Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

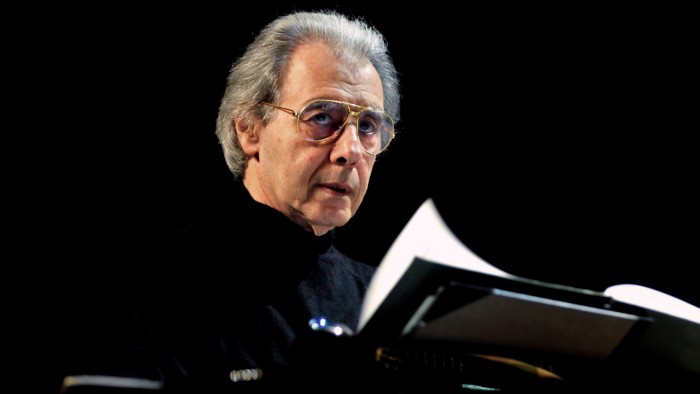

Write “something exciting” was Lalo Schifrin’s brief for a new US television series about spies that aired in 1966. The Argentine composer and musician, who has died in Los Angeles aged 93, turned this pithy command into one of the most distinctive theme tunes in screen history: the blaring horns and staccato tension of Mission: Impossible, a micro-masterpiece of stylishly pounding orchestral action.

When Schifrin met Tom Cruise, star of the spin-off Hollywood franchise, the actor hugged the composer and told Schifrin that his composition was the reason that Cruise had taken the role in the 1996 film. Schifrin was delighted. But this vibrant snatch of music, written in haste, was a tiny part of his prodigious output. He composed scores for films such as Cool Hand Luke, made jazz-classical fusion and bossa nova albums and formed a fruitful working relationship with Dizzy Gillespie. “I have had many teachers,” he said of the great jazz trumpeter, “but only one master.”

His training lay in classical music. Born in 1932, he grew up near the Teatro Colón opera house in Buenos Aires, where his father was first violinist in Argentina’s principal orchestra. When he turned five, the entire Buenos Aires Philharmonic played him “Happy Birthday”. He was taught piano by conductor-musician Daniel Barenboim’s father, a punishing taskmaster who would jab at erring hands with a sharp pencil.

Schifrin was a child when the nationalist junta that led to Juan Perón’s presidency seized power in 1943. He abhorred Peronism as totalitarian and sympathetic to Nazism. With a mixed Jewish-Catholic family background, he escaped to France in 1952, having won a scholarship to the Paris Conservatory. He won prizes in composition, orchestration and fugue. At night, he played piano in Left Bank jazz clubs, to the dismay of his distinguished teacher, the composer Olivier Messiaen.

His father, Luis Schifrin, shared Messiaen’s bemused disdain for the improvised nature of jazz. “If you can’t write it down or read it, it’s not music,” he used to scold his son. Schifrin rebelled against such strictures. The chauvinistic culture of Perón’s Argentina, where imported records were banned, was further fuel for his freethinking ethos. In his description, he was one of the “amphibians”, a musician equally at home in classical and jazz.

He first met Gillespie after returning to Buenos Aires. In 1960, he composed the “Gillespiana” suite for the trumpeter (“my mentor, my guru, my elder brother”). He moved to New York and joined Gillespie’s quintet as pianist in 1960. This was “one of the happiest times of my life in terms of music”, he recalled. But he left the ensemble in 1962 after tiring of touring.

The lure of soundtrack work drew him to Los Angeles. Mission: Impossible was his breakthrough. Having had his first effort rejected, he dashed out a piece of music in unusual 5/4 time. Typical of his wit and intelligence, the stabbing rhythm makes hidden use of the Morse code for the letters “M” and “I”.

He had further success with his jazzy theme for the detective show Mannix in 1967. That year also saw his first composing work for cinema with Cool Hand Luke, starring Paul Newman as a recalcitrant prisoner in a brutal prison in the Deep South. Schifrin elucidated the character’s inner resources with a rich blend of bluegrass, country, blues and jazz, ranging in mood from jaunty to pensive. Nominated for an Oscar, it was his favourite among his film scores.

Schifrin brought jazz’s sense of swing to the precisely timed synchronisation of film music. He added orchestral sophistication to pulp fare such as Clint Eastwood’s rogue-cop thriller Dirty Harry (1971) and Bruce Lee’s chopsocky classic Enter the Dragon (1973). When music was added to film, “a magic alchemy” took place for him. “It’s a new thing again, that has nothing to do with what you’ve seen or heard before. A totality of its own,” he said in 1967.

He lived in LA with his second wife Donna; she survives him, with his three children from his two marriages. He continued making albums alongside his film and television work, roaming around different cultures and genres — tango, Hawaiian music, Middle Eastern melodies, medieval church masses, opera — with scholarly curiosity but an artist’s sensibility. In 1993, he released Jazz Meets the Symphony, a fluent union of his two main musical poles.

For Schifrin, music was the true Esperanto, a universal language. In the immense mosaic of his work, his Mission: Impossible theme is merely a miniature fragment — but its dash and élan are the distillation of a brilliant musical mind.

Read the full article here