Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Earlier this year I had one of those encounters which, afterwards, I just couldn’t stop thinking about. Eight months and some digging later, I have decided to write about it.

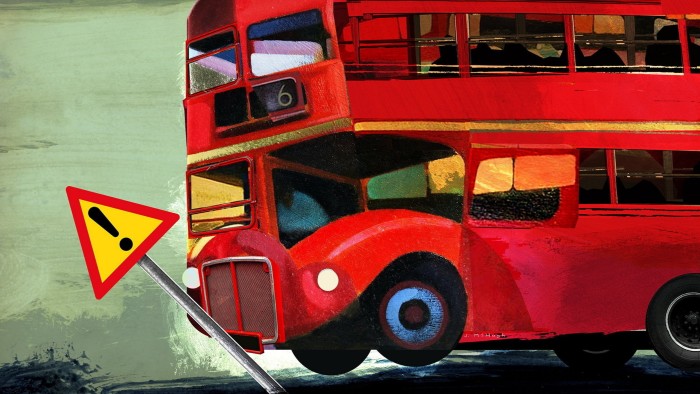

My meeting was with an American businessman called Tom Kearney, who was on a pavement in central London one Christmas when he was whacked on the head so hard that he fell to the ground, spent weeks in a coma, and only just survived. Had he been mugged? Not quite. He’d been hit by the giant wing mirror of a London bus.

Accidents do happen, however tragic. That was my first reaction. But as a mining executive who knew a thing or two about safety procedures, Kearney didn’t like the way the authorities reacted when he started researching from his hospital bed. What he found has turned him into a tireless campaigner against what he believes are systemic safety failures.

The most recent data show that 86 people died or were badly injured in bus collisions in London between 10 December 2023 and 31 March 2024. Kearney’s analysis of TfL data suggests that around three people a day are hospitalised after bus safety incidents. That doesn’t feel good, even though it’s tiny in comparison to the 1.8bn annual passenger journeys. Compared with other world cities like New York and Paris the capital’s buses rank in the top quartile for financial efficiency but the bottom quartile for collisions per kilometre. And the number of collisions in London has increased in the past couple of years, despite buses travelling fewer miles.

Could this have anything to do with the way that bus contracts prioritise speed? Last week, hundreds of bus drivers marched to TfL headquarters to demand better working conditions and the right to report safety concerns “without fear of retribution from TfL or employers”. Drivers described the pressure of long shifts, few breaks and having to drive in sometimes blistering heat, all while being shouted at over a monitor by controllers who want them to make up the time to the next stop, and keep the right amount of distance between their bus and next. It’s not surprising that a third of bus drivers, before the pandemic, reported having had a “close call” from fatigue.

With the government about to export the London franchise model to other parts of the country, someone in Whitehall needs to take a look. Michael Liebreich, a former McKinsey consultant who sat on the TfL board for six years, believes that TfL’s contracting out model is “institutionally unsafe”. Bus drivers are under such pressure, he thinks, that some may break the speed limit and overtake cyclists dangerously.

I still wasn’t sure about this, until I met the families of more victims. Katrina Finnegan’s aunt Kathleen died earlier this year, after being hit by a bus at Victoria bus station. Trish Burr’s daughter Melissa also died in Victoria a few years earlier, after a driver accidentally hit the accelerator.

What shocked me was how badly the families were treated. Katrina did not receive any immediate communication from TfL or the bus company — an experience reported by other victims. Trish’s grief was compounded by a false claim, from TfL’s safety committee, that Melissa had put herself at risk by walking between buses. TfL finally apologised for this error two months ago. But blaming the victim seems quite common. Sarah de Lagarde, horrifically injured after she fell on to a Tube track, was accused, incorrectly, of having been drunk. A TfL summary list of bus fatalities provides explanations which absolve the driver in a number of cases, before any inquest has been held.

Accurate data is hard to obtain. In 2020, TfL changed its definition of “serious injury”. It stopped including every victim taken to hospital and favoured a narrower definition, which only logs impacts like bone fractures, loss of a limb or loss of consciousness. It may perhaps be legitimate to exclude people who were taken to hospital only as a precaution. But it also blurs the picture.

Understanding the scale of the problem is made harder by the fact that few victims are named, so survivors who would like to compare notes can’t find each other. Sometimes you get a story in a local paper. So we know, for example, that the day after Kathleen Finnegan was killed, four passengers were injured when a bus at Earl’s Court hit a building. We also know that a woman was seriously injured after being hit by a bus in Lewisham around the same time and two children were hit by a bus in east London.

But we don’t know who they were. It’s only when a tragedy reaches epic, heart-rending proportions that a victim is named. This August, a nine-year-old girl was killed in Bexleyheath by a double decker bus which veered off the road while she was cycling along a pavement. Her five-year-old brother was injured but survived. Ada Bicakci’s parents donated her organs to six other children.

Was Ada’s death preventable? Are these all individual tragedies, or is there a systemic problem? This is an issue that falls between the local and the national. It involves complex procedures, where lessons are always said to have been learnt but where little seems to change.

As drivers, survivors and experts come together, Kearney reminds me of James Titcombe, whose baby died in Morecambe Bay hospital in 2008 and whose dogged questioning exposed a scandal. Titcombe also knew about safety, having worked in the nuclear industry. Kearney combines his board directorships of industrial companies with relentless campaigning. I wouldn’t bet against him.

Read the full article here