Ithell Colquhoun and Edward Burra — it’s an ambitious concept to yoke two relatively obscure artists whose only apparent connection is that they were British, born a year apart at the turn of the 20th century and glancingly associated with surrealism in the 1930s.

Tate Britain thinks otherwise, however, and has twinned them for a double-header. One ticket grants you entrance to both exhibitions, which unfold across adjacent spaces.

At first, the pairing feels baffling. Colquhoun’s abstract but half-recognisable forms, quivering with mystical energy; Burra’s antic take on the desperate gaiety and rising tensions of the interwar years.

And yet they gain in being considered together. Both saw in landscape splinters of divine splendour, both preferred watercolour, reinventing it for their own purposes. Both experienced a crisis of faith that emerged in their work as grief. Come looking for gentle harmonies, then, rather than anything more contrived.

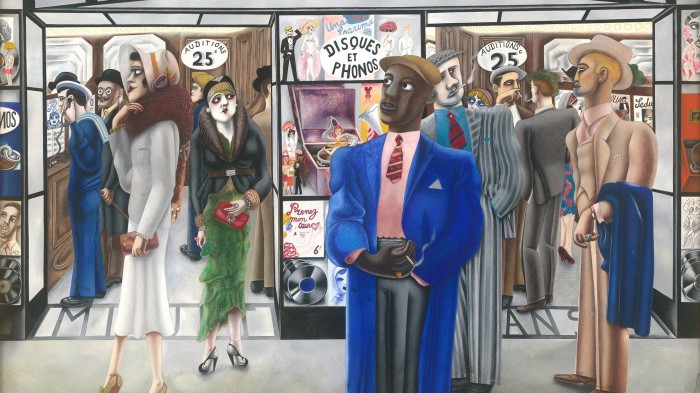

Which to start with? I chose the Colquhoun show, which comes fresh from a buzzy run at Tate St Ives, but spent far longer in and much preferred the one dedicated to Burra, whose reputation isn’t all it ought to be. His fate has been to be pigeonholed by his brilliantly arch paintings of jazz-age fleshpots in London, Paris and New York, and of these there are a satisfying number on display. But the artist — the person — who emerges here is a more complex figure than those few famous pictures suggest.

We meet him without preamble: on the brink of leaving the Royal College of Art, his style fully developed, and already in the precarious health that blighted his life and curtailed his mobility (but spurred his art-making no end: “The only time I don’t feel any pain is when I’m working,” he said).

The works set out in this first room establish Burra as a painter of modern life, and a virtuoso of close observation. You want to get up close and enjoy the T-bar and Oxford shoes, the pressed trouser creases, lamp haloes and floor tiles, the tired barman at the counter, the sweaty crush of faces, the desire and desolation.

Many were painted in France, which Burra visited a dozen times between 1925 and 1933 (when ailments allowed, he was an inveterate traveller), but he was as taken with New York, indulging his love of jazz at the Club Hot-Cha or the Savoy Ballroom in Harlem. This is stylishly conveyed in a display of his gramophone records, whose tinny wails trail affectingly through the galleries.

Every so often, these pictures feature faces with unseeing white eyes, perhaps in a trance from the music, though Burra’s work took a definite turn towards the surreal at this time: lots of beaked birdmen, skeletons and so on. Initially they were macabre spice, still striated with his edge of humour, but as the decade progressed and events in Europe took a grim turn, his paintings exuded only darkness. Paintings such as “Wake” (1940) and “Soldiers’ Backs” (1942) are not easy to look at, but nor were they meant to be. Confusion rages in their shadows and if people appear at all, they are turned away, stiffened into racked arrangements.

In parallel — from the 1930s to the 1950s — Burra escaped into a world of make-believe, creating sets and costumes for the Royal Opera and Sadler’s Wells. His designs for Carmen and Rio Grande are unequivocally inventive, but those for Miracle in the Gorbals, a modern morality play in which Christ returns to earth in Glasgow, outshine everything else.

Tate saves the best for last, with a first-rate selection of Burra’s landscape paintings. He made them from memory, after tours by car with his sister Anne to Cornwall and the Yorkshire Moors. His friend the dancer and designer Billy Chappell recalled that on these trips Burra never made “any sort of note: not even the faintest scribble” and, because of this, the paintings are distillates of atmosphere and tone, Burra’s emotion tugging you to strange, silent places.

“Dartmoor” (1974) is a symphony of aqueous greys and greens. “Valley and River, Northumberland” (1972) more muted, but no less affecting. Some concern environmental degradation — the earth flayed, the fields veined by pylons — and, here and there, a ghost or hooded figure flits through, but mostly the land is empty. Burra is at its centre, the quintessential lone romantic.

I have wondered since if I was primed to see such things because I came to Burra primed by Colquhoun. Her mystical, spiritually infused worldview is so strong. Right from the start, we’re in an unusual world, with the figurative works that won her prizes at the Slade, many biblical or mythological in theme. Their sculptural style and earthy colouring draw heavily on the Italian Quattrocento, but already she is slipping into something envisioned rather than observed.

Though Colquhoun belonged for a brief time to British surrealism, exhibiting jointly with Roland Penrose in 1939, it sends you down the wrong path to approach this exhibition thinking of her as the latest “lost” woman surrealist. She shared their preoccupation with the inner landscape and was influenced by their automatic processes (where the artist cedes creative control to chance) and concept of the double image (where an image can be visually perceived in two ways). But her private magical practice (channelling the spirit world, tarot, manipulating energy currents) caused a fissure, and she left within a year.

Better to see the series of architectural and geological fantasies she created around this time as proof of her brilliance as a colourist. “Scylla (méditerranée)” (1938) is the star, glowing with pristine washes in oceanic shades, its ruffles of seaweed and rocky promontories flipping, as the eye and mind adjust, to a view of the artist’s body in the bath.

Discovering the hidden corners of the mind and universe became an obsession for Colquhoun and, after moving to remote Cornwall in the 1940s, she gave it full rein. These are the strangest of her paintings: “Parsemage”, in which powdered charcoal or chalk is sprinkled on water and an impression taken using paper; “Decalcomania”, where two surfaces with paint between are squished together to create a mirror image, like the butterfly paintings children make at school. And her “magical workings” — illustrations interpreting medieval alchemy, the Jewish Kabbalah and something called the Divine Androgyne.

Whether you believe in all this is neither here nor there. It’s the integrity of Colquhoun’s artistic vision that matters and the way it is presented here feels baggy. There are too many experiments on show; too many weak pieces and different styles, so that the point becomes vague.

Colquhoun’s strength returns in the final room, which hums with spiritual intensity. “Untitled (Dance of the Nine Maidens)” (1940) is a stunning sequence of quiet watercolours inspired by a Cornish legend in which a group of women were turned to stone as punishment for dancing. There are several consequences of the show having been slimmed down and reimagined for London — the jettisoning of archive material that might have grounded Colquhoun’s practice, for instance — but the smaller number of works relating to Cornwall is the most unfortunate, because it was that salt-lashed, magic-steeped piece of earth which truly unlatched her heart.

To October 19, tate.org.uk

Read the full article here