Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Virginia Woolf called the early years of the 20th century “the age of Augustus John”. The British painter, draughtsman and etcher was wildly successful in his lifetime, but also notorious. Emulating the Roma life he revered, he once went with wife, mistress and several bemused children in a caravan to Cambridge. When Ottoline Morrell, yet another of his inamoratas, turned up, expecting a romantic meal under the stars, she found only squalor and a crust of bread. None of this was conducive, ultimately, to Augustus’s art.

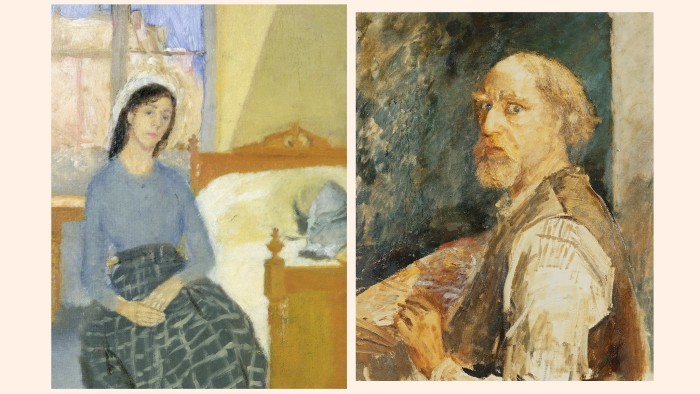

Meanwhile his sister Gwen was working in obscurity in Paris. In many ways theirs is the story of the tortoise and the hare. Quietly, Gwen became a great artist. Her dissolute brother, penitent after each new escapade, was not without an inkling of this. “In 50 years’ time I will be remembered as the brother of Gwen John,” he predicted, glumly.

In fact, both their reputations endure, though hers outstrips his. Artists, Siblings, Visionaries, Judith Mackrell’s splendid double biography, does full justice to each of these prodigious talents, who were at once rivalrous, affectionate yet conflicted with each other. They grew up in Wales, then both attended the Slade School of Fine Art in London in the 1890s, the one British art school that would take women at that time.

Inevitably, less was expected of the female students, but it was here that Gwen found her crucial community of gifted women artist friends, a circle that included Edna Clarke Hall and Ursula Tyrwhitt. Yet Gwen’s life was harder than her brother’s. Augustus quickly found commissions and patrons, but she had to model for money, living in poverty until rescued by the American art collector John Quinn.

In 1904 she settled in Paris for life, and in the same year met the sculptor Auguste Rodin. “I think if we are to do beautiful pictures, we ought to be free from family conventions and ties,” Gwen had written earlier, with instinctive radicalism. Rodin blew all this away. “I was born to love,” she writes, even offering to give up her art for his sake. She was ready to sweep his floor and button his boots; would loiter in the street by his house just to glimpse him. It was all too much for Rodin, who backed off.

Mackrell conjures the changing world they inhabited, including the great war, and the influences they absorbed — Cézanne being a mighty presence for both. She handles the two narratives deftly, and portrays the siblings with fine, acute perceptiveness. Augustus’s depression fed his need for drink and women. But with women came, eventually, nine children to support. This pushed him to do lucrative society portraits — which in turn ate away at his ideals and talents. Half destroyed by his own desires — by the very freedom his sex enjoyed — he nevertheless lasted until 1961, outliving his sister by 22 years.

If Augustus emerges as impossible but warm-hearted, Gwen is odder. In her affairs with both men and women she was liable to become so obsessively ardent and demanding she alienated the other. Excruciatingly shy, she had her artistic egotism too — her friend Dorelia sensed something “hard and queer” at the core of her.

“To me the writing of a letter is a very important event,” wrote Gwen. “I try to say what I mean exactly. It is the only chance I have, for in talking, shyness and timidity distort the meaning of my words in people’s ears.” These words go to the heart of her — the urge to communicate, alongside the fear (“shyness and timidity”). Add to the mix those roiling feelings that burst out when she fell in love, and the cocktail is a complex one. She was not easy in the world. It is surely this tension that contributes a hard-won, precious quality to those chalk-infused effulgent interiors, with their ecstatic colours; those startlingly resolved, yet probing portraits.

In 1913 she converted to Catholicism. “God your lover is waiting for you,” she wrote in her notebook — the bulwark against treacherous humans. Late in life, ill, she told herself there must be no more: “1 sitting before people, listening to them in an idiotic way 2 undergoing their influence — being what they expect — demand 3 by fear flattering them 4 valuing too much their signs of friendship 5 Thinking too often of people.”

More than God, art was the constant. “I feel more than ever on the point of knowing how to express things, in painting,” she wrote, 10 years before her death. Modestly, cautiously, she pursued her vision to the last.

Artists, Siblings, Visionaries: The Lives and Loves of Gwen and Augustus John by Judith Mackrell Picador £30, 448 pages

Kathy O’Shaughnessy’s novel ‘In Love with George Eliot’ is published by Scribe

Join our online book group on Facebook at FT Books Café and follow FT Weekend on Instagram, Bluesky and X

Read the full article here