Few people would pinpoint a former town hall in inner-city Manchester as the crucible of one of the most significant political movements of the 20th century. But in October 1945, the city’s Chorlton-on-Medlock Town Hall hosted the fifth Pan-African Congress, a gathering that eventually spurred African and Caribbean nations into wrenching their independence from western imperial powers.

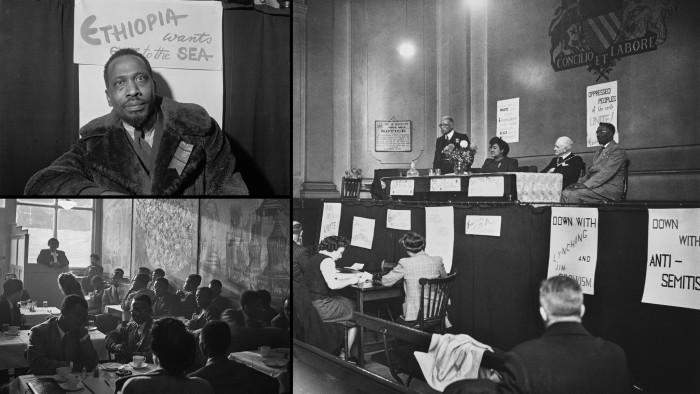

Delegates from around the world included four future African presidents and premiers, as well as African-American activists at the forefront of ending Jim Crow laws, among them WEB Du Bois. The congress made uncompromising demands for the end of colonialism and its racist ideologies, and launched a rallying cry for the right to self-governance.

Kwame Nkrumah, who would lead the British colony of Gold Coast to independence in 1957, summed up the vision of Black self-determination the congress put forward: “We went from Manchester knowing definitely where we were going.”

Eighty years later, playwright Ntombizodwa Nyoni and director Monique Touko’s Liberation reimagines that heady week, and asks if the pan-African revolution ever arrived at its true destination. The play, which debuted at the Royal Exchange Theatre at Manchester International Festival this month, centres on George Padmore, the Trinidadian activist and a key organiser, who is torn about passing the torch to a new generation with far more radical demands.

The play was conceived and written over several years, but Nyoni says crafting the script was a fluid exercise, shaped by the pandemic and events such as the murder of George Floyd. “It always felt like this live thing that was responding to the world and where we were at,” she says.

“That causation around hope and hopelessness just kept playing on my mind all the time. If you are an activist, if you want to engage in this movement, how do you continue to do that work if you’re still continually seeing oppression or brutality?”

The first Pan-African Conference, as it was then called, was held in 1900 in London and mainly sought moderate reforms to colonial rule. By 1945, in the new world order emerging from a devastating world war, pan-Africanism had evolved from its origins as a fringe campaign propagated by a handful of educated African agitators in smoky cafés to a popular political movement that could no longer be ignored.

At its core, the new manifesto called for a self-governing Africa with no borders and demanded equal rights for all people of African descent. Even the word “Africans”, which at the time was used derogatorily by racists, was reclaimed as a source of pride.

“It signalled a new kind of spirit and approach, which was a demand that colonialism should be brought to an end,” notes the historian Hakim Adi. “This was the first congress . . . that threatened the use of force, if necessary, to bring about that demand. But the most important aspect . . . is that it set out a vision of a future Africa — an Africa without colonial boundaries, and without the political institutions of colonialism.”

For all the big, existential questions it poses, the drama of Liberation also lives in the exploration of private moral dilemmas and quieter moments of friendship. There’s a danger, Touko notes, of history becoming purely “about facts and theories”. Instead, Nyoni’s writing “centred the human — they’re messy and they’re vulnerable and they’re complicated and there’s a real intersection of class, of gender, of race”, Touko adds.

The writing makes no bones about what happens behind the scenes of a revolution. Alma LaBadie, a Jamaican social worker, and Amy Garvey, who was married to Marcus Garvey until his death in 1940, become fast friends as they struggle between the double bind of elevating Black men in the face of white supremacy, even as Black women themselves are often sidelined.

“Beyond them being activists and political figures . . . underneath, it’s different people with different reasons as to why they’re there,” says Nyoni. It’s hard not to think of parallels with contemporary movements on the left, whether it’s the fracturing of the Black Lives Matter movement or of environmental activist group Extinction Rebellion.

The location is also pivotal, with Manchester functioning almost as a character itself. “This conference would have been very different in another location,” says Touko. “There was something specific about Manchester, the trade union history of Manchester, the working people of Manchester. People are really welcoming here. So the idea of housing Africans from all over the continent, from the Caribbean — there was a sense of community that was built here, and that was testament to Manchester specifically.”

The play adds to a growing crop of histories that have widened the conversation around the Black experience in Britain beyond London. Author and journalist Lanre Bakare’s book We Were There, published this year, stands as a beautiful corrective to the view that Black resistance begins and ends in the capital. “For a lot of people, black British history begins in 1948 with the Windrush docking in Tilbury. Well, actually three years before, you’ve got this crucial meeting,” says Bakare.

“It happened in Manchester because there’s this Black infrastructure,” he adds: Black-owned hotels, tea rooms, bookshops and clubs that became melting pots for discussions and debates. At the Cosmopolitan nightclub, he notes, Jomo Kenyatta, the future leader of Kenya, worked for a time as a maître d’hôtel.

The reverberations of Britain’s imperial past are still felt — not least in the creative team’s own lives. Touko’s parents are from Cameroon, which is today battling an insurgency borne out of colonialism, as English-speaking Cameroonians fight a bloody battle for independence against the francophone majority.

The ideas of the congress “don’t stop at the point at which I stop writing or the play ends”, Nyoni says. “You still find [Black people] having to have the same conversations about freedom, about the right to speak, the right to be human in the world.”

To July 19, factoryinternational.org

Find out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend on Instagram, Bluesky and X, and sign up to receive the FT Weekend newsletter every Saturday morning

Read the full article here