Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the Film myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

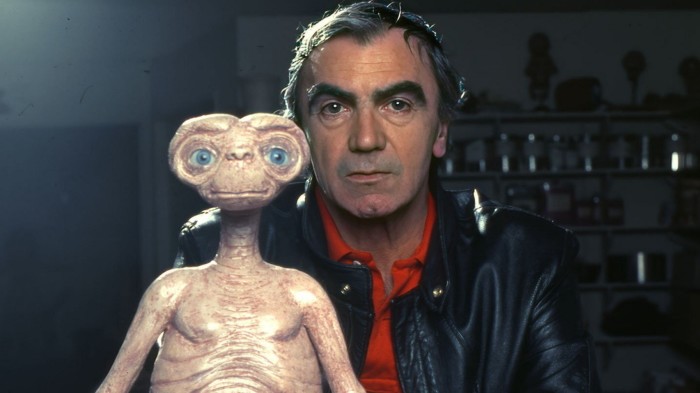

The challenge of special effects is how to enchant an audience while remaining invisible. It is a magic trick where neither mechanics nor magician should ever appear on screen or in the viewers’ minds. The late Carlo Rambaldi was a maestro of such hidden ingenuity. This week New York’s MoMA, in collaboration with Cinecittà, Rome, will be hosting a centennial tribute to Rambaldi’s work, screening blockbusters and curios alike. The films shine light on a three-time Oscar-winning artist, justly venerated in his field, yet one who remains relatively enigmatic; a designer who could create a character beloved by generations of children and also scenes so horrifically realistic that the director faced prison.

Born in 1925 in Vigarano Mainarda, north-east Italy, Rambaldi studied painting at the Academy of Fine Arts in Bologna, leaning towards expressionism and surrealism. His early forays into the film industry involved creating monsters for pseudo-epics based on Greco-Roman myth. Although sword-and-sandal films of that time have their charms, many were simply romantic intrigues with the title creatures as bait. Budgets meant it was often easier to have an actor stumbling around in a latex suit, obscured by smoke and scenery. Rambaldi’s approach was different. His studies of movement and musculature as an artist became crucial, building complex monsters such as the Cyclops in The Giants of Thessaly (1960), who seemed curiously sympathetic.

As hack and slash gave way to slasher, Rambaldi pivoted only slightly. His mythological work had modest eye-gouging gore, which could be ramped up for the emerging giallo movement and beyond. His surrealistic streak served him well as films began to incorporate sinister dolls, automatons and puppets (Dario Argento’s Deep Red, 1975, for instance).

His work in horror extended from the supernatural to the psychological (the tentacled manifestation in Andrzej Żuławski’s Possession, 1981) to the salacious (the bloodbath of Andy Warhol’s rubber-stamped Frankenstein and Dracula films in 1973 and ’74). And there are few greater compliments possible to a special effects artist than to witness your director, Lucio Fulci, hauled before court for animal cruelty. Rambaldi was called to testify in his defence, demonstrating that the scenes of dog mutilation in A Lizard in a Woman’s Skin (1971) were, in fact, artificial.

He adapted his work to fit the coming sexual revolution, though not without satirical edge — creating, for instance, the absurdist sex-dolls in The Wedding March, 1966, by renowned provocateur Marco Ferreri. Rambaldi also crafted the Boschian mechanical devil in Pasolini’s version of The Canterbury Tales, 1972, which lavishly defecates sinners into hell. And his designs for the comic book adaptation Modesty Blaise (1966), the interstellar excess of Barbarella (1968), and the sapphic BDSM-tinged Check to the Queen (1969) possessed pop art glamour and kitsch. Yet it was a vast extraterrestrial skeleton made for the raygun gothic Planet of the Vampires (1965) that would herald the future.

Rambaldi’s Hollywood profile was raised immeasurably by his colossal 40-foot 6-ton mechanical hulk for King Kong, 1976 (the artist compared its construction to the space programme). It boasted a hand large enough to grip lead actress Jessica Lange, and a face that could convey multiple feelings — though it ended up appearing on screen for only 15 seconds. Yet Rambaldi’s sense of emotional range and illusion of depth appealed to Steven Spielberg, who utilised the artist’s talents for Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) to convey the strangeness and benevolence of the visitors. Their next collaboration would be E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (1982): extraterrestrial wonder packaged into a stratospherically successful family film.

If Spielberg’s aliens were designed to bring us fuzzy feelings of universal sentimentalism, Ridley Scott had something very different in mind. Alien (1979), for which Rambaldi channelled HR Giger’s nightmarish designs into the xenomorph’s animatronic head, aimed to terrify viewers with a vision of celestial nihilism but also confound them with a creature whose mystery, like the universe, just kept unfolding.

It’s hard to believe the xenomorph and E.T. are the work of the same person. Yet they have much in common in their meticulous animatronics — if “Rambaldi was E.T.’s Geppetto”, as Spielberg acknowledged, then he is also an incubator of the xenomorph. Inspired by Rambaldi’s Himalayan cat, E.T.’s acutely rendered mannerisms and large glass eyes appeal to our nurturing instincts (as a child, I was utterly convinced it was real, and the prop was treated as such on the set). It took an entire team of puppeteers to operate E.T.’s approximately 150 different facial movements via remote control and pneumatics.

The xenomorph is just as meticulous, its features and movements invoking fight-or-flight responses, but also a sense of obscenity. Here, a system of hand-operated cables was built within the head to move various parts including the bizarre inner jaw. (Rambaldi complained Scott only used around 20 movements out of a possible 100.) Copious quantities of K-Y Jelly were employed as xenomorph drool, to add to the grotesque revulsion and, practically, to conceal moving parts. Stretched condoms served as membranes in the monster’s mouth.

Both E.T. and the xenomorph are essentially complex machines encased in materials like fibreglass and polyurethane. Yet they commanded adoration and terror respectively. They worked not only because Rambaldi and his team were masterfully operating his creations, but because they were masterfully operating the viewer.

Rambaldi’s filmography is a cornucopia of the strange and wonderful: the vampire bats of Arthur Hiller’s Nightwing (1979), the sandworms for David Lynch’s adaptation of Dune (1984). In his later years, he lamented the misuse of CGI. “Any kid with a computer can reproduce the special effects seen in today’s movies. The mystery’s gone,” he said. “It’s as if a magician had revealed all of his tricks.”

The lesson of Rambaldi is that you only get out what you put in, not simply in terms of the productions and technologies, but a deep curiosity: how something moves and feels. If characters are to have soul, you must believe your audience possesses them.

December 10-24, moma.org

Read the full article here