By Harry James Relf

Have you ever found yourself caught in the endless churn of city living? Moving from one astronomically expensive flat share to the next, unable to settle thanks to stagnant wages and insecure housing? If you have, then this ode to Good Will Hunting might hit home, because the film is not just the story of a genius hiding in plain sight, it’s the reality of renting for my generation — Gen Z.

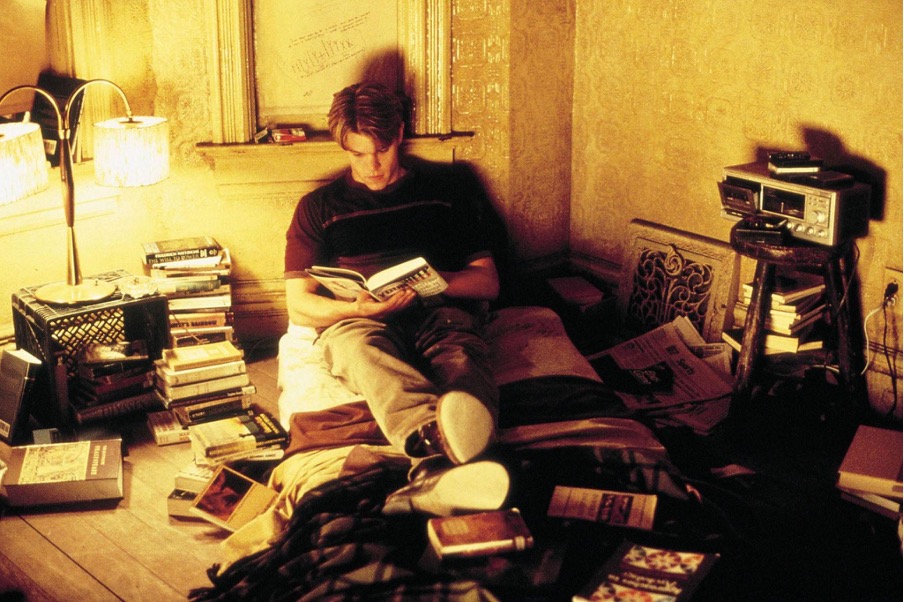

I first watched Gus Van Sant’s 1997 film, starring Matt Damon as Will Hunting (pictured above) and Ben Affleck as Chuckie Sullivan, when I was 16, in my family home after finishing my GCSEs. What has stayed with me isn’t just the drive of the film — Will’s inability to embrace his obvious potential and live a different life — it’s the apartment he calls home.

Years later, when my “home” was a friend’s couch, I rewatched the film and realised that though some people would see Will’s living conditions as a metaphor for the rootlessness of youth, for me it was reality.

His south Boston apartment is bare: a mattress on the floor, chalk dust on a window that never quite opens, a few possessions scattered around the floor. The glow of a lampshade throws a halo of warmth into a room otherwise stripped of comfort. To a transient renter like me, these details are all too familiar.

Of course the film isn’t about housing insecurity: Will’s transience is more emotional than financial. Yet the refusal to settle in a space, decorate it or invest in it, is an instinct I recognise in myself. Like me, Will isn’t seeking comfort, he’s seeking control. And in a brutal rental market, any semblance of control is a rare luxury.

Will’s complex relationship with Skylar, played by Minnie Driver, contrasts his working-class roots with the privileged world she inhabits. A scene in a Harvard bar serves as a microcosm of this elitism, highlighting the social and intellectual divide between Will and the academic world — or between those who don’t have to worry about securing their deposit and those who do.

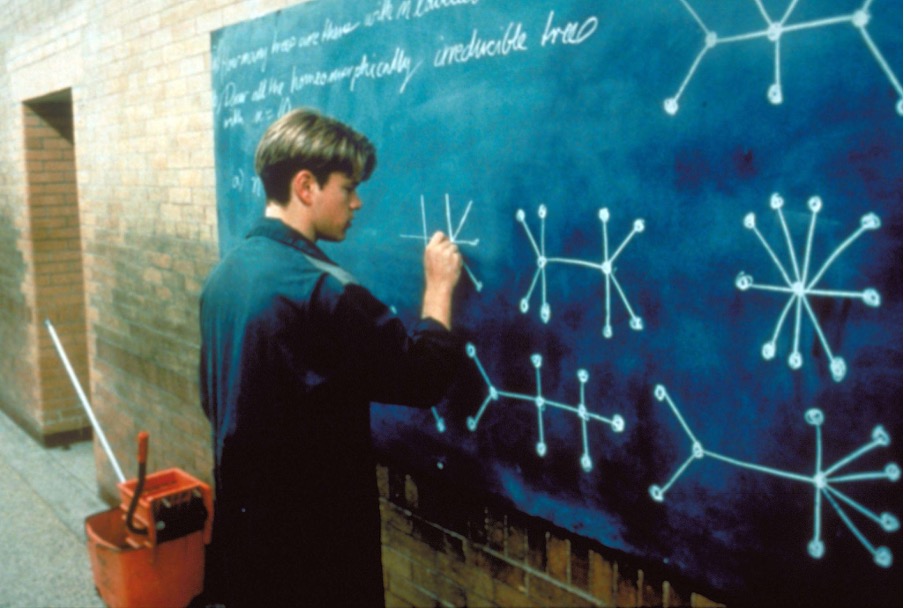

The film cuts between Will’s home life, his love life with Skylar and a recurring shot of him sinking into the red plastic seats of a Massachusetts subway car. Every day he travels to and from his unadorned apartment and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), where he works as a janitor. While my own routine isn’t as monotonous as Will’s (nor do I spend hours cleaning university corridors, thankfully), there’s something in the scene I recognise — the sense of being capable of more yet trapped by circumstance.

When Will finally gets Skylar’s number, he spots an arrogant Harvard student he outsmarted earlier in the film in a café. Delighting in another small victory, Will slams the phone number against the café window. “Do you like apples?” he asks. “Well, I got her number. How do you like them apples?” In my version of the scene, it’s me waving a signed tenancy agreement. “I got the flat. How do you like them apples?”

During the famous park-bench scene, Robin Williams’s character, therapist Sean Maguire, forces Will to confront not only his fear of love, or of failure, but his reluctance to embrace the feeling that he belongs anywhere.

In a 4-minute-47-second monologue, Sean dismantles Will’s defences. Playing devil’s advocate, he exposes the limits of intellect and the power of lived experience. His words cut through the same armour I wear — the one my generation has built as we try to appear put-together while feeling emotionally stretched and endlessly renting in cities that never let us settle. The scene subtly peels away the claustrophobia of Will’s apartment, replacing it with an outdoor, open air perspective, helped by the obvious connection between the two characters.

At the end of the film, Will gets into his car — a gift from friends — and heads west, “Miss Misery” by the late Elliott Smith cueing the end credits, and it’s clear his journey isn’t just about finding Skylar. It’s about finally daring to build a life beyond all he’s ever known.

I think that’s what I’ve been searching for too, not a home in the physical sense, but the courage to stop treating every space, and every part of myself, like it’s temporary. I’ve had my time in borrowed rooms, so maybe it’s time to take the advice of Will’s therapist and make my move, chief.

Photography: Alamy; Shutterstock

Read the full article here