Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Mario Vargas Llosa, who has died aged 89, nearly became president of Peru in 1990. Standing on a liberal platform for the Democratic Front coalition, the novelist topped the first-round poll. Although routine in Europe and the US, Vargas Llosa’s blend of rule-of-law pluralism and suspicion of the overmighty state remains an exotic stance in Latin America. The camp of his populist rival Alberto Fujimori depicted him — as critics often did — as an out-of-touch elitist remote from his homeland’s indigenous masses. Fujimori (later sentenced to 25 years in jail) won the run-off but plunged the nation into a corrupt dictatorship.

If the Peruvian failed to become a writer-statesman like Václav Havel, he did later join the Spanish nobility as 1st Marquis of Vargas Llosa. And he had the bitter satisfaction of seeing Fujimori’s crimes echo a favourite plotline. Brilliantly, regularly, he wrote about the tyrants of right and left who seduced Latin America. The Feast of the Goat (2000) turns the Dominican Republic’s Trujillo regime into hypnotic and propulsive fiction as it dramatises “the enthronement, through propaganda and violence, of a monstrous lie”.

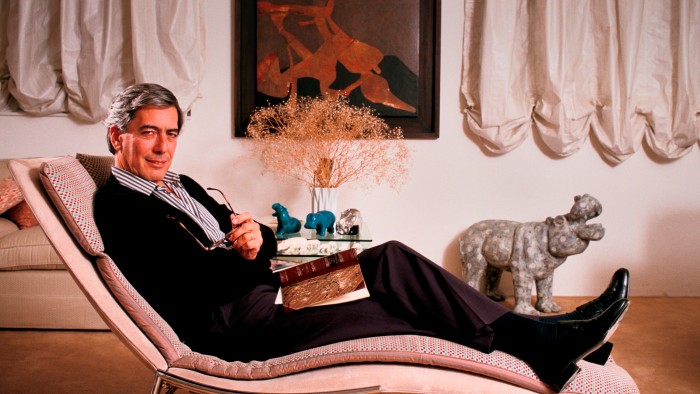

In 2010, the prolific, debonair but combative author of 20 novels and a shelf of essays and memoirs gained the one accolade that saluted his true gifts: the Nobel Prize in Literature. The Swedish Academy’s citation praised Vargas Llosa’s “cartography of structures of power and his trenchant images of . . . resistance, revolt, and defeat”.

That formula catches some abiding themes but misses his buoyant, high-spirited, ingenious pursuit of them. Among the giants of the Latin American “Boom” generation, Vargas Llosa was the endlessly versatile entertainer. He had written for TV soap operas; his witty semi-autobiographical romp Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter (1977) bears traces of the twisty, lurid telenovela. Yet this flexible shape-shifter could equally imagine a millenarian cult in Brazil (The War of the End of the World, 1981) or recreate the life of the Irish human rights campaigner turned rebel Roger Casement (The Dream of the Celt, 2010).

Vargas Llosa was born in Arequipa in 1936. The city’s Andes-shadowed setting and colonial legacy haunted his writing. His family combined a patrician, Spanish past with an unstable present. After divorce disrupted his childhood, a miserable spell at a Lima military school led to a sensational debut, The Time of the Hero (1963): first of many anatomies of power misused, and truth betrayed. He studied in Spain (where he later often lived), wrote in Paris and wed Julia Urquidi Illanes: his uncle’s sister-in-law. After their divorce, he married a cousin: Patricia Llosa, mother of his three children.

Back in Peru, the brothel setting of The Green House and the deep-state conspiracies of Conversation in the Cathedral (1969) united a scrutiny of institutional injustice with lavish and sensuous narration. For a period, Vargas Llosa and his (then) friend Gabriel García Márquez stood at the twin crests of an all-conquering wave. Politics drove them apart. “Gabo” kept faith with the revolutionary left, above all Castro’s Cuba, while Vargas Llosa’s “English” liberalism hardened. But it was a personal quarrel (related to his troubled marriage) that led the latter to floor García Márquez with a punch at a Mexican film screening in 1976.

At home, too, he got into fights. His free-speech activism made authoritarian enemies. After the Maoist guerrillas of the “Shining Path” launched their insurrection in 1980, Peru’s civil strife left deeper wounds. He led a disputed government investigation into a massacre of journalists, while the nation’s long agony of terror and repression bore fictional fruit in The Real Life of Alejandro Mayta (1984) and Death in the Andes (1993). Vargas Llosa now firmed up the liberal position — pro-human rights, but pro-business too — that would lead to his presidential run. Certainly, no other figurehead of the Latin American literary boom ever supped with Margaret Thatcher — whom he admired. (London, along with Paris and Madrid, became a home away from home.)

His campaign failure inaugurated a golden second term as a literary leader — from the spiky, salty memoir A Fish in the Water (1993) to the magisterial The Feast of the Goat and a pairing of pioneer feminist Flora Tristan with her painter grandson Paul Gauguin in The Way to Paradise (2003). Latin America’s way to paradise, he insisted, did not pass through charismatic populism. The Call of the Tribe (2018) rejects utopian plans in favour of the ironic pluralism of his liberal heroes: Adam Smith to Isaiah Berlin. Later novels such as The Discreet Hero (2013) display a topical bite and plot-driven zest hardly ever found in octogenarian Nobelists.

Sophisticated, dapper, cosmopolitan, Vargas Llosa could figure as a “neoliberal” ogre to leftists — a caricature belied by his work but reinforced by media provocations, such as backing the hard-right Jair Bolsonaro against Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva in Brazil’s 2022 elections. “Don Vargas Loser,” sneered one foe.

Latin America’s great authors have never had the luxury of working in a politics-free zone. That proximity has tended to do more harm than good. Such was the case for Vargas Llosa too. He will endure not as a thwarted power seeker but an eloquent, inventive scourge of its abusers, a virtuoso storyteller of private passions and public events alike — and a visionary interpreter of his continent’s dreams of a better life for all.

Join our online book group on Facebook at FT Books Café and follow FT Weekend on Instagram and X

Read the full article here