Walking across the hilltop towards Artur Walther’s home in Upstate New York, you don’t so much see inside it as through it. The three intersecting petal-shaped segments of the building sit unobtrusively atop a rock ledge, the single wood-clad storey barely interrupting the skyline, while its wraparound glass allows you to see the views on the far side, across miles of woods, fields and valleys.

As one of the world’s leading collectors of photography, Walther has a refined sense of how to frame a scene. In his home there are few doors to interrupt the view. An expansive sofa is shaped like a woven nest, designed by Fernando & Humberto Campana for Edra — its undulating blue mass of cushions (which Walther says is “surprisingly comfortable”) offers views to the west over the Catskill Mountains. A little mist on the horizon hovers over the Hudson River. Behind, to the east, are The Berkshires.

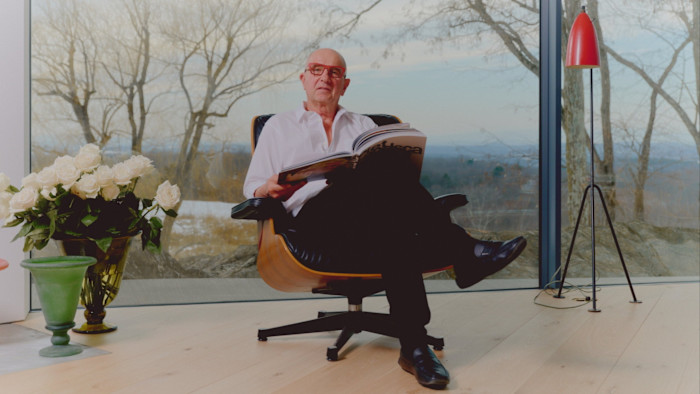

It was a radical change in career that brought him here, the former investment banker tells me, dressed casually in black jeans and an open-neck white shirt, offset by red-framed glasses. When he was in his mid-forties, “I got divorced, a lot of things happened, I decided to change my life.” And today another change is under way: he is stepping away from photography, donating much of his collection to museums and galleries, including 6,500 pieces to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. “The time is now,” he says.

Walther grew up modestly in Germany — his father was a lorry driver — but he came to the US to study at Harvard Business School and helped pioneer the fledgling derivatives market of the 1980s. He went on to become worldwide head of capital markets for Goldman Sachs. Despite success, he wanted more. “Life was very intense, but one dimensional. It was always the same clients, types of people, situations,” he says. “I was interested in other aspects.”

When he opened the new Goldman Sachs offices in Frankfurt in the early 1990s, just after German reunification, he surprisingly took charge of the interior design. Across three floors in the city’s tallest tower block, Walther rejected the partnership’s classic style in order to bring in contemporary furniture and photography. When he retired in 1994, aged 46 (to have “more time for myself”), and returned to the US, it was this area of interest he came back to.

He built a studio with a darkroom in New York’s Chelsea, attended classes at the International Center of Photography (ICP) and spent time with well-known photographers including Stephen Shore, Bruce Davidson and Mary Ellen Mark. He also turned to German photographers Hilla and Bernd Becher; some of their images of industrial architecture hang on his walls. “Their ‘new objectivity’ was close to my way of seeing,” he says. The couple introduced him to the work of Karl Blossfeldt; early 20th-century close-ups of plants are displayed in a group in his home.

It was Covid-19 that prompted him to retreat upstate to his country home, a 90-minute drive from the city. He had long owned a former dairy farm and, over the years, had acquired surrounding land to protect it from development. It was here he was able to build a new house. “I thought: if I don’t do it now, I never will.” Walther approached New York-based architects Solid Objectives Idenburg Liu, who used drone photography to map the landscape and shape the building to follow its curves. The design went through more than 100 iterations and adjustments.

Inside, the decor is considered and precise: there are the brightly coloured rectangles of Imi Knoebel’s collage sculpture “17 Farben, 20 Stäbe” and Kuno Gonschior’s abstract painting “Magenta”.

Although the white walls display a number of notable names and images, Walther’s collection has a depth and texture that constantly surprises. Just as many financiers entered “frontier markets” in the 1990s as the cold war ended, creating opportunities for freedom and innovation, Walther looked to unfamiliar areas to build his collection. “I was not looking at a western approach. I was interested in what had not been looked at, written about or researched,” he says. “I wanted to integrate non-western photography . . . I figured out what was interesting. I looked at series. I never bought one or two images. I bought 70 or 90.”

He was drawn at first to China and began acquiring works by figures including Ai Weiwei. “Until then, photography there was all propaganda. There was very little which dealt with social, historical, economic issues. I was there at the right time. The experience was amazing. Young artists were questioning everything,” he says. When it became “a hot market”, he stopped collecting. “It was too commercial. I didn’t want to do what everyone else was doing.”

He considered other regions including Latin America and India before settling on Africa. He embarked on a month-long research trip with the Nigerian curator Okwui Enwezor in 2003, visiting Morocco, Senegal, South Africa, Kenya, Ethiopia and Egypt. It inspired a subsequent exhibition: Events of the Self, work by three generations of African artists alongside modern and contemporary German photographers.

By 2011, he had converted a series of buildings in Neu-Ulm in Germany into a foundation and exhibition space, followed by the launch of the Walther Collection Project Space in New York. Eighteen catalogues from those institutions now sit atop his coffee tables. The Walther Collection has produced more than 50 exhibitions that have toured the world. Into the Unseen is currently on show at Deichtorhallen Hamburg.

But his mood has shifted. “I decided to be less involved. I wanted to give my collection to one or two institutions,” he says as he considers the photographs he no longer has.

Walther does, however, have a new passion: the outdoors. As we head outside, instead of a walk, we clamber into an open-sided Kawasaki off-road vehicle to explore the grounds he is remoulding. “I always liked to be hands-on,” he laughs as we set off at pace. “It gave me a certain way of seeing.” Caia, his German Shorthaired Pointer, circles us while somehow avoiding disappearing under the wheels. I cling to the roll bar as we plummet down steep gravel paths for a tour across fields and through woods.

He points out a guest house, describing plans for a residency studio for visiting artists. In several places on the summit he has scraped away quantities of topsoil to expose the underlying rock. He is experimenting with a vegetable patch and cultivating fungi on newly cut logs, as well as with beehives. Down the hill, he has built a small dam, which has reshaped the pond in which he regularly swims.

He pauses the car among the trees beneath the hill. “With age, I connect more with nature,” he says. “There is beauty in dead leaves, even their sound. With all the goofy, crazy things going on, we need to focus on what is real: the cycles in nature and self. I like to feel the light, heat, rain, breeze. To experience the wind. It’s a rupture and continuity with photography. You let go in a different way.”

Find out about our latest stories first — follow @ft_houseandhome on Instagram

Read the full article here