Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

As the nights close in and the fairy lights go up, what the season calls for is unwise quantities of sugarplums, eggnog and hot toddies — and a haunting, wintry novel. For many readers, curling up with cozy crime, ghost stories or novels that conjure up the spirit of brooding winter is a key festive tradition.

Contemporary writers have imagined and reimagined Dark Christmas with considerable flair, especially horror and crime writers. Joe Hill’s NOS4A2 (2013, pronounced “Nosferatu”) features a terrifying theme park called Christmasland, whose owner kidnaps children, leaving them trapped among snowmen who never melt and all the other creepy trimmings of a forever Christmas.

In the past century, crime writers from Agatha Christie to PD James have tried their hand at the Christmas short story or novella. In Hercule Poirot’s Christmas (1938), a slew of resentful relatives gather at Gorston Hall, and an unpleasant multi-millionaire gets it in the neck.

PD James’s Christmas stories, written for magazines, were collected and published as The Mistletoe Murder and Other Stories in 2016, two years after her death. She jettisoned the usual Cosy Christmas agreement to leave murder victims in a tasteful but discreet welter of blood; her corpse, another dislikeable relative, has a crushed skull. James was brilliant at recreating the atmosphere of an old country house during the second world war, with blackout curtains at the windows, “Jeepers Creepers” and “Tiger Rag” on the gramophone, and festive goose with Christmas pudding as a pre-murder repast. “Good people were dying all over the world and the fact that one unlikeable one had been killed seemed somehow less important,” her narrator observes.

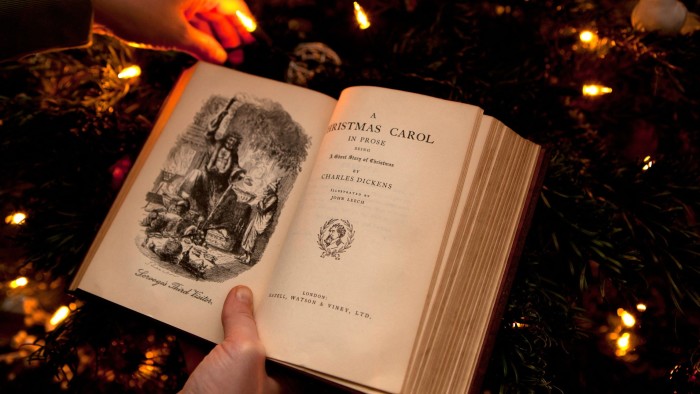

Perhaps stories of winter and Christmas were always meant to be spooky. Though many will only remember the joyous, unabashedly sentimental ending to A Christmas Carol, Charles Dickens’s 1843 classic was “A Ghost Story of Christmas”, as advertised in the subtitle. “May it haunt their houses pleasantly,” Dickens wished his readers.

He begins in “cold, bleak, biting weather”, the fog “pouring in at every chink and keyhole”, with Ebenezer Scrooge calling down curses on the fools who celebrate: “every idiot who goes about with ‘Merry Christmas’ on his lips, should be boiled with his own pudding, and buried with a stake of holly through his heart”. So much of A Christmas Carol is about terrible mistakes and life’s wrong turns — even though it ends with great feasts, jollity and literature’s most improbable change of heart (assisted by three spectres).

Of the modern era, one of my favourites is Alaskan writer Eowyn Ivey’s haunting fable, The Snow Child (2012), set in 1920s Alaska. Ivey refashions a Russian folk tale, following an older couple, Jack and Mabel, into the winter of their marriage, where they endure a time of struggle until one day they craft a little girl out of the snow. Soon after, she seems to come to life, and Ivey gives us a superb if bittersweet modern fable.

It is hard to write the seasons afresh, to make the reader feel winter seeping through the pages of a book for the first time. But Andrew Miller does that, in his atmospheric The Land in Winter, set during the Big Freeze of England in 1962-63, capturing the sense of a blizzard closing in: “The dusk came swiftly. In the garden, the snow lay in subtle undulations, each with its deepening blue shadow. The cold descended and the land tightened.” I was swiftly drawn into the lives, marriages and betrayals of two couples at a time just before a spring of intense change, caught between an old, rigid world and a new, not-there-yet land of promise.

In his novel, which was shortlisted for the 2025 Booker Prize, Miller makes you feel the snow piling up above your head, the ground frozen iron-hard. Winter and Christmas novels should either cut through the marshmallow-and-candy sugariness of an over-commercialised season or, like Miller and James Joyce before him, they bring you back into the heart of winter itself.

Joyce wrote arguably the best description of a winter feast ever in “The Dead” (1914), in which a family table groans with a fat brown goose, a round of spiced beef, jelly, blancmange, Smyrna figs and a host of other delights. But he also wrote one of the greatest final paragraphs in literature, after reminding us of an Irish winter, the air fragrant with snow. Following heartbreak and losses, the snow would still be left: “the flakes, silver and dark, falling obliquely against the lamplight”. Cold lines, written by a warm heart; that is what I want from Christmas fiction.

Join our online book group on Facebook at FT Books Café and follow FT Weekend on Instagram, Bluesky and X

Read the full article here