paranoid” are masterpieces of weight, balance and tension.

The show will be the first time that the original foursome have played together since 2005. How does Iommi feel about their valedictory performance? “A bit nervous really,” he says. “It was second nature before. But this time it’s going to be a lot of pressure because it’s the unknown. We don’t know how many songs we’re going to do and we don’t know how we’re going to be.”

Our meeting takes place a few weeks before the rehearsals. Among the unknowns is Osbourne’s condition. The singer’s health is precarious. Parkinson’s disease and injuries, such as one to his spine in 2003, have left him with restricted mobility. He spoke in February of being unable to walk. With customary élan, he has just released a limited edition stock of empty iced tea cans containing traces of his DNA, each one selling for $450. His message to fans: “Clone me, you bastards.”

“As far as I know, he’ll be in a throne,” Iommi says of Osbourne’s plans for Villa Park — a static presence. “Unless,” he muses, “he’s got an electric throne.” The guitarist was himself diagnosed with lymphoma in 2011, which requires managing, but he looks well. “Most of me and Ozzy’s discussions these days are about who’s got what,” he says.

Surely there will be a practical joke or two, for old times’ sake. “Quite possibly,” Iommi says. “We’ve never ever gone without playing jokes on each other so I imagine something will come out.”

Hopefully no one will be hospitalised this time. “They went a bit far, some of them,” he concedes. On one infamous occasion in Los Angeles, a very drunk Ward was stripped naked, spray-painted gold and covered in lacquer.

“It was really mad. Bill was laughing and then suddenly” — Iommi imitates the distressed sound of the drummer having a seizure. “Oh no! I had to phone the ambulance. They said, ‘What’s wrong with him?’ Well, he’s painted gold. ‘What?!’ And they came out and really chewed me and Ozzy out. You look back and go: oh my God, did that happen? I mean, we could have killed him really.”

Iommi, who lives with his fourth wife, Swedish rock musician Maria Sjöholm, relates this hair-raising tale with good-humoured relish. Behind him stretches a recording console with numerous sliders and knobs. Sound baffles line the walls, alongside a large wooden cross. A plush toy rat is on top of a speaker. There are many electric guitars in racks. He was playing one before I arrived; hence the white tape on the tips of two fingers of his right hand — the most consequential injured digits in rock.

The churning, sludgy sound that Black Sabbath pioneered — the primordial soup from which heavy metal emerged — partly owes its origins to an industrial accident. Raised in Aston, a tough working-class district in Birmingham, by a father who was the son of Italian immigrants and a mother born in Palermo, Iommi was 17 when the accident occurred in 1965. On the final day of a disliked job in a sheet-metal factory, he lost the ends of his middle and ring finger when filling in for a co-worker on an unfamiliar metal-cutting machine.

At the time, he was guitarist in a pre-Sabbath band that was about to tour Europe. “I went to the hospital and they said, ‘You won’t be playing again.’ I couldn’t accept that. I thought, there’s got to be a way,” he remembers. His solution was to create thimbles from the tops of washing-up liquid bottles. These evolved into finger guards moulded from plastic and scraps of fabric from an old leather jacket. Later on, a hospital used to supply him with prosthetic arms whose fingertips he customised.

“The thimbles, I’ve still got them,” he says, going to the recording console and returning with a battered tobacco-style tin. He shows me the contents. “They’re very primitive.” He used one recently while making a video for Robbie Williams’s latest single “Rocket”, on which he plays spirited lead guitar — “and my bloody thimble flies off because I hadn’t glued it! Robbie’s going . . . ” He mimes the singer searching frantically on the floor for the rogue protector.

As a left-hander, it is his fretting fingers that are affected, the ones placed on the neck of the guitar. He persuaded a Welsh company to make lighter strings for him (non-existent in the early 1970s) and invested in a Birmingham company run by the innovative luthier John Birch to obtain suitable instruments.

As a result, Iommi developed a lower, thicker tone than other lead guitarists, with solos that change every time he performs them. Critics at the time overlooked the inventiveness: they treated the working-class Midlanders of Sabbath as proletarian hooligans making a racket. “It was because it was so different,” he says. “People wouldn’t accept it. We plodded on through all the bad comments.”

B-movie occultism and industrial quantities of drugs, as celebrated in the 1972 cocaine anthem “Snowblind”, added to their brutal reputation. So did crazy pranks like the spray-painting incident. But Iommi’s guitar playing can be delicate, too, as with his tender folk-rock turn in 1971’s “Solitude”. Among his influences are jazz guitarist Django Reinhardt, who played with a mutilated hand and inspired Iommi to continue after the accident.

Black Sabbath are technically coming out of retirement for their Villa Park show. Their 2016-17 tour was unambiguously called “The End”. Iommi, the only constant fixture in the band amid multiple line-up changes — including different frontmen — was initially dubious about returning. But the presence of Ward, who was not present for The End, helped to sway him. So did the decision to give the proceeds to various charities, including one dedicated to Parkinson’s disease.

“It’s like brotherhood, you know. We’ve had ups and downs but we’re all still in contact with each other,” he says. The song he most looks forward to playing? “The last one!” he laughs — but he then reels off some of the classics: “Iron Man”, “Black Sabbath”, “War Pigs”, “Paranoid”.

“They’re the symbols of the band really,” he says. Their indelible riffs will ring out one last time, eagerly received by tens of thousands of fans and the younger musicians that have followed in Black Sabbath’s wake. Message to them all: clone that, you bastards.

‘Back to the Beginning’ will be livestreamed on July 5. Tickets at backtothebeginning.com

Find out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend on Instagram, Bluesky and X, and sign up to receive the FT Weekend newsletter every Saturday morning

Read the full article here