In 2006, while managing an impact venture capital fund at JPMorgan Chase, Nancy Pfund decided to invest in a clean energy start-up that was developing electric vehicles. Colleagues were sceptical. Would electric cars, they asked, really transform the auto industry? No, was the consensus. But today, almost one in five cars sold globally is electric. And the name of the start-up? Tesla.

For Pfund, who in 2008 founded impact-focused venture capital firm DBL Partners (taking the venture fund with her), Tesla’s trajectory offers striking evidence that investments intended to bring about positive social or environmental impact can perform well financially. “Impact investing has the potential to catalyse systemic change,” says Pfund. “And it’s not on the margin — it’s part of the business opportunity.”

Back when Pfund was making her bet on Tesla, impact investors tended to be philanthropists deploying “catalytic capital” — investments that, in return for social impact, came with lower-than-market-rate returns or meant accepting higher risk for longer periods of time.

This is still how many see impact investing. “That’s the massive cultural hurdle,” says Sarah Gordon, a former Financial Times business editor and a visiting professor in practice at the London School of Economics’ Grantham Research Institute. “The overwhelming perception still is that impact investing is by nature concessionary.”

Even so, more investors are developing impact investing strategies that they believe can deliver market-rate returns. The Global Impact Investing Network now puts the value of investments whose purpose is to make a positive impact and a financial return at more than $1.57tn globally, after compound annual growth of 21 per cent since 2019.

Impact investments are generally seen as those targeting enterprises or funds whose explicit purpose is to make a positive impact, unlike those made using an environmental, social and governance lens, which screen out companies with high ESG risks or focus on companies that can show they are improving their societal footprint.

Impact investing’s growth comes as ESG funds have started falling out of favour. Outflows from ESG funds have arisen partly from a US political backlash against “woke” capitalism and partly as a result of weak financial performance by many clean energy companies amid higher interest rates.

However, concerns have also been growing that ESG strategies do more to de-risk investment portfolios than to promote sustainability. A focus on risk screening can, for example, lead to excluding companies in emerging markets or in transition sectors such as energy, where many opportunities for impact exist. “I’d argue that ESG risk screening delivers the opposite of positive impact in many cases,” says Gordon.

Jennifer Pryce, chief executive of Calvert Impact, a non-profit investment firm, points to one way in which the ESG fallout has been helpful. “It did educate the market that impact investing is something different,” she says. “There’s a lot more understanding that, at its core, impact investing is thinking about investment for solutions.”

Impact investing has some way to go before it reaches the scale of ESG-focused investments, which were worth more than $30tn in 2022, according to Bloomberg. While ESG funds have been active investors in publicly listed equities and bonds, impact strategies have been deployed primarily in the much smaller private markets.

“I find this a bit frustrating,” says Maria Teresa Zappia, deputy chief executive and chief impact and blended finance officer at Schroders’ impact investing arm BlueOrchard, which has been developing listed debt and listed equity impact strategies with a select group of fund managers at both BlueOrchard and Schroders.

“Even with a strict selection process on the impact side, there is an investment universe [in public markets] that is diversified and has all the bells and whistles that impact investors are looking for,” says Zappia, who is also global head of sustainability and impact at Schroders. “Listed equities are where we need to go next.”

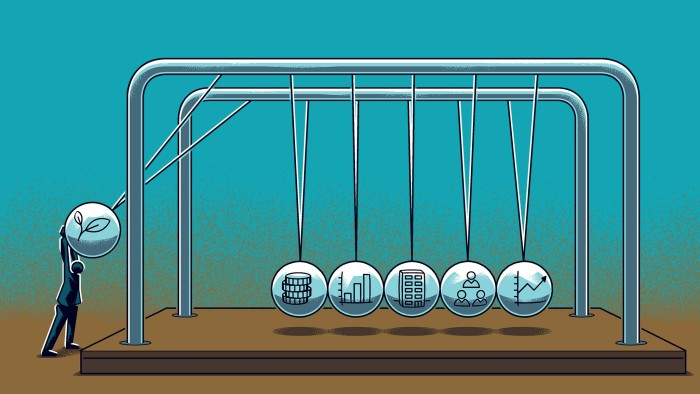

With barriers ranging from perceptions of risk to lack of measurement metrics, this will be easier said than done. Yet there is a growing sense that moving the needle on sustainable development will require going beyond growth in the impact investing market itself.

“It’s not that there’s no future for pure impact investing,” says Gordon. “It’s more that impact investing concepts need to be integrated more successfully into mainstream investing.”

Putting impact into words

Among the factors Erika Karp believes is hampering broader adoption of impact investing is a divergence in definitions. “Some believe every investment has impact, which engages the public markets, and some think that by definition [impact investment must be] catalytic,” says Karp, founder of Cornerstone Capital, now part of family office investment adviser Pathstone. “The problem with the former is you have the issue of greenwashing. The problem with the latter is that it’s very hard to scale.”

Karp is not alone in finding the language surrounding impact investing unhelpful. For Gordon, the very word “impact” can be exclusive rather than inclusive, placing the investment approach into a silo. “The biggest barrier to impact investing is people thinking it’s a side hustle, something you do on top of the main event, which is your investing,” she says.

Of course, for those analysing the size and state of the market, coming up with a definition is unavoidable. To be included in the GIIN’s data set, for example, organisations must demonstrate an intent to create positive environmental or social impact and show that they are seeking a financial return and measuring the results of their investments.

Impact investors also aim to achieve “additionality” — that is, they should be able to show that their positive societal impact would not have been possible without the company’s products or services or the capital supporting its growth.

Dean Hand, GIIN’s chief research officer, sees this as impact by design, not by default. “Any investor is going to have an impact of some sort,” she says. “We’re isolating the investments that are intentionally trying to do that.”

Not everyone worries about such distinctions. With a dual mandate of maximising financial returns for its 6mn pensioners while supporting economic development in Canada’s Quebec province, the $330bn pension fund CDPQ uses the term “constructive capital”.

“We don’t position ourselves as an impact investor per se. That’s not the terminology we use,” says Yana Watson Kakar, managing director and head of Americas at CDPQ. “But impact investments are made with the intention of generating measurable positive social and environmental impact — that’s us.”

A place for the purists

With a $16bn endowment, the Ford Foundation has more money than most to spend on changing the world. And for much of its history, its endowment was invested to generate a financial return that could pay for grantmaking and operational costs. But in 2017, the foundation made an announcement: it would use $1bn of its endowment to seek “concrete social returns” as well as financial returns.

Aside from its sheer size, Ford’s commitment was similar to those of the many philanthropists and foundation executives who at the time were making investments that would deliver lower-than-market rates of return but greater social or environmental impact than a philanthropic grant.

It’s a practice that continues to thrive, particularly as many ultra-rich young people inheriting family wealth seek to define themselves as impact investors rather than as philanthropists, and as more foundations have followed Ford’s example by tapping into their endowments to make “mission investments” that advance their philanthropic goals.

While it is only a tiny slice of the sustainable investment market, many see this catalytic capital as playing an important role. “It’s absolutely critical,” says Bella Landymore, co-chief executive of the UK’s Impact Investing Institute. “Some activities that need funding are never going to be fully commercial.”

Many of these types of impact investors also use their investments to bring others on board. In 2017, the Ford Foundation made this clear. “The move sends a signal to other foundations and institutional investors that perhaps the time has come to consider the potential of impact investing,” it said in announcing its $1bn commitment.

Catalytic capital often helps fill funding gaps for projects that, because they are in emerging markets, are in challenging political environments or involve technology risk, are seen as too risky by mainstream investors.

“That type of risk-taking, boundary-pushing philanthropy needs to keep at it,” says Georgia Levenson Keohane, chief executive of the Soros Economic Development Fund at the Open Society Foundations. “Because there is so much it can do that the more commercial field can’t.”

Liesel Pritzker Simmons — a member of the billionaire Pritzker family, which made its fortune through the Hyatt hotel chain — highlights the constraints facing some mainstream investors, particularly pension funds. “Their job is to keep safe and increase the value of the hard-earned dollars of pensioners,” says Pritzker Simmons, whose Blue Haven Initiative family office makes both market-rate and catalytic impact investments. “Where something has too much risk or a slightly lower return as a market is being built, let’s use philanthropic capital.”

In addition, says Landymore, investors who are prepared to take lower-than-market rates of return can help bring commercial investors to the table. “It’s providing that runway, that first loss and buffer through risk mitigation tools so other private capital can crowd in,” she says. “That’s where it’s most needed.”

An expanding investment universe

As impact investing has made its way into the commercial corners of the capital markets, its growth has been most rapid in private asset classes, with venture capital and private equity offering opportunities for impact investors to build portfolios of high-growth companies.

Today, some of these portfolios have large amounts of assets under management. DBL Partners, for example, manages more than $1bn while private equity giant TPG manages $25bn of impact-oriented capital in its Rise, Rise Climate and Evercare Health funds.

Lyel Resner, an MIT visiting faculty member, sees growing opportunities for impact-focused venture capital investments in tech founders who are using an alternative to the typical Silicon Valley model to build their companies. “It’s a different set of skills from the move-fast-and-break-things approach,” he says. “And the good news is that there are plenty of people who are moving with intention, building trust and creating exceptional companies.”

Real estate is another asset class that can lend itself to impact investing. According to Better Society Capital (the UK social impact investor formerly known as Big Society Capital), the highest concentration of impact investments by UK pension funds — which BSC says make up 21 per cent of the country’s impact investors — is in social and affordable housing.

LSE’s Gordon argues that what she calls “place-based impact investing” can improve lives in specific underserved regions while offering market-rate returns for institutional investors. “We need decent, affordable housing so children aren’t living in poverty,” she says. “The housing problem is an impact problem.”

For now, impact investing allocations to public equities are small, at 7 per cent of total assets compared to the 43 per cent of impact funds allocated to private equity, according to 2024 GIIN data.

Even so, this may be changing. When we asked FT Moral Money readers which asset classes were best suited to impact investing, venture capital topped the list, at 36 per cent of respondents. But while private equity ranked second at 27 per cent, so did public equities, also at 27 per cent.

GIIN’s Hand sees a shift emerging in the data. “The volume of capital allocated to listed asset classes is growing at a far faster rate over a five-year period than the allocations to private markets,” she says.

In data the GIIN collected from more than 300 organisations in the first three months of 2024, large investors managing more than $500mn in assets held 92 per cent of the total assets held by the 300 organisations surveyed.

Hand also sees large investors such as pension funds beginning to seek not only to boost the retirement income of their members, but also to use their investments to help members to retire in a more equitable and environmentally sustainable world. It is, she says, a new focus on “changing the context that may affect their beneficiaries down the line.”

Putting a number on impact

Among the barriers to impact investing that FT Moral Money readers picked, a lack of metrics for assessing positive social or environmental impact ranked second, at 30 per cent of respondents.

Calls for better measurement tools and increased transparency have long been heard across the sustainable finance landscape. Yet Gordon says that much has changed since 2019, when she entered the world of impact investing. “In the five years since then we’ve made incredible progress on transparency and standards,” she says. “This could move quite quickly.”

Some of that progress has been the result of collective efforts. For example, between 2016 and 2018, the Impact Management Project brought together more than 3,000 companies and investors to hammer out consensus on how to measure and disclose both positive and negative impact.

Other efforts have taken place in-house. TPG’s approach to measuring impact as rigorously as financial returns was to develop Y Analytics, a system that uses data, evidence and third-party research in its impact assessments.

As well as the ability to measure impact, BlueOrchard’s Zappia says that demonstrating correlations between positive impact and financial performance will be critical to expanding impact investing practices across mainstream markets. “There is interest in new asset classes,” she says. “But the elephant in the room, which is financial performance going hand in hand with impact, is still there.”

For this reason, BlueOrchard is working with Oxford university’s Saïd Business School to track the relationship between impact and financial performance across its portfolio, starting with listed equities. “Preliminary results show a positive correlation,” says Zappia.

More and better data could also help solve a problem identified by Pryce of Calvert Impact: a lack of nuance in the market. “Different impact investors have different types of profiles,” she says. “Some are longer-term, some shorter-term, some carry more risk and need a higher return, some take on lower risk so should carry a lower return.”

In Pryce’s view, the absence of differentiation between different types of impact investors is another factor leading to the focus on whether or not impact investing delivers market-rate returns. “It devolves into a binary conversation,” she says.

Priya Parrish, chief investment officer at Chicago-based Impact Engine, whose venture capital and private equity investments target market-rate returns, also sees the need to identify nuances in impact investing. “There are funds out there that are not targeting market rate on purpose because there’s a quantity of impact that would not be possible at market rate returns,” she says. “That may not be appropriate for all institutions, but it is for some.”

Moving to the mainstream

If impact investing is having a moment in the sun, a future where an impact lens is applied to all investments remains some way off. And among the obstacles are two factors commonly cited as hampering efforts to push all private capital in a more sustainable direction: the relentless focus of investors on short-term profits and lack of regulatory signals.

When we asked FT Moral Money readers what they thought was holding back impact investing, the focus on short-term gains over long-term value topped the list, as did the failure of regulation to force appropriate pricing of negative externalities. Some 40 per cent of respondents pointed to both as key barriers.

Worries over policy gaps unite many advocates of more sustainable capital markets — including impact investing. “The pricing in of externalities is fundamentally a regulatory challenge,” says Gordon. “At the moment a positive impact is seen as extra and meanwhile all these companies are not paying for their negative externalities.”

Blue Haven’s Pritzker Simmons agrees. Real progress, she argues, cannot be achieved through the voluntary efforts of the private sector. “For a very long time businesses have not had to pay for the messes they make,” she says. “The world cannot afford to subsidise this kind of sloppy accounting.”

Prospects for global government action on these issues have taken a knock as a result of Donald Trump’s US election victory, given that he has strongly opposed tighter environmental and social regulations on business.

Government intervention aside, some argue that applying an impact lens to all investing requires a shift in mindset from asset allocators. “It’s not a niche pursuit or a carve-out,” says Landymore of the Impact Investing Institute. “It’s a more expansive view of risk and a more intentional approach to creating opportunities.”

Read the full article here