Receive free Petroleos Mexicanos updates

We’ll send you a myFT Daily Digest email rounding up the latest Petroleos Mexicanos news every morning.

Mexico’s injection of billions of pesos into state oil company Pemex to help it meet debt payments should calm markets in the short term, but does not address deeper issues at the indebted firm, analysts and bondholders have warned.

In its draft budget on Friday, the government for the first time set aside explicit financial support — worth 145bn peso ($8.2bn) — which will help Pemex meet $11.2bn in payments due next year on its $110bn debt pile.

The strategy allows Mexico to fund the company’s bond payments using cheaper sovereign debt. But while this may soothe the concerns of lenders in the short-term, investors and analysts cautioned that operational problems at Pemex demand fundamental reform. The company’s debt is in junk territory and in July rating agency Fitch downgraded it further while Moody’s put it on a negative outlook.

“This is the first time there is explicit support carved out for the company in the budget, which should help resolve market and (more importantly) credit rating agency concerns of the government being more reactive than proactive,” said Aaron Gifford, emerging markets sovereign analyst at $1.4tn-in-assets T Rowe Price — a Pemex bondholder.

“That doesn’t mean it’s going to be a silver bullet,” Gifford added. “There’s still a lot of issues that need to be resolved,” he said, pointing to the company’s negative free cash flow, a large capital expenditure budget and large tax payments to the Mexican government.

These problems are likely to attract deeper scrutiny as Mexico gears up for general elections in June 2024.

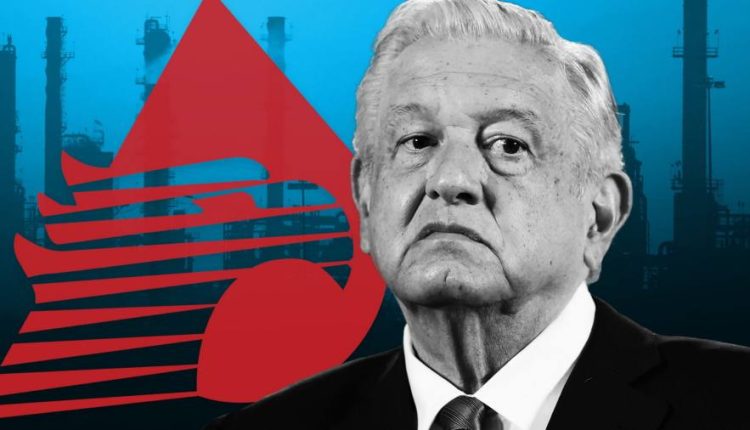

The change in leadership will bring fresh questions about the future of the state-owned company, which has relied heavily on governmental support under incumbent president Andrés Manuel López Obrador. Opposition candidate Xóchitl Gálvez told Bloomberg she would open the sector to more private investment, which the president rejects. Gálvez and the ruling party’s Claudia Sheinbaum — a former climate scientist — have both said they would accelerate the shift to renewables.

The oil nationalist López Obrador vowed to “rescue” Pemex and has given the company some 1.32tn pesos of financial help since taking office in 2018, according to data from think-tank Instituto Mexicano para la Competitividad (IMCO). Despite that, oil production has continued to fall and hit lows of 1.5mn barrels a day in 2022, down from more than 2.1mn b/d in 2016.

Some investors and analysts had anticipated direct governmental support for Pemex earlier this year. But the company instead issued a 10-year bond in February worth $2bn, with a yield of 10.375 per cent, relatively high compared to previous years.

The bond maturing in 2033 was priced at just over 91 cents on the dollar on Friday — well above a level of 70 cents typically seen as a signifier of distress.

But the bond’s yield has ticked up since issuance, in a reflection of its price falling — reaching more than 12 per cent in late August before moving back down to close out last week at 11.5 per cent.

At the same time, some of Pemex’s longer-dated bonds — including one maturing in 2050 — trade below 70 cents, hinting at investor uncertainty about the company’s longer-term future.

For the longer-dated bonds “to really perform, you need to have more of a wholesale solution for the company itself,” said a Pemex bondholder who did not wish to be named, speaking ahead of Friday’s draft budget announcement.

A capital allocation to Pemex in the budget helps with the short-term liquidity, the bondholder said.

“Maybe after the elections, there might be a more wholesale plan for the company put in place,” the bondholder added. “Or maybe there’s just more of this piecemeal [strategy].”

Experts have suggested reforms ranging from a significant reduction in its tax burden to stepping up investment in exploration and production to allowing more private companies to contribute.

Pemex said it has put itself on a path to a more solid financial footing, including by improving its refining capacity and exploiting new oil developments. It said in July that at constant prices in dollars its stock of debt is down more than 15 per cent since the end of 2018.

Old school leftist López Obrador had gained a reputation for fiscal conservatism in his five years in office, including refusing to provide significant economic support to people or companies during the pandemic and keeping the country’s debt levels below 50 per cent of gross domestic product.

But the extra money for Pemex on Friday came as part of a draft 2024 budget which estimated a deficit of 4.9 per cent of GDP — the highest since the 1980s.

Government spending has also been skewed towards bolstering state energy companies, López Obrador’s expansion of social programmes and a handful of mega projects in the country’s poorer south.

The ruling party Morena has simple majorities in both houses in its alliance, enough to pass the budget. But the next president will find money increasingly tied up in pensions, social programmes and projects leaving them little space for their own priorities.

Analysts expressed concern over the high deficit while the economy is already growing, which could leave them less money to counter an economic downturn or if oil prices fall, said Carlos Serrano chief economist at BBVA Mexico.

“If in 2025 the oil price falls, they aren’t going to have the capacity to react or they will have to adjust spending in a way that hurts the economy,” he said.

Barclay’s economist Gabriel Casillas was more sanguine about the 2024 budget’s implications for the economy and the next leader, except in the case of Pemex. “In my view, all fiscal issues can be solved rather easily, except Pemex,” he said.

He said the government had muddled through with financial help for Pemex and despite the company’s efforts on environmental, social and governance metrics (ESG) it still lagged global peers. “Pemex needs to be tackled structurally,” he said.

Read the full article here