Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

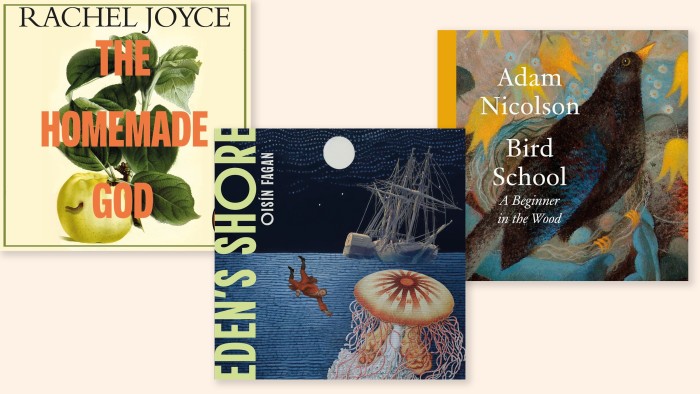

A long and rain-streaked Easter journey was enlivened by the sound of Rachel Joyce, author of The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry, reading her new novel. The Homemade God (Penguin Audio, 12 hrs 43 mins) takes us to a tiny island on Lake Orta in northern Italy, where four siblings gather in the wake of their artist father’s sudden death. The unusual cause — an apparently accidental drowning — is further complicated by his recent and hasty marriage to the elusive Bella-Mae and the absence of both a will and his much talked-of work in progress. As the set-up suggests, there is an element of unfolding whodunnit to proceedings, but it is largely secondary to the story’s real emotional meat: the agonising struggle to find a place for grief in an already fragile network of intimate relationships.

The key is tone, and Joyce, who was an actor before she turned exclusively to writing, modulates hers with immense delicacy. It’s impossible not to feel the comedy inherent in the siblings’ well-worn to and fro, nor the sorrow when their bonds begin to break down: hyper-capable but boozy Netta, who stood in as a mother when theirs died prematurely; fretful Susan, locked into a marriage with a father figure as kind as her real dad is careless; unworldly younger children Gustav and Iris, each given to flights both fanciful and actual. She captures their closeness and estrangement with impressive fleetness and sympathy, just as she gives voice to the impossible patriarch, Vic, and Bella-Mae herself, who when she finally arrives on the scene is as changeable and capricious as the lakeside mist.

I was entirely drawn into the sad, meditative world of The Homemade God, even as I thanked the fates that I was not marooned in an overheated and isolated villa with its inhabitants.

You could hardly get a more different listening experience than Oisín Fagan’s Eden’s Shore (John Murray, 11 hrs 38 mins), read by Tom Alexander. If Joyce’s Kemp family are hamstrung by an inability to fly clear of the nest, Fagan’s Angel Kelly is at the other end of the scale: a reckless adventurer who quits 18th-century Dublin with barely a clue of where he’s going or what he’ll find when he gets there.

It’s a tremendous romp of a tale, which begins with Kelly boarding a ship filled with mutinous seafarers and slaves desperate to regain their freedom and eventually lands on South American shores beset by colonialism and conflict. Throughout, Alexander’s capacious performance is made to encompass the visceral, physical experiences of the journey — disease, sex, seasickness, violence — and its more cerebral aspects, in which the politics, philosophy and idealistic utopianism of the day find expression. Here, too, are the multiple languages, cadences and rhythms of a shifting multicultural population, each of its denizens desperate to navigate their way to a place of greater safety.

Recently shortlisted for this year’s Women’s Prize for Fiction, Nussaibah Younis’s Fundamentally (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 9 hrs, 41 mins) is a wildly witty debut novel, delivered by Sarah Slimani with exactly the right combination of irreverence, brittleness and humour. “It’s not like I was expecting Stalingrad”, thinks academic Nadia on her arrival in Iraq, “but Baghdad took the piss.” Why are there fairy lights on palm trees and neatly parked BMWs? “Hadn’t I donated to help the Iraqi women giving birth in cow sheds lit by the flame of a single candle?”

Nadia is swiftly confronted by the gap between theory — she has written extensively on “IS brides”, to her considerable professional advantage — and practice, especially when she forms a close friendship with Sara, a prime example of the phenomenon now awaiting the next step in a refugee camp. And perhaps the biggest barrier to anyone moving forward, beyond ideology, faith and radicalism, is presented by the entrenched and bureaucratic aid bodies there to alleviate the situation.

Nadia’s voice is a quicksilver delight: she moves from fired-up determination to be part of the solution, to disillusion and disappointment, to a perilous self-doubt. And in her combative, often mistrustful but insistently burgeoning friendship with Sara comes the novel’s captivated underside — two determined if slightly confused protagonists finding their way through young womanhood in unforgiving circumstances.

And now for something entirely different: Adam Nicolson’s Bird School (William Collins, 11 hrs 53 mins), in which the nature writer confronts a gap in his knowledge — he has never, he tells us at the book’s outset, paid much attention at all to birds — and goes about filling it. Read calmly and steadily by Leighton Pugh, this is a book to listen to as you go on a walk or look through your window; even urban dwellers without easy access to the countryside will learn much about the creatures flitting about in front of them. And it’s also, as so much contemporary writing about our environment inevitably is, a paean to what we are in danger of losing.

Join our online book group on Facebook at FT Books Café and follow FT Weekend on Instagram and X

Read the full article here