Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

A few weeks ago, I sat next to a former England footballer at lunch. She had suffered a serious ankle injury in her early thirties. After researching how to recover, she decided to turn vegan. Medical staff were sceptical until her statistics proved better than ever. Today, her only regret is not changing diet sooner.

Such stories have become rarer. Veganism was once the biggest food trend. Now the zeitgeist is elsewhere. Google searches for the word “vegan” rose steadily after 2010, peaked in early 2020 and have dropped since. Sales of Beyond Meat and Impossible Foods, which make arguably the best vegan burgers, are falling too.

Eleven Madison Park, the high-end New York restaurant which went plant-based after Covid-19, is reintroducing meat to its menu. One high-profile vegan, crypto entrepreneur Sam Bankman-Fried, is in jail. Another, New York mayor Eric Adams, turned out to like eating at fish restaurants.

Of course, vegan options are more common than in the past. But given the low base — fewer than one in 10 people in western countries say they are vegetarian or vegan — meat-free advocates were relying on mass conversion. That isn’t happening.

What went wrong? One answer is that the vegans could never win. They were trying to upturn thousands of years of human cuisine. Pea-based sausages were not electric cars: they weren’t almost as satisfying as the products they sought to replace. In blind taste tests, many vegan alternatives performed poorly (although, in real life, at least part of diners’ disappointment was surely in the mind). According to this argument, socially conscious consumers were willing to try vegan alternatives, but they weren’t prepared to stick with them.

But quite a lot of people might have eaten vegan — if another trend hadn’t come along. That trend was avoiding ultra-processed foods. Suddenly, healthy eating came not from less meat, but from fewer additives. The meat industry exploited the idea that vegan foods were artificial.

In fact, studies suggest that some plant-based alternatives do not have the same health risks as other processed foods. The doctor and author Chris van Tulleken, a staunch critic of ultra-processed foods, said a vegan diet “can be very healthy”. Such nuances were lost.

Food trends are fickle. Lately, influencers and gym bros have talked up the benefits of eating more protein. It’s no matter that most westerners eat more than enough protein, and that a vegan diet can give you all the amino acids you need. When people think protein, they think meat, eggs and whey powder, a byproduct from cheesemaking. The idea of cutting down on meat has been squeezed from the conversation.

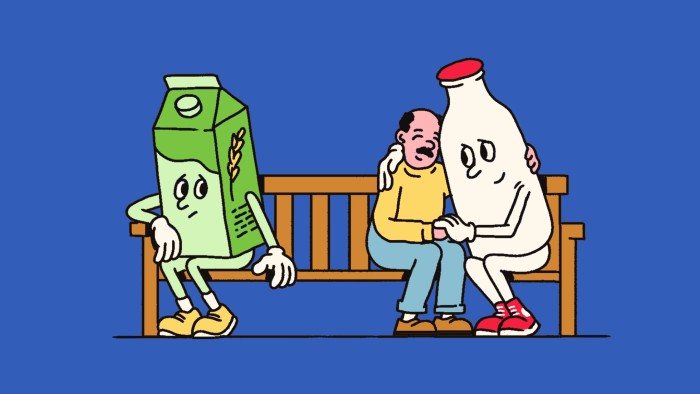

Meanwhile, governments never intervened to help plant-based diets in the way that they helped electric cars. They even made vegan foods less attractive. In Europe, oat milk must legally be sold as “oat drink”.

Even with all of the above, the retreat of veganism wouldn’t have been possible without another ingredient: the decline in idealism. Not long ago, liberals in particular were prepared to make sacrifices in the hope of a better society. Faced with overwhelming bleakness — Covid, Ukraine, high energy costs, Donald Trump’s re-election, Gaza — they have lost faith. They understandably wonder if small changes matter; they want to escape to the things that bring instant joy — meat, cheese, long-haul holidays.

Veganism wasn’t meant to be like other food fads: it was intended to benefit not just the individual but society as a whole. Eating less meat would reduce greenhouse gas emissions and animal suffering. The evidence is clear. But right now we can’t be bothered.

Vegans are used to being mocked as humourless (Ricky Gervais and Jon Stewart are vegan . . .), unathletic (. . . as is Novak Djokovic, more or less) and uncool (. . . and Woody Harrelson and Ariana Grande). They keep going. Beyond Meat is trying to boost its healthy credentials. It is rebranding as Beyond, and advertising a new protein product with only four ingredients.

But concerns about climate and animal welfare are the bedrock of veganism — the reasons that will keep people feeling good about eating less meat, and that can get governments involved. In Germany, where support for climate action remains strong, sales of plant-based food have kept growing. Elsewhere, vegans will regain the momentum if the public regains a sense of possibility.

Henry Mance is the FT’s chief features writer. Simon Kuper is away

Find out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend Magazine on X and FT Weekend on Instagram

Read the full article here