Martin Parr, who has died aged 73, was the most celebrated photographer of British life in the past half century, and the most controversial. A pioneer of supersaturated colour in documentary photography, he created lurid, sardonic, precisely detailed, entertaining images of working-class and middle-class everyday leisure with an anthropologist’s forensic eye, a stand-up comic’s deadpan humour, and the artistry of a formal master.

From his initial major series, The Last Resort (published 1986), depicting holidaymakers sunning themselves on the dilapidated promenade of New Brighton, near Liverpool — brightly coloured swimsuits, howling children, buckets of fast food and litter everywhere — Parr changed the terms of photographic social realism. Here was working-class northern Britain in decline, shot not in earnest monochrome but, using a ring flash, in gleeful chromatic brilliance — “colour is real, isn’t it? It’s right in your face”, Parr said — and with apparent neutrality, though shooting at close range to plunge the viewer into the picture.

Was Parr cruel, patronising and voyeuristic, or accessible, cheeky and sympathetic to those abandoned by Thatcherism and taking what pleasures remained? The ambiguity holds the gaze, captivates the mind, and assured Parr both prominence and misunderstanding.

When he applied to become a full member of Magnum in 1994, there was loud dissent, Henri Cartier-Bresson saying his work seemed to come “from a different planet” — which was true, except that our planet was beginning to look increasingly like Parr’s images. Parr was elected by one vote, and it soon became clear that “the Martin Parr-ization of the world . . . exploding in colour, tourism and kitsch”, as Swiss photographer René Burri put it, was a prophecy of the 21st century.

“Magnum photographers were meant to go out as a crusade . . . to places like famine and war,” Parr said. “I went out and went round the corner to the local supermarket because this to me is the front line”.

Parr was born in Epsom, Surrey, in 1952, to a Methodist family. His father, a civil servant, was a keen birdwatcher; his paternal grandfather, an amateur photographer with whom he spent holidays in Yorkshire, lent him his first camera. At Surbiton County Grammar he was undistinguished — “utterly lazy and inattentive”, the words of a school report, is the title of his autobiography, published in September. It recounts how the very opposite characteristics, intensive work and obsessive close looking, propelled his career.

He studied photography at Manchester Polytechnic where he met Susie, his wife of 45 years, then worked briefly documenting Butlin’s holiday camps. There he discovered and began collecting John Hinde’s 1960s colour postcards of family fun at Butlin’s, a key influence. Parr was also among the first in the early 1980s to see the scope of applying the brightly lit style of commercial photography to documentary subjects.

He moved in 1982 to Merseyside, then in 1987 permanently to Bristol. His withering The Cost of Living (1989) depicted middle-class affluence — Tory toffs (“Conservative Midsummer Madness Party”), insatiable students (“Strawberry Tea, Malvern Girls School”) — in the Thatcher years. Small World (1995), critiquing mass tourism, and Common Sense (1999), dissecting consumer culture — hamburgers, beaming blue shades in Benidorm — are the most piercingly acute of the numerous photobooks which followed.

In the 21st century he embraced digital and travelled widely. By now the Parr brand was globally renowned, both for his sweet ’n’ sour, satirical/complicit tone, and for his particular definition of what he called “the craziness of the English, with all their hobbies and their interests. The race meetings, the agricultural shows, the summer fêtes.” That he loved all this is obvious from his devotion A woman sunbathing on a blue towel wears blue tanning goggles and bright red lipstick, with her arms resting above her head. the minutiae of these events, and from his lifetime spent recording them.

He was aware too that he was a compromised, even conniving, messenger of global ills: he told the FT in 2007 “I am a great believer in hypocrisy . . . All the things I critique are the things I do myself. My main agenda is the increasing wealth of the west, which is a big problem we have.” That doublespeak lifts his unnerving photographs above moralising, to become memorials to the mores of our times.

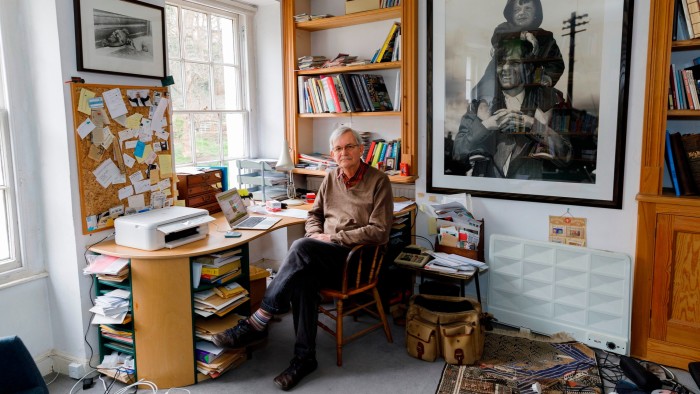

Although not overtly political, Parr believed “all photojournalists are leftwing, you can’t do this job unless you care about people.” The Martin Parr Foundation, established 2014, opened in its own building in Bristol in 2017, supports young photographers, and houses his archives and those of many other British and Irish photographers whose reputations he has helped.

He never lost his democratic sensibility, nor his joy in small things. Diagnosed with cancer in 2021, he photographed the first meal he was allowed to eat after three weeks in hospital: “Tomato soup — I think it was Heinz tomato soup — orange juice and an ice cream. NHS ice cream was surprisingly good.”

Read the full article here