For a moment, the audience didn’t seem to understand what was going on. It was nearing midnight on the opening evening of the Arles photography festival; photographer Nan Goldin had just received the Women in Motion Award from the luxury group Kering. Then the French writer Édouard Louis sprang up and joined her on stage, cueing a slideshow depicting the conflict in Gaza — body bags, rubble, children in distress, all shown in tense silence on a huge screen. Afterwards, they launched into a joint excoriation of Israel’s actions, which they described as “the first live-streamed genocide”. “How is it that we’re so detached?” Goldin asked. “We watch children dying on Instagram,” added Louis. “We think saying ‘This is horrible’ is enough.”

The surprise was not so much the stance on Gaza — Goldin has been vocal on the topic before — or Goldin’s insistence on speaking out, given her crusade against the Sackler family and the opioid industry. It was more that a photographer should query whether photographs actually do that much. What do pictures achieve? Are they enough?

At this year’s Rencontres d’Arles — the world’s oldest event of its kind, where image-makers from across the globe swarm the French city — those questions were everywhere. Previous editions have probed what photography is or isn’t, or attempted to broaden its scope. Now, in the era of AI-generated imagery, post-truth conspiracy theories and media blackouts in conflict zones, something more existential seemed at stake.

One response came in a show, Losing North, by Luxembourger photographer Carine Krecké, staged in the Chapelle de la Charité near the centre of town. Inside this baroque vault Krecké has installed screens narrating her journey into the dark heart of the Syrian civil war. In 2018, seven years into the conflict, she stumbled across photographs on Google Maps documenting the destruction of a Damascus suburb by then president Bashar al-Assad’s forces. Whoever had posted them had risked their life; fascinated, Krecké tried to find out more, and fell into a baffling warren of social media posts and satellite imagery.

On one satellite photograph, on top of a khaki smudge of what could have been rubble, she found a geotag reading “surgical hospital, please?” — possibly evidence of a pulverised medical facility, perhaps also a plaintive cry for help. Over blurred images on the screen alongside, Krecké’s voice narrates a quest through censored, inconclusive Facebook videos. In this exhibition, legible images are few and far between; that is the point. “Why do certain conflicts disappear into black holes?” she asks.

A conflict that could hardly be described as invisible is the one between the mafia and the Italian authorities, which has been going on for decades. That we can picture its combatants so precisely — the bodies sprawled on pavements, the keening widows — is largely owing to the courage of photojournalists such as Letizia Battaglia, who risked their own lives documenting Sicily in the 1980s and early ’90s, when thousands were gunned down in Palermo’s streets or blown up in their driveways.

Battaglia, who died in 2022 and is being celebrated with a retrospective here, had a remarkable life, teaching herself photography while bringing up three daughters in her thirties, then launching herself professionally soon afterwards. She began photographing the mafia in 1974, becoming the photo editor of L’Ora newspaper.

These black-and-white images are severe and shocking, not just because of their horror, but because of Battaglia’s instinct for the surreal — a gift shared with the godfather of crime-scene photography, Weegee, whose work she surely learned from. Battaglia’s talent was for getting unflinchingly intimate with her subjects: “at the distance of a punch or a caress”, as she once put it.

One victim lies face down in the dirt next to a slick of his own blood, T-shirt rucked up to reveal a tattoo of Jesus’s face on his shoulder — Battaglia called the picture “I due Cristi (The Two Christs)” (1982). Another image, a close-up portrait of an elegant young woman, eyes closed, lips parted, face half-shrouded in shadow, could almost be on the pages of Vogue. But she’s not a model: she’s the widow of a bodyguard killed in the line of duty.

The exhibition is called Always in Search of Life, and Battaglia had an instinct for that too, evident in her images of children, who often look like grown-ups in this adult world run amok. Yet she doubted the value of her work, and eventually eschewed photojournalism for politics and publishing in the 1990s. “Photography changes nothing,” she once declared.

Elsewhere, though, I wasn’t so sure. One transformation is wrought in the cloisters of Saint-Trophime by artist Raphaëlle Peria and curator Fanny Robin, who combine to remake Peria’s hazy memories of a childhood journey down the Canal du Midi for the BMW Art Makers prize. Family snaps of the voyage have been printed large; then the artist has made incisions in them with engraving tools so that the white surface of the paper shows through; an obsessively detailed process that perhaps tries to get at the difficulty of excavating our past.

And in recent editions the festival’s curators have striven to open the door to new images and voices. A multiyear project to put together a group show from Australia, On Country, the first of its kind here, has finally and gloriously come to fruition. Featuring 17 artists and collectives, it draws a distinction between “land” — a colonising term, argue its organisers, redolent of economic or political capital — and “country”, a term deeply felt by people of Indigenous heritage, which embodies a living connection to a place that has been continuously occupied for some 65,000 years.

Europeans brought the camera to Australia in the 1840s, not long after its invention, and were soon using it as an instrument of control and classification. That inheritance is confronted and subverted by Brenda L Croft, who, in honour of early images of Aboriginal people, has made an array of 19th-century-style, 4×5-inch “tintype” portraits of women and girls, Naabámi (thou shall/will see): Barangaroo (army of me) (2019-24). Arrayed around the light-bathed apse of the Église St-Anne, these female faces gaze out at us, calm and composed, accompanied by a luminous recording of a First Nations choir.

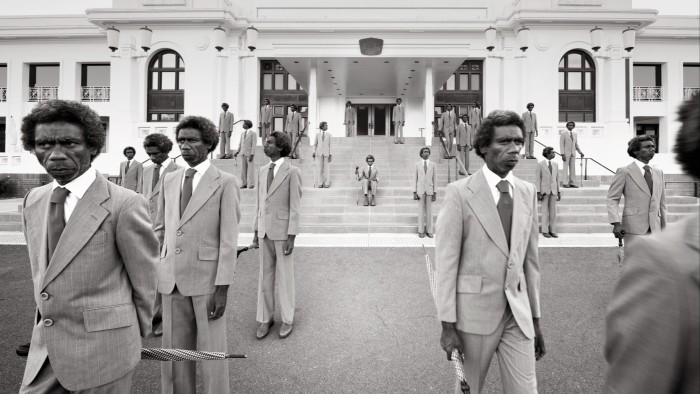

Subversion is also offered by Michael Cook, whose Majority Rule series (2014) wryly imagines an Australia in which Indigenous people run their own country. Using digital manipulation, Cook populates scenes of national monuments and locations with hundreds of versions of exactly the same figure — an Aboriginal man, often decked out in a suit and hat, sometimes braces too. These men of business parade on the pavement, preparing for a high-powered day at the office; in parliament they jab their fingers or flutter their order papers. Given that Australians voted to reject a law enshrining Aboriginal people in the constitution in 2023, the joke now seems bleak.

A tougher inheritance is visible in a photo essay by Tace Stevens, We Were Just Little Boys (2023-24), which tracks a group of Indigenous men who were removed from their communities by the Australian government and resettled in a boys’ home in New South Wales. Stevens contrasts lustrously lit shots of the prison-like site, now a memorial, with images of the men, now in their seventies and eighties. Sometimes their portraits are superimposed on archive photographs of their past selves: old faces whose childhoods were stolen, young eyes that have seen far too much. The impact of scandals like this is, surely, one thing photography — perhaps uniquely among art forms — can bring home.

Nan Goldin did offer her own response to the question of what photography can do. As well as receiving the Kering award, she brought a fresh work, Stendhal Syndrome (2024), installed in another of Arles’ deconsecrated chapels for its first European showing. Born out of Goldin’s Grand Tour-style journeys around major museums, it is half-slideshow, half-film, half an hour long, intercutting pictures of works by the likes of Caravaggio, Canova, Titian and Delacroix with her own frames of friends, intimates and lovers. Over these, Goldin throatily narrates tales from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, weaving them into visual narratives both sacred and profane.

The connection could seem forced, and occasionally it is, but it mostly feels vivid and alive: you notice how Goldin’s portraits instinctively echo classical forms; how Ovid’s world of mutability and transformation, raw desire and blunt violence, is intimately hers. Entwined bodies, tousled sheets, youthful skin shimmering in water, drowsy, blurred light: the images stay with you long after you’ve emerged into the Provencal sun. The syndrome that Stendhal named describes what it feels like to be overwhelmed by great art. As I stood up, I realised the woman sitting next to me was heaving with sobs. Pictures can sometimes be enough.

To September 28, rencontres-arles.com

Read the full article here