Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

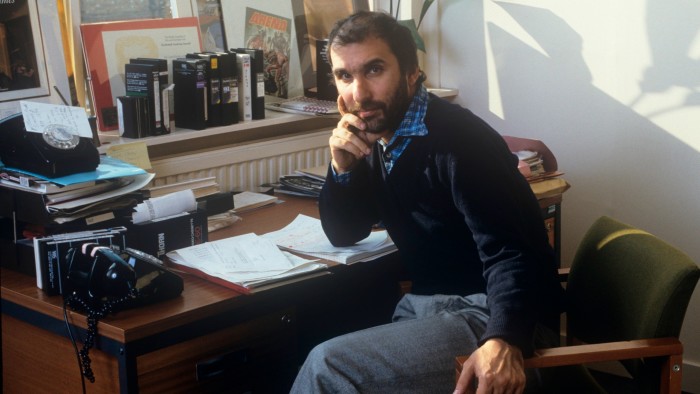

Accolades have poured in since the sad death last weekend of Alan Yentob, the former television producer, executive and interviewer, one of the most significant forces in British cultural broadcasting of the past 50 years. Noticeably it is the artists and writers themselves, whom he profiled on flagship series Omnibus, Arena and Imagine, who have paid eloquent tributes to his vision, boldness, boundless enthusiasm and genuine love for the arts. Over the decades he made powerful in-depth programmes on literature, visual arts, music, theatre, film and much else, and from Tracey Emin to Ai Weiwei, Dawn French to the Pet Shop Boys, Yentob’s passion and dedication have brought touching plaudits.

So what was it about this exceptional talent that made for such fine cultural broadcasting? Apart from simply having the power to do it, of course. After joining the BBC as a trainee in 1968, he rose quickly through the ranks and in a life-long career at the corporation held almost every key job: head of music and arts, then controller of BBC Two (one of the youngest ever), then supremo at BBC One, finally the BBC’s overall creative director. His career coincided with a time of radical growth and change in British cultural life and television was storming ahead, often with Yentob at the helm: he commissioned or greenlit classics from Absolutely Fabulous to Dragons’ Den, The Office to Wallace and Gromit and many more, and later launched children’s channels CBBC and CBeebies.

In Yentob’s own programme-making, the turning point came much earlier, with a revealing 1975 rockumentary on David Bowie called “Cracked Actor”, for the Omnibus series. The pop star was seen fragile, exhausted, cocaine-addicted; conversations took place, Yentob remembered, “in hotel rooms in the early hours of the morning, or in snatched conversations in the back of limousines”.

A new form was taking shape. Not only was it the first time the BBC had devoted a whole programme to a pop star, it heralded something else. As director Beeban Kidron says, “Alan had a gift (and a determination) to make arts accessible, whether it was ‘high’ art for which he found a broad audience, or revealing the relevance and import of so-called low art.”

This genre-crossing was in the zeitgeist of the time, and when Yentob took over the Arena series he made waves by devoting a 1982 episode to the Ford Cortina car as a cultural icon. Once Imagine was launched, in 2003, programmes similarly ranged from Philip Roth to Jay-Z, Velázquez to Beyoncé, Van Gogh to Freddie Mercury. There were artistic super-celebs galore — the Rolling Stones, Roald Dahl, David Hockney, Marlon Brando — but also a programme on Scrabble. Another on the history of surrealism, or on tall buildings.

Yentob’s background must have fed this inclusive, international take on the arts. He was born in Stepney, east London, in 1947, one of a pair of twin boys, sons of Jewish immigrants from Iraq in the textile business. The family moved to Manchester, then back to London in grander circumstances; Yentob studied at the Sorbonne in Paris and the University of Grenoble, then took a law degree at the university of Leeds. He was no stellar student, as university drama had become more absorbing: people skills were Yentob’s strongest suit. His must have been one of the world’s great address books, and less kind commentators charged him with Olympic-level name-dropping.

But the talent for people was clearly part of his secret, as ceramicist Edmund de Waal remembers: “He was the best interlocutor, running through registers of response and enquiry, funny and tough and generous.” For sculptor Antony Gormley, Yentob was “instantly intimate, instantly on your side, instantly interested in everything that you were doing, had done and were about to do. He had an energy and an eagerness that was never trespassing but always wanting to understand and join you in the adventure.”

Such sympathy with his subjects sometimes led to accusations of hagiography, and certainly there’s rarely a breath of criticism in his work: rather, his method was to immerse himself as deeply into their world as possible, travelling with interviewees, hanging out with them at home and at work, sometimes over weeks or months.

Making films that way is, of course, very expensive. Over the past decade, budgets for cultural programming have been radically cut. The main channels make fewer and fewer programmes, preferring increasingly to buy in ready-made content from independent producers. There is competition, too: the BBC’s cultural output was quickly rivalled by ITV and Channel Four and then by Sky Arts, and streamers such as Netflix and Amazon have their own strands of cultural documentary and arts coverage. Podcasts are powerful; even museums make their own arts videos.

All these alternatives would suggest a richer cultural landscape, but the truth is that the UK’s broadcasting overall has actually become much the poorer: fewer original programmes, more superficiality, much less risk-taking. Without Alan Yentob, many feel, an era comes to an end. Gormley again: “Who will support, encourage and extend the creatives of today in the same conspiratorial, insightful and impassioned way as only Alan could do? His spirit will continue to inspire and be a benchmark for excellence in public broadcasting.”

Read the full article here