I’m standing in the industrial wasteland of Grimsby docks. Between the voids where warehouses once stood and the wharves where a vast fishing fleet once landed is Alfred Enderby, one of the very finest artisanal cold-smokers of fish in the country. I’ve come to pick up a box of Finnan haddock. These aren’t just “smoked fish”, they’re lightly smoked, on the bone, in a way that subtly enhances the delicate flavour of our finest sea fish, through the carefully modulated smoking process.

It’s the kind of product that most countries would shout about to the world. Handmade, in small batches, from the freshest ingredients, by a process going back centuries. This is what happens if you take the best from our seas and treat it like a world-class single malt. I am here because, for some months now, I have been thinking about fishcakes — their many pleasures, but also their formal limitations. Their reputation for stodge. In fact, I have a horrible feeling that it is Americans rather than the British who are getting this genre right. If we’re going to do a British fishcake to be proud of, Alfred Enderby’s is the starting point.

The fishcake is an iteration on the theme of “fried-balls-of-bits-and-filler” which most cultures have but which Britain has executed poorly. It must have been some sort of Orwellian ministry who decided to co-opt the rissole; a uniquely miserable preparation, impossible to love by anyone who doesn’t have a canteen of hungry people to feed on rations and a tight budget. I remember them made of leftover beef, corned beef, spam and something that was supposed to have been chicken but tasted like it had been passed through a fox. But even the most hardened denier of the fried-puck idiom would perk up when fish entered the equation. Fishcakes are different. There is joy to be had in them. They somehow don’t feel parsimonious. They’re even a bit — whisper it low — “posh”.

The fishcake is a British classic despite the fact that we don’t have a great native tradition of fish canning. When we still caught sardines in quantity on our coasts, they were usually salted and packed into barrels to be shipped to the cities. Much canned fish was imported. Most of our tinned sardines came from Spain and Portugal, a cheap protein that didn’t need complicated cooking. Though they’re agonisingly hip today, for most of the past century they were a convenience food. A basics-range ready meal avant la lettre. But canned salmon that came over from the outpost of empire, the Canadian wild, was different. A bit of luxury. And sometimes an affordable one. You might not have turned it out on to a plate by itself at dinner, but in a sandwich, crumbled into a salad or stretched with potato into a fishcake, salmon wasn’t half bad. If you weren’t the kind of family quite able to afford the smoked salmon from the posh grocers, you could definitely pick up a tin of the imported stuff and enjoy it almost as much.

Which is how the salmon fishcake entered the British canon, laden, as foods almost invariably are with baggage of class and empire, and why, when the British restaurant renaissance took off in the 1990s, it suddenly resurfaced, ripe for ironic reinvention. The new “foodies”, indoctrinated in the superiority of continental cuisines, sought things that would represent our own heritage. They looked to the recipes of their childhood, of institutions. It’s easy in hindsight to characterise the trend as a misty-eyed nostalgia for “nursery food” but it was rooted in a real need to explore our own culinary identities. Salmon fishcakes, with poached not tinned salmon and a classic French sorrel sauce, cropped up all over the place. They were on the menu at The Ivy. They were a signature at Le Caprice from the day it opened and are still served proudly at Arlington on the same site.

The original British fishcake

To make four

I still occasionally use the classic combination of tinned fish and leftover mash, but in the recipe below I’ve also given a few alternatives as one ought to improvise with this sort of thing. A basic fishcake is made of leftovers and store cupboard staples and that principle still holds. We just have more exotic leftovers and better-stocked store cupboards today.

-

200g of one of the following: leftover poached salmon; supermarket “hot-smoked” salmon or trout; tinned salmon; intensely fashionable, artisanal Portuguese tinned sardines, drained and mashed. (Any pre-cooked fish is worth considering, including crab.)

-

200g mashed potato — either made fresh, with leftovers or from tinned potatoes. (You can’t use reconstituted powdered mash . . . we’re not barbarians.)

-

Your secret ingredient: capers, fresh tarragon, piccalilli, chopped gherkin, frozen peas, hot sauce, crushed Scampi Fries — to taste.

-

An egg

-

Panko breadcrumbs

Put all the ingredients except the panko breadcrumbs in a bowl and combine, not too fussily. Season heavily with your secret ingredient. I suspect fishcakes were always a little nesh and early recipes often added “anchovy essence”. These days you’ll probably have nam pla in your larder if fishiness is your preference. Personally, I lean heavily into fermented chilli hot sauce. Whatever your secret ingredient, remember that everything is already cooked, so “to taste” means “keep tasting until you’re delighted”.

Form into patties and coat in the breadcrumbs. Shallow fry, browning on all sides, and then give them 10 minutes in a 180C oven to make sure they’re entirely warmed through. You could even spritz them with a little melted butter and put them in the air fryer.

I love that it’s such a basic and versatile idea. The grim Edwardian, institutional roots of the thing are still there, but when I pick up a piece of “hot-smoked organic Canadian Coho salmon” in the supermarket — packed in a plastic pod and laden with signifiers of luxury and virtue — I’m still indulging in the same pleasant consumer delusions as my nan picking up “a treat” at the grocers.

The American crab cake

To make four

In the US, there’s an equally deep-rooted democratic tradition of stretching cooked fish into a glorious meal, though over there they prefer crabmeat. Maryland is usually credited with having the best crab cakes, though there are people up and down both coasts who will fight you in defence of their local variant. But the US crab cake is a very different beast and avoids the stodginess that’s the downfall of our fishcake.

A good crab cake is bound with as few cracker crumbs and as little mayonnaise as will hold it together. It’s a fiendishly brilliant strategy. There’s just enough egg in mayo to cohere, and the cooked cracker crumbs absorb juices without getting pasty. The centre will hold.

-

200g white crabmeat. Fresh is great, tinned is acceptable, the “pods” of it available in supermarkets are surprisingly excellent.

-

50g crushed saltine crackers (or panko will do brilliantly)

-

Old Bay seasoning, for authenticity. Possibly Worcestershire sauce or a smear of mustard if you fancy.

-

As little mayonnaise as possible to bind it

-

Clarified butter or ghee

Combine the crabmeat and crackers in a bowl. Season, then add in mayo, a little at a time and stir. Take it slowly. You need a mix that will hold together on a spoon but nowhere near the Polyfilla consistency of tuna salad. Taste and season again.

The use of clarified butters is so you can get your skillet really hot without blackening the butter. The intention is that, when you drop in a dollop of your mix, the underside crisps very fast. Push down the top of the mix to create a rough disc but do it lightly and then, the very second the bottom is crisp enough to hold things together, flip and quickly sear the top.

Done right, the American crab cake is a lovesome thing which, though it pains me to admit it, has quite the technological edge over our own version.

The ultimate fishcake

To make four

This is what brought me to Grimsby. Smoked haddock is famously the principal ingredient in an omelette Arnold Bennett and it would make plenty of sense to bind our fishcake with rich hollandaise and flavour with lashings of cheese, but we’ve learnt a lot since 1929 when Chef Virlogeux created it at The Savoy. We need something less heavy, less stodgy . . . and now we know the way to go.

The ingredients for this recipe are precisely the same as the American crab cake, but we substitute excellent smoked haddock for the crab and you can swap saltines out for water biscuits or even cream crackers.

Use a Finnan haddock if you can get one, or decent-sized piece of undyed smoked haddock if you can’t. Wrap it in a foil envelope and put it into a 180C oven for 15 minutes.

Let it sit for a while in its own steam, then open the parcel and you should be able to lift just-cooked flesh off the skin and bones. Chill this quickly and store it in the fridge. With luck you’ll have enough to make a couple of fishcakes and have enough left for an omelette the next day.

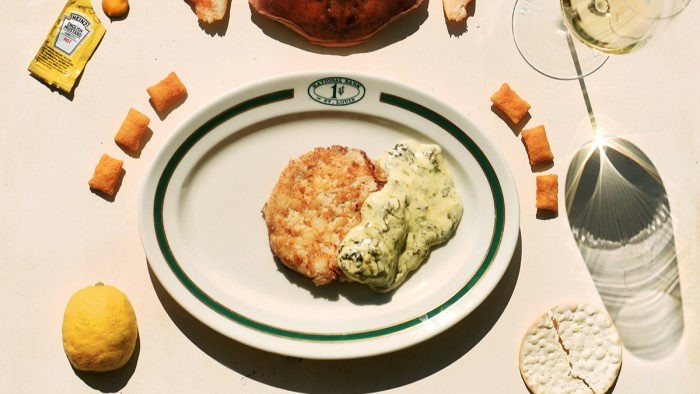

Wilt 500g of sorrel in a hot pan with a lid. It will reduce massively to an amusing green sludge. Drain, squeeze dry and put it to one side. Melt 15g of butter and stir 15g of flour into the pan. Stir this roux until you smell cooking biscuits then slowly add cold milk, stirring and heating gently, until you achieve a consistency that will stick to a fishcake without running off. Nobody will tell you off if part of that milk is replaced with double cream. Stir in the wilted sorrel. With a little seasoning, this will be your sauce.

Build your fishcake exactly the same way as the American crab cake, and cook in clarified butter. You can, if you wish, smish down the fishcake a little more. We want this one to hold together, because you could, of course, serve it, noble and handsome, on fine china; but you could also stick it in a gorgeous, soft bap, which somehow feels more, I don’t know . . . British.

Find out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend Magazine on X and FT Weekend on Instagram

Read the full article here