Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Food is pleasure, as any chef or diner knows. Whether it’s tasting top-quality produce at peak freshness, rendering daily deliveries into myriad forms, or the less spoken realities of life as a working chef — successfully excavating a £23 tray of cheese to satisfy an unending need to taste. While fine dining is a sophisticated experience, what we chefs actually eat on the job is surprisingly unglamorous. It’s sustenance, so largely utilitarian or oddly domestic: the aforementioned salvaged cheeseboard and stashed away end-cuts of steaks to share after service (an instinctual way to buy favour in any kitchen). Yet it remains enjoyable.

Cooking not just for guests but also for co-workers is one of those joys. At the two-Michelin-starred restaurant where I work, chefs take turns preparing staff meals. More experienced chefs demonstrate their prowess by prepping days in advance; but all chefs aim to be resourceful in how they make use of kitchen scraps, as both a cost-cutting measure and a way to reduce waste. One chef used buttermilk (a byproduct of churning our butter in house) to make pancakes for breakfast and butter chicken for dinner. Last week, I spun an overcooked side of rice into an orange-cardamom-cinnamon rice pudding.

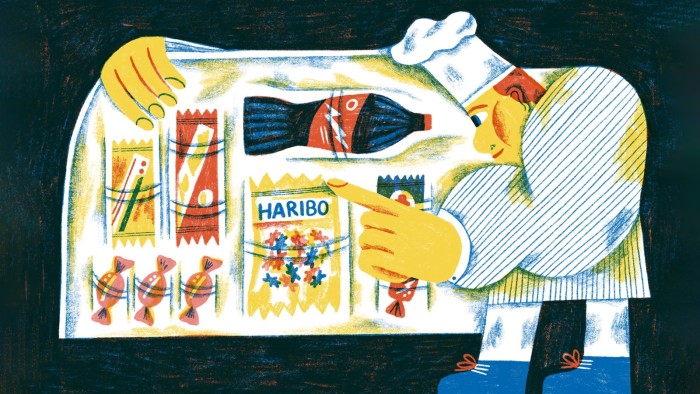

It’s more challenging to romanticise the commercially produced grub that we snack on. An unlikely favourite — one so popular our chef-owner suggested it as currency among London kitchens — is sweet-sour Haribo Tangfastics. Chefs value the sweets for a surprisingly practical reason: storability. They’re tidy little hits of sugar that can be kept in a ramekin stashed in the fridge or just as well sitting in their packet on a warm counter.

One treat that never gets the chance to melt in our kitchen is the M&S Big Daddy chocolate bar. It’s essentially an oversized Snickers that supposedly serves 10. When pressed on what makes this candy so good (at £7.50 a bar, it’s considerably pricier than a bag of Haribos), my fellow chefs either took offence at my doubt or laughed me out of the room.

I received the same incredulous looks when I once questioned why we drink so much lime Coke. Whenever I take orders for drinks at the corner store, an overwhelming majority request it (some have the gall to ask for two). Unlike Tangfastics, this lime Coke allegiance is a cultural effect unique to our kitchen — much like how couples share similar music tastes or friends wear the same sneakers. After all, lemon Coke is probably just as good.

Being a chef in a fine-dining establishment is a physically demanding exercise in pushing culinary boundaries, one that commands a devotion to excellence. But the seriousness of the craft is often misconstrued as a reflection of the chef. We’re just ordinary people eating mostly ordinary food. The only real difference? We get to do it in a really nice restaurant five days a week.

Cheryl Cheung is a commis chef at Trivet

Find out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend Magazine on X and FT Weekend on Instagram

Read the full article here