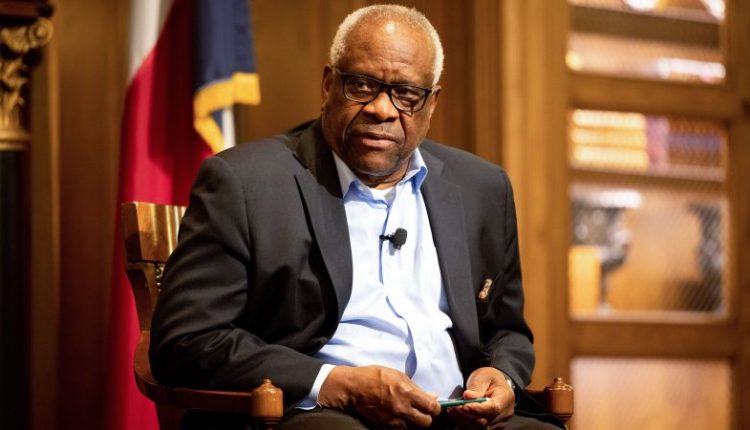

Long before he became a Supreme Court justice, Clarence Thomas told a story at a public gathering that still sounds shocking years later.

At the time, Thomas was a relatively unknown conservative who had paid his way to attend a conference of Black conservatives just before Ronald Reagan entered the White House in 1981. At the conference, Thomas told listeners that he opposed public assistance because it had caused his sister and her children to become dependent on welfare payments.

“She gets mad when the mailman is late with her welfare check,” Thomas said in a remark that has since been widely quoted. “That is how dependent she is. What’s worse is that now her kids feel entitled to the check, too. They have no motivation for doing better or getting out of that situation.”

But a journalist tracked down Thomas’ sister and discovered that what he said about her was not quite true. She learned that while Thomas attended law school, his sister Emma Mae Martin worked two minimum-wage jobs before quitting to take care of an ailing elderly aunt. She did receive welfare checks, but their sums were paltry, and she later took another job as a hospital cook. And her children all either worked or were in school when the journalist spoke with her. One even served his country aboard a battleship during Operation Desert Storm.

Thomas’ story has taken on new meaning since ProPublica and other media outlets revealed he’s been the beneficiary of another type of assistance: The lavish lifestyle the justice has enjoyed over the last three decades has been bankrolled in part by wealthy White benefactors.

Thomas disclosed last month week that Republican Texas billionaire Harlan Crow paid for private jet trips for him in 2022 to attend a speech in Texas and a separate vacation at Crow’s luxurious New York estate.

Thomas also acknowledged he had “inadvertently omitted” other information in past financial disclosure reports, including a private real estate deal between Crow, Thomas, and Thomas’ family. Crow, who paid the private school tuition for a relative of Thomas he said he was raising “as a son,” also purchased the home of Thomas’ mother in a private real estate deal that allows her to live rent free.

The disclosures about Thomas have set off a debate among judicial ethics experts. Critics say Crow’s largesse is part of a pattern of Thomas taking undisclosed gifts from “fawning” billionaires who benefit from his legal decisions.

A lawyer for Thomas said there had been “no willful ethics transgressions” by the justice, and attributed the criticism to “political blood sport.”

But the latest revelations about Thomas may also have another unintended effect: They should put the to rest the myth about why so many Black people have despised Thomas going back to his days in the Reagan administration, when he chaired the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

The myth is that many Black people oppose Thomas because they can’t handle his stern calls for self-reliance and his admonishments to stop looking for free stuff from White people or government programs. According to the conventional story, Black people don’t like Thomas because he is a Republican and a conservative—and because, according to Thomas in a fiery 1998 speech, he refused to be an “intellectual slave.”

But many Black people don’t despise Thomas because he’s a conservative. They reject him because they say he’s a “hypocrite” and a “traitor” who hurts his own people to help himself.

Georgia State Senator Nikki Merritt is one of them. The Democrat says recent revelations about Thomas benefitting from wealthy White benefactors validated what she and others have been saying about the justice for years. She was one of several Black members of the Georgia Senate who opposed a bill last year to erect a statue in honor of Thomas.

Merritt says that many Black people don’t have a problem with conservatives or Republicans. The late Colin Powell and Condoleezza Rice both served in Republican presidential administrations as Black conservatives. Both are well-respected in the Black community.

But Thomas, she says, is something else. Merritt says he actively hurts his own people by consistently voting to weaken voting rights and helping to overturn Roe v. Wade, a decision she says disproportionately hurts poor women of color.

“Justice Thomas likes to talk about the myth of pulling himself up by his bootstraps and being resilient, yet he’s benefited from handouts from these White conservatives who have supported his privileged lifestyle,” she says. “That makes him a traitor and a hypocrite in my eyes.”

Black hostility toward Thomas has had a long shelf life, and has spilled out into the public in different ways. The NAACP opposed his 1991 nomination to the Supreme Court. Anita Hill’s sexual harassment allegations against Thomas, which came during his confirmation hearings, irreparably damaged his reputation among many Black women.

When the National Museum of African American History and Culture opened in Washington in 2016, its organizers excluded any direct mention of Thomas in the exhibits. Various Black leaders have called Thomas an “Uncle Tom,” and the NAACP’s current president recently called Thomas “the worst thing” affirmative action created. It’s telling that Juan Williams, the journalist who was once one of Thomas’ most vocal defenders in the Black community, now says that Thomas must be sanctioned if the stories are true about how he allowed himself “to become captive of a far-right legal coterie.”

Others, though, see Thomas as an American hero, an embodiment of the idea that anyone can make it in America if they work hard enough.

Armstrong Williams, a Black conservative, said that the recent criticism aimed at Thomas has degenerated into “hysterical verbal pummeling.” He said that other Supreme Court judges took subsidized trips in the past, but critics focus on Thomas because of his intellectual independence.

“Their real grievance against the justice is his courageous unwillingness to shill for the liberal establishment — an insult they find especially offensive because Clarence Thomas is black and contradicts their gospel that all blacks think alike,” Williams wrote in a recent column.

One federal judge, a Republican appointee, defended Thomas against charges he was being influenced by wealthy, White donors.

“Judges are just like every other human being. We have a diverse group of friends, and those friends don’t influence the way we do our job,” Judge Amul Thapar, who sits on a Cincinnati-based appeals court, told CNN in an interview.

The Supreme Court’s press office did not respond to a request seeking comment from Thomas or the high court about the justice’s actions or his relationship to the Black community.

But Thomas has briefly addressed the issue, saying he followed the advice of others who told him he was not required to disclose the gifts.

The justice noted that the guidelines for reporting personal hospitality were recently changed and added, “it is, of course, my intent to follow this guidance in the future.”

Thomas’ former law clerks also have defended him. Last month more than 100 of them published an open letter saying Thomas’ “integrity is unimpeachable” and describing him as an embodiment of the American dream as a descendent of enslaved people who worked his way up to the pinnacle of judicial power.

They declared that Thomas’ story “should be told in every American classroom, at every American kitchen table, in every anthology of American dreams realized.”

But critics within the Black community say Thomas doesn’t practice what he preaches — and they’ve been saying this long before recent disclosures about the justice’s benefactors.

Some point to his opposition to affirmative action, a set of policies designed to boost minority representation in education and the workplace.

Thomas says affirmative action policies are divisive, unconstitutional and harmful to recipients. He recently voted with the high court’s conservative majority to gut affirmative action in college admissions, overturning a long-standing precedent.

But his critics say Thomas would not have made it on the high court without affirmative action. They say he was admitted to Yale Law School because of an affirmative action program and that he was nominated to the Supreme Court to replace Thurgood Marshall, the court’s first Black justice, in part because of his race.

“His entire judicial philosophy is at war with his own biography,” Michael Fletcher, co-author of “Supreme Discomfort: The Divided Soul of Clarence Thomas,”. told CNN in 2013. “He’s arguably benefited from affirmative action every step of the way.”

Thomas has admitted that he was accepted at Yale Law School under an affirmative action policy. In his 2007 memoir, “My Grandfather’s Son,” he wrote: “As much as it stung to be told that I’d done well in the seminary despite my race, it was far worse to feel that I was now at Yale because of it.”

Thomas’ critics have long accused him of hypocrisy in another area: how he talks about self-reliance.

The contours of Thomas’ early life are well-known. He was born in the segregated South and grew up in grinding poverty in rural Georgia. He was rescued by a stern but loving grandfather who taught him the virtues of self-reliance.

Thomas flirted with Black nationalism in college, wearing a black beret and memorizing the speeches of Malcolm X, before graduating and gradually becoming a conservative and a Republican.

Thomas himself has reinforced this narrative. He often invoked stories of rugged self-reliance in his earliest interviews and in his 2007 memoir, “My Grandfather’s Son.”

In 1987, Thomas said he was raised in an environment where “you had an obligation to help other people, but it didn’t come from the government.” He criticized civil rights leaders who he said were teaching Black kids that getting ahead in America was hopeless because of pervasive racism.

“They should be telling these kids that freedom carries not only benefits, it carries responsibilities,” Thomas said. “You want to be free, you want to leave your parents’ house? Then you’ve got to earn your own living, you’ve got to pay your own mortgage, pay your own rent, buy your own car, and pay for your own food.”

But Thomas’ critics point to what they say are contradictions in his biography.

After disclosures about the financial help Thomas received from White benefactors went public, his critics pounced.

A headline from The Grio, a Black online magazine, read: “Clarence Thomas gets gifts from a white billionaire but hates white paternalism.”

Another from The Nation, a self-described progressive magazine, read: “Clarence Thomas Is What He Wrongly Accuses Black Folks of Being.”

Tori Otten, a writer with The New Republic, highlighted Thomas’ criticism of his sister from many years ago, saying his comments were “particularly hypocritical, considering how often he has claimed to be against government aid and welfare.” Otten added, “But Thomas and his family have spent decades enjoying free travel, housing, and school that are only offered because he holds a powerful position in the government.”

Juan Williams, a Black journalist who says he and Thomas are friends, also criticized the justice. In a 2022 column before the disclosures about Thomas’ gifts, he mentioned Thomas’ wife, Virginia “Ginni” Thomas, and her support of former President Trump’s attempt to reverse the 2020 presidential election results. She emailed lawmakers in Wisconsin and Arizona, asking them to “fight back against fraud” by helping overturn the vote.

Williams didn’t use the word “hypocrisy” to describe Thomas. He says there are “contradictions.”

“As a young man he was a Black nationalist, able to recite Malcolm X speeches,” Williams wrote. “Now, at 74, he surrounds himself with far-right white conservatives and is married to a white woman who sought to help a man viewed by most Black people as a racist — Trump — overturn a legitimate election.”

Williams, like other Black writers, notes that Thomas stands in the tradition of other Black nationalist leaders who preached self-reliance. Some of Thomas’ beliefs echo revered Black leaders such as Booker T. Washington, Marcus Garvey and Malcolm X. All preached some variation of self-help and not looking to White people for deliverance from racism.

Even President Obama has delivered speeches that don’t sound that different from Thomas. In a 2013 speech to graduates of Morehouse College, a predominantly Black men’s college in Atlanta, Obama said that excuses are “tools of the incompetent.”

“We’ve got no time for excuses – not because the bitter legacies of slavery and segregation have vanished entirely; they have not. Not because racism and discrimination no longer exist; we know those are still out there,” he said. “It’s just that in today’s hyperconnected, hypercompetitive world, with millions of young people from China and India and Brazil – many of whom started with a whole lot less than all of you did… nobody is going to give you anything that you have not earned.”

Yet Williams pinpointed in a recent Atlantic magazine essay what separates Thomas from Black nationalist leaders who preached self-help.

“Thomas similarly argued that Black people could demonstrate their abilities only if white people got out of their way, and stopped pursuing programs such as affirmative action,” Williams wrote.

“However, the big difference between Thomas and most Black nationalists is that he assures whites that they have no responsibility for the history of slavery and continued bias.”

Thomas has consistently ruled against civil rights programs that attempt to address the legacies of slavery and Jim Crow segregation on behalf of Black people. He called such programs “racial tinkering.” He also has drawn a moral equivalence between schools that created programs to encourage racial diversity and White schools in the Jim Crow era that banned students of color.

Thomas has said that programs designed to make up for racism are demeaning and patronizing to Black people – and unconstitutional, because the Constitution is “colorblind.”

“I do not believe that kneeling is a position of strength,” Thomas reportedly said in a 1998 speech while talking about affirmative action. “Nor do I believe that begging is an effective tactic.”

He once quoted the 19th century abolitionist Frederick Douglass, who responded to the question of what the American people should do with Black people by saying, “Do nothing with us!… If the negro cannot stand on his own legs, let him fall also.”

When he worked for the Reagan Administration, Thomas said all civil rights leaders do is “bitch, bitch, bitch, moan and moan, whine and whine.”

But in 1998, Thomas showed a more vulnerable side in an address before the National Bar Association, a predominantly Black group.

“It pains me more deeply than any of you can imagine – to be perceived by so many members of my race as doing them harm,” he told the group. “All the sacrifice, all the long hours of preparation were to help, not to hurt.”

Thomas’ speech was greeted with scattered boos and little applause, news reports said.

The recent disclosures about Thomas’ bankrolled lifestyle have been greeted by some Black people in another way—by nodded heads and a string of “I told you-so’s.”

Merritt, the Georgia state senator, says calling Thomas a traitor and a hypocrite is fitting criticism because of the impact of his judicial decisions.

“He claims he’s a Black man that cares about Black people and Black causes, but every action that he has taken has done nothing but harm Black people,” she says.

So maybe now the myth about why Black people oppose Thomas will finally die.

For many Black people, the speech that Thomas gave about his sister was not an aberration but the start of a pattern: Thomas projects onto Black people what he refuses to see in himself. As one critic said:

Thomas, not his sister, is the “true welfare queen.”

Read the full article here