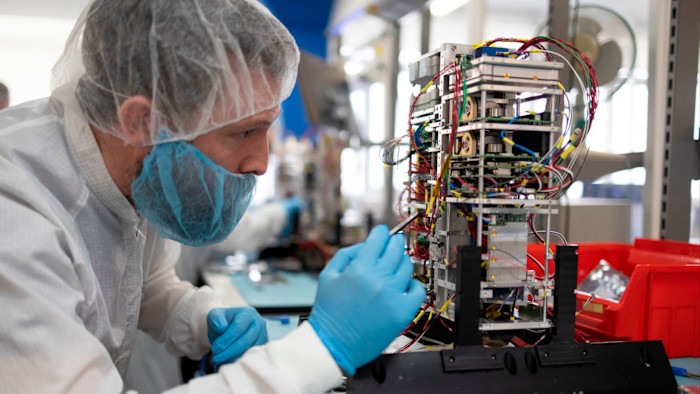

In an anonymous office block towering above the trendy bars of Finnieston, engineers delicately stack guidance devices and solar panels around the “CubeSats” that have turned Glasgow into Europe’s manufacturing capital for these small, modular satellites.

Since its first satellite launched in 2014, AAC Clyde Space has become a leader in the Scottish city’s cluster of manufacturers building them for customers around the world.

The Swedish-backed group also launches its own satellites, offering services for companies such as tracking maritime vessels or observing changes in forests and farmland.

The company is seeing more growth in providing data and services than purely manufacturing the satellites, according to chief executive Luis Gomes.

“The demand is for people to know things,” he said, adding: “Operating satellites is difficult, so many companies don’t want to do that, they want the data.”

As the company transitions from hardware manufacturer to data provider, from next year it will monitor tree cover for signs of disease, replacing the helicopters and drones used by Scotland’s state forestry manager — a product that can then be sold on to large timber companies across the US and Europe.

Its latest venture, Inflecion, aims to enhance operations and security in the maritime industry — even tracking ships that have turned off their transponders by detecting emissions or phone signals. Using technology that is largely the preserve of the military, it will become operational in 2028, with the launch of a constellation of 12 satellites.

Scotland’s space sector, which has benefited from the country’s strong universities, is on the verge of emerging as an integrated industry — spanning from the manufacturing of satellites through to launching them and then analysing the data — placing the nation at the cutting edge of a sector that is central to both defence and commerce.

Glasgow, which builds more satellites than any other city in Europe, is complemented by analytics companies in Edinburgh processing data retrieved from the more than 10,000 active satellites orbiting the Earth.

They are joined by two rocket companies, Orbex and Skyrora, and SaxaVord Spaceport on the Shetland island of Unst, which has emerged as a leading contender to become Europe’s main domestic spaceport.

Now, executives are calling for more government support to keep the UK space industry competitive in the face of a huge increase in European spending.

As Europe reviews its military strategies in the wake of the Ukraine war, Germany has allocated €35bn for space capabilities oriented towards security and defence, such as military satellites and orbital awareness systems.

At last month’s ministerial meeting setting the European Space Agency’s record €22bn 2026-28 budget, Germany increased its pledge by 45 per cent, Spain by 90 per cent and associate member Canada boosted its funding fivefold.

The UK’s allocation, meanwhile, was cut by about 10 per cent.

The ESA, which coordinates intergovernmental space missions, is funded by its 23 members and other associate states. It then aims to provide contracts to member states’ companies and universities in line with national allocations to the body.

“Now it’s very, very difficult to compete with this huge capital given to our competitors on the continent, so it is imperative that the UK actually invests more,” said Gomes. Companies such as AAC Clyde Space received frequent requests to open overseas factories to exploit foreign funding streams, he added.

Richard Lochhead, Scotland’s business minister, said: “Lots of governments are throwing significant investments at the space economy, for commercial reasons, defence and security, it’s really important that the UK government does all it can to not fall behind.”

The UK was investing a “record amount” in space, with £2.8bn allocated to the UK Space Agency through the spending review, a government spokesperson said. “We have deliberately invested in areas which deliver maximum value for UK’s taxpayers and our allocations through the ESA form just one part of this funding programme.”

Glasgow emerged as a satellite manufacturing hub thanks to a generation of Scottish space engineers returning home in the early 2000s, who — along with the universities’ space engineering courses — built expertise in the production of CubeSats, small and relatively inexpensive satellites generally made up of cube-shaped parts.

Malcolm Macdonald, a professor at Strathclyde university, urged the UK government to take more risks on longer-term programmes to develop the sector. “They need to move beyond grants to contracts, we could see more in terms of government placing contracts for the delivery of services.”

Edinburgh-based Skyrora, founded by Ukraine-born entrepreneur Volodymyr Levykin, this year became the first British company licensed to launch from SaxaVord.

Against the backdrop of the market dominance in the commercial launch sector held by Elon Musk’s SpaceX, Skyrora says it can be more of a “taxi service” to SpaceX’s “bus” for space operators.

Its launch vehicle would act as a “space tug” for satellites, refuelling, manoeuvring and then removing them from space, said Alan Thompson, head of government affairs. “That’s the business opportunity we are chasing — we don’t want to be competing on price per kilogramme with SpaceX, it’s just not sustainable.”

Near the UK’s most northerly point, SaxaVord Spaceport, located on a former Royal Air Force site, hopes to become the UK’s first vertical-launch spaceport next year with a planned test launch from the German start-up RFA, though some in the industry worry about poor weather conditions hampering regular operations.

Pitching itself as a launch pad for Europe’s growing space ambitions, driven by data services, SaxaVord is in talks with infrastructure funds to raise a further £50mn to construct two more launch pads and hangars required to bring the site to an operational capacity of up to 30 satellite launches a year, said chief executive Scott Hammond.

Like others in the industry, Hammond argues that government should offer financial assistance to launch companies to help them navigate the perilous first few launches, which commonly end in failure.

“It would not take lots of money to kick-start an industry which will create jobs. We are at that stage now, pump primed, to have a real vital industry.”

Read the full article here