European asset managers are following their US counterparts in “pulling back” on a public show of climate action while still quietly assessing risks and new regulations, fund managers, lawyers and consultants told the FT.

When a group of investors met this month to discuss putting pressure on Shell at an upcoming annual meeting over its oil and gas growth strategy, there was a notable absence of the asset managers who had joined in filing climate resolutions in the past, those present said.

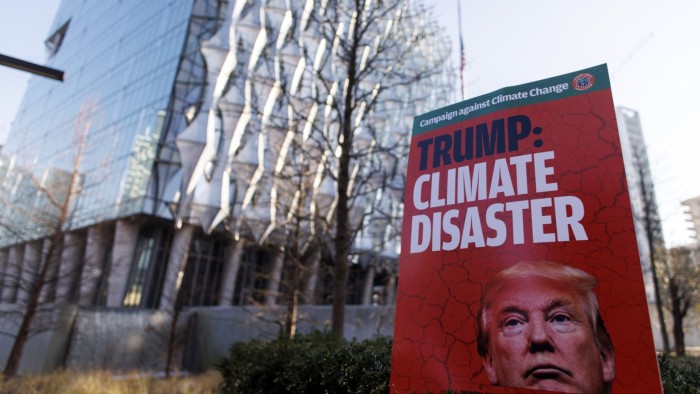

Across Europe, leading managers were taking cautious approach and “tiptoeing” around socially responsible investing matters, following Donald Trump’s election as president and right-wing campaigns against so-called environmental, social and governance investing over the past year.

Natasha Landell-Mills, head of stewardship at Sarasin & Partners, a UK asset manager, said: “The chilling effect from the increasing politicisation of climate change in the US is certainly spreading to Europe and beyond.

“The danger is that we end up harming ourselves and future generations by pulling back.”

Financial institutions in Europe have mostly gone further and faster than their peers across the Atlantic on climate pledges and transparency on socially responsible investing.

This means they are now grappling with the difficulty of putting into practice commitments to cut greenhouse gas emissions across their balance sheets, funds or dealbooks, as the wider economy is slower to wean itself off fossil fuels than was expected when the targets were set several years ago.

In 2025, some EU financial institutions must meet onerous climate and biodiversity reporting requirements, which can require them to disclose progress made against voluntary targets.

This ups the ante on their decarbonisation promises, made based on methodologies for carbon financial accounting that are still relatively new.

Commitments to “align” investments with the Paris agreement target to limit global warming to no more than 1.5C above pre-industrial levels now seem unrealistic to some. “It’s a bit demotivating to be set an incredibly tough goal with ineffective ways of getting there” said one Paris-based financier, in reference to the EU’s perceived preference for green regulation over subsidies that could support the energy transition.

Many of the net zero ambitions were set at a time when the industry was “not scrutinised like we are now and the balance of risk wasn’t what it is now”, a senior asset management executive said. Internal lawyers had become much more likely to push back against sustainability targets and pledges that executives might be challenged about, they added.

Several European asset managers said they had received letters from Republican states threatening legal challenges to their focus on ESG issues including any potential exclusion of fossil fuel investments.

The industry’s Net Zero Asset Management voluntary group on climate action this month suspended its public activities after litigation against US counterparts such as BlackRock forced their withdrawal from the coalition.

ExxonMobil’s decision to sue Arjuna Capital, a US investment adviser, and Follow This, an activist group, last year over a climate-related resolution they had filed at the oil company’s annual meeting was a watershed moment, sparking fear across the sector — even in Europe.

European investors were now not only reluctant to speak out about US companies but were also “being more cautious about European companies”, the senior executive added.

They are also less willing to back climate resolutions at annual meetings. Support for such proposals globally among Europe’s biggest asset managers fell from 84 per cent in 2022 to 69 per cent in 2024, according to data from FTI, the consultancy.

Yet several top European asset managers say a focus on climate will continue to be a priority, as they try to balance the conflicting climate backlash in the US with institutional client demand for risk control and tighter regulations in Europe.

Those asset managers were “not adjusting their investment strategy to a four-year political cycle”, one chief investment officer of a leading European fund manager said, but instead were taking steps to “protect themselves from open criticism” by not putting a spotlight on their actions.

Behind the scenes, some leading asset managers continue to push for action to reduce climate risk at the companies they invest in, they added.

Stephen Beer, head of responsible investment strategic relationships and integration strategy at Legal and General Investment Management, the UK’s largest asset manager, said interactions with companies over climate change were now “harder edged”.

“We are talking about business strategies, progress towards transition, decisions that companies have to make” he said. “And that is exactly where we want to be in conversations with companies, because we want them to be profitable and sustainable.”

At the same time, European pension funds were doubling down on their climate efforts, said Jon Johnson, chief executive of PKA, the big Danish pension fund, leaving asset managers who retreated at risk of losing clients.

“We as asset owners will have to take the lead right now [on driving action on climate from the finance sector] . . . If we keep on pushing for the green transformation, I am sure from a business perspective, [asset managers] will want to keep that growth.”

He added: “A lot of asset managers, both in the US and Europe, are tiptoeing around how to do this right.”

Such calls from asset owners — and more supportive politics in Europe — meant the continent’s asset management industry would continue to focus on climate change, said Sonja Laud, chief investment officer at LGIM.

“Climate is a financially material aspect in understanding a company’s future success and we will continue to include it in our investment process. To identify the right investment opportunities for our clients, climate risk has to be an integral part of the analysis,” she added.

Landell-Mills at Sarasin said the industry could not ignore climate change, despite the political pressures and regulatory burden.

“Ultimately, the fundamentals haven’t changed. Climate change is still happening. Ignoring the risks doesn’t make them go away. But it delays action to tackle them,” she said. “Climate change is going to have massive economic impact, a massive geopolitical impact — and that will affect returns.”

Read the full article here