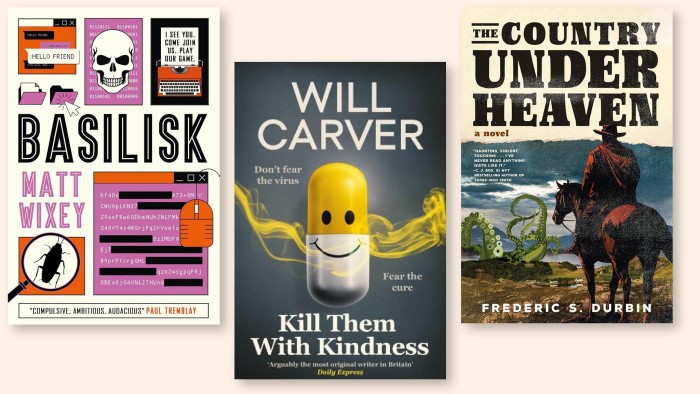

If you’ve ever felt that the internet is a strange, hostile domain filled with untold hazards for the unwary, then Basilisk (Titan £9.99) is the book for you. Or maybe, unless you want your worst fears confirmed, not.

In Matt Wixey’s sophisticated, byzantine debut we meet Alex Webster who, along with her fellow ethical hacker Jay, becomes fascinated with an online game, a series of baffling puzzles set by an entity known as The Helmsman. The pair soon come to understand that anyone who succeeds in solving these conundrums goes mad and ends up committing suicide or murder.

The Helmsman has devised a “cognitive weapon”, a deadly mind virus buried in programming code. To make matters worse, Alex and Jay are also being menaced by nightmarishly grinning, impeccably polite strangers, pawns of an organisation whose name is redacted throughout the book, replaced with a solid black bar.

This last is just one of many textual tricks played by Wixey, whose background is in cyber security. Basilisk teems with marginalia, footnotes, hyperlinks, short plays, scholarly articles, embedded images, typographical shenanigans, even a cryptic crossword and a QR code.

The nearest equivalent one can think of is Mark Z Danielewski’s claustrophobic horror opus House of Leaves (2000). There’s the same intricate metafictional layering here and the same hefty word count, not to mention the same almost palpable sense of unease, as though something unfathomably sinister lurks within the very wood pulp of the pages. Few authors can or would lavish their novel with this much peripheral material and depth of detail.

By contrast, Will Carver’s Kill Them With Kindness (Orenda £9.99) adopts a pared-down, neutral-toned reportage style, and is no less effective for that. It tells of a scheme to unleash a lethal coronavirus on the world, conducted by an elite cabal that stands to profit in various ways.

At the heart of the plot is UK Prime Minister Harris Jackson, an habitual liar and serial adulterer who affects a buffoonish swagger to hide his innate ruthlessness and cunning. He knows that the best way to control the electorate is by stoking fear and generating an increased reliance on government intervention.

Meanwhile, a Japanese scientist, Dr Ikeda, has cooked up a virus of his own that instils altruism and compassion in those it infects. Idealism clashes with political cynicism in a scathingly pointed satire that serves as a reminder of how the pandemic brought out the best in people but also, in some instances, the very worst.

The American West in the late 1800s seems downright uncomplicated by comparison, a place where just a horse, a six-gun and a solid sense of righteousness could carry a man far. That, at any rate, applies to Ovid Vesper, protagonist of The Country Under Heaven (Melville House £14.99) by Frederic S Durbin.

Ovid, survivor of the bloody, ferocious civil war battle at Antietam, has elected to spend his days travelling cross-country, helping out folks in need. Unfortunately for him, he’s dogged by prophetic visions that pivot around a formless, skulking figure he calls the Craither. He also finds himself battling cannibal cults and supernatural monsters, returning a pair of otherworldly green-hued children to their own realm, and fending off bandits who covet a hoard of strange gold he’s got his hands on.

The novel unfurls episodically and is narrated in the kind of lilting, old-timey vernacular that often rises to the level of demotic poetry. Like last year’s notable entry in the “weird Western” genre, Red Rabbit by Alex Grecian, The Country Under Heaven is best considered as a spooky tall tale told around a campfire on a dusty sagebrush plain while unseen predators prowl and howl in the darkness just beyond the glow of the flames.

Land of Hope (Indigo Press £12.99) by Cate Baum is also couched in dialect, in this instance broad Yorkshire. It’s the story of Hope Gleason, also known as Glory, who has been living wild on the moors since her husband Bill, a broodingly charismatic man who turned out to be a rapist and murderer, was sent to jail.

A mysterious sound, accompanied by inexplicable lights in the night sky and a snowfall of weird white seeds, brings widespread death, and Hope decides to go to where Bill is imprisoned and free him, believing he’s her only chance of surviving this national catastrophe. Joining Hope on her questionable quest are her dog Jip and an orphaned boy she has rescued, whose name we (and she) never learn.

This is tense, uncompromisingly brutal stuff, as gruelling and hellish as Cormac McCarthy’s The Road. Yet there are flashes of beauty amid the apocalyptic bleakness: the raw majesty of landscape, nature’s resilience in the face of humankind’s destructiveness, the possibility of love blooming in even the most barren of hearts, and a willingness to admit guilt, however belatedly.

James Lovegrove’s latest book, his 69th, is ‘Conan: Cult of the Obsidian Moon’

Join our online book group on Facebook at FT Books Café and follow FT Weekend on Instagram, Bluesky and X

Read the full article here