Josh Safdie is in a room at Claridge’s but Marty Mauser stayed at the Ritz. Luxury London hotels aside, the pair still have a lot in common. Safdie is visiting the UK from New York, an acclaimed director whose latest film Marty Supreme is an Oscars contender. Mauser is its fictional hero, a semi-feral table tennis pro from 1952 Manhattan. Played by Timothée Chalamet, Mauser is gifted and driven, a fast and fluent talker. So is his creator.

“I wanted to use Marty to explore the urgency of dreaming big,” Safdie says. “The movie is like a heist film, but he’s heisting his own fate.”

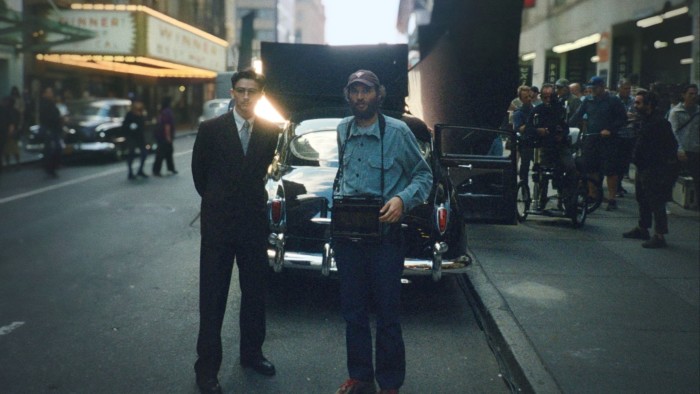

Safdie is 41, with the air of a raconteur. His brand of screwball vérité has built a loyal young fan base. Marty Supreme is another step forward: bigger, wilder. Yet the director says he only half-notices the praise it has won. “I don’t want to sound self-involved, and people connecting with it is surreal and wonderful. But it was an epic undertaking, and even now, it feels private to me.” The film is frequently hilarious. Still, Safdie says he cries watching it.

Today, though, he is relaxed, more than when we last met. That was 2019. Safdie had just released Uncut Gems, co-directed with younger brother and creative partner Benny. The film involved another frantic New Yorker, a diamond dealer played by Adam Sandler. It had been a breakthrough, budgeted at what the brothers saw as a serious $19mn. A cultural splash was made. Safdie, though, had paid a price — friendly in person, but wrung-out.

“Gems had been a 10-year journey,” he says. “For so long, it was a dream nobody believed in, and every moment of that was a humiliation.” But with the movie finally made, Safdie found himself bereft. “I felt hollow. I’d lost my purpose.”

Salvation came with ping pong. Safdie’s partner Sara Rossein gave him an old book, The Money Player, the memoir of one-time US champion Marty Reisman. It became an inspiration. Some of that had to do with the sport, which on screen has a hypnotic energy. “The miniature quality gives it such intensity. It’s the physical proximity. It’s really two people having a conversation.”

But the book was also a portal. Reisman had been part of what Safdie learnt was once a thriving underground table tennis scene in mid-century New York, filled with maestros at a sport with no place in the US athletic establishment. “Wiry Jewish dudes, misfits and outcasts,” Safdie says. They too “had chased a dream nobody respected”. The larger-than-life Reisman would become just one among several models for Mauser.

Another is the star who plays him. Safdie first met Chalamet in 2017. The young actor had just kick-started his own career with coming-of-age romance Call Me By Your Name. Safdie remembers him as a nervy wallflower. But he had vast presence — and more.

“He was this restless dreamer, with an incredible bottled energy, and a vision for himself. That fascinated me as he became a star. I thought, ‘Wow — this kid is doing it!’ And I was shocked filmmakers didn’t explore that side to him. To me, he was always Timmy Supreme.”

And yet Chalamet is only the second-most notable casting coup in Marty Supreme. On screen, the twenty-something rogue aims to seduce an older, married film star, about to make a comeback. Off-camera, Safdie wrote the part for someone who seemed every bit as out of reach: Gwyneth Paltrow, actor and founder of wellness corporation Goop.

“I needed that meta quality, with Gwyneth not having acted in so long. And I wanted her Grace Kelly vibe — that opulence and elegance.”

Serial approaches were made. “She never said no. Her agents wouldn’t even bring it to her. I was constantly saying, ‘Please — just get me in a room with her.’” In the end, her filmmaker brother Jake helped swing a meeting. As Safdie pitched, Paltrow’s assistant offered her the chance to make a polite exit to another appointment. Safdie says it may or may not have actually existed. Either way, she had it “pushed” four times. The director kept talking. “Then she said, ‘I hope I remember how to do this.’”

Paltrow joined a madly eclectic cast. Co-stars include Tyler Okonma, also known as rapper Tyler, the Creator; veteran cult director Abel Ferrara; Fran Drescher, leader of the Screen Actors Guild during the recent Hollywood strikes; and wilfully abrasive TV business personality Kevin O’Leary. All make absolute sense in the film, their real-life personas part of the mix. “We live in a postmodern time, and when you cast, people bring their history.”

But not everyone signed up. Safdie’s regular co-writer Ronald Bronstein returned. Benny Safdie did not. Since Uncut Gems, he had established himself as an actor, appearing in Oppenheimer and more. “He told me he didn’t want to express himself through Marty. And I wasn’t interested in exploring myself through The Smashing Machine [Benny Safdie’s solo directorial debut].” Safdie says he loves his brother’s movie. He doesn’t know if they will work together again.

Marty Supreme obsessed him too much to dwell on the break-up, he says. As well as being his first film directed alone in years, it was also his first period piece. A rabbit hole of scale and detail opened up. “I did go nuts.” If Uncut Gems felt big league at $19mn, the new film is reported to have cost $60-$70mn. Safdie says he was unfazed. “You can’t let that into your head. You never have enough money anyway.”

Working with legendary production designer Jack Fisk, elaborate sets were built of the fleapit hotels and tenements of New York’s postwar Lower East Side. Hundreds of extras were carefully cast. “People said, ‘Listen, these guys are in the deep background.’ I said, ‘I don’t care! If there’s an anachronistic face, we’re screwed.’”

But keeping the past real involved more than sets. As befits a story from 1952, the film also touches on the Holocaust and postwar Japan. Amid the trademark Safdie mayhem, the weight is deftly handled. The director says he wasn’t the highest-flying student. (An English teacher once asked him if it was his second language.) “But I can understand history through the lens of these lives.”

While his grades disappointed, Safdie found another academy: the New York film world, springboard for his scuzzy, funny, hectic movies. And the characters whose tales they tell have all had their hustle. Before Marty Mauser, there was the frenzied Howard Ratner in Uncut Gems, and bank robber Connie Nikas, played by Robert Pattinson in 2017’s Good Time. Some are more wholesome than others. All have pathological self-belief.

“Most kids have a dream. Then they back away. I’m fascinated by the people who don’t, and the ugly beauty of their ambition.”

Safdie himself doesn’t lack for a sense of mission. And yet six years ago, as Uncut Gems became a hit, he says he wondered whether he wanted to make films at all. “I thought about becoming an architect. I’d love to build something public, a library or museum. But I told Ronnie [Bronstein], and he was like, ‘Wait — I got a mortgage now!’”

This time, whatever Safdie does next is more likely to be a movie than a museum. Once more, he has found himself exhausted after another all-consuming project. “You think: what was that all for?” Now, though, he has a clearer answer. “It allows you to dream even bigger.”

‘Marty Supreme’ is in UK cinemas from December 26, and US cinemas from December 25

Find out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend on Instagram, Bluesky and X, and sign up to receive the FT Weekend newsletter every Saturday morning

Read the full article here