Tate has announced a spectacular gift of art works and supporting finance from collector, philanthropist and real estate mogul Jorge M Pérez.

The centrepiece of the gift is a vast triptych by the American abstract expressionist Joan Mitchell, measuring six metres in length and titled “Iva” (1973), after her much-loved Alsatian dog. Tate director Maria Balshaw has described the donation as “transformational” and “an act of incredible generosity”. The value of the mighty painting is undisclosed but Mitchell’s auction record, set in 2023 for a smaller single work, stands at $29mn.

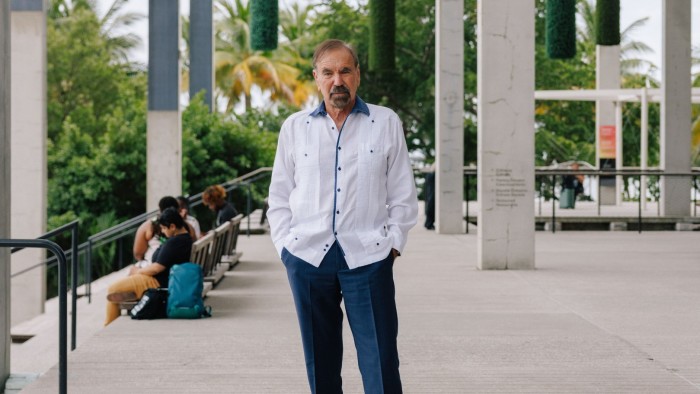

“It was in our bedroom,” Pérez says over a video call from Miami, Florida, where his real estate and other businesses are based. “We made the wall of our bedroom larger so it could fit. It was a painting we loved, particularly my wife — she was almost crying when we made the decision.”

Darlene and Jorge Pérez are, however, determined that the works in their collection of more than 5,000 pieces should be dispersed to public institutions, including the Pérez Art Museum Miami (PAMM), renamed for its benefactor in 2013 after his gifts of art and resources which now total more than $100mn — “for future generations and for the most people possible to see them and enjoy them, and for art to contribute to their lives as it has contributed to mine”, he says.

From today the Mitchell triptych is on display at Tate Modern in a room next to the Seagram Murals by Mark Rothko, a leading light of the abstract expressionist school. Asked why he chose London’s Tate for this gift, Pérez replies: “I like the idea of expanding the global art experience. We have plenty of abstract expressionists across America but Tate didn’t have so many, and the interaction between the Rothkos and Joan Mitchell will be fantastic — two of the greatest abstract expressionist painters.”

The American artists of that post-war school, who rose to mainstream acceptance in the 1950s and 1960s, were famously reluctant to value the women in their midst — though Mitchell was one of the more commercially successful in her lifetime (she died of cancer in 1992).

Mitchell was “probably the first of the important women to be recognised, along with Lee Krasner, Grace Hartigan, Elaine de Kooning. They were all as good as any man, if not better, but it has taken some time for the world to understand how great these artists are. They’re not great women painters, they’re great painters,” Pérez says.

Other personal enthusiasms shape Pérez’s donation to Tate. It includes an endowment to support curatorial posts and research, given through the Pérez family’s philanthropic foundation; again, the amount is unspecified. The main purpose is to further specialist knowledge of African and Latin American art, two of his passions. In the early days, he says, his collection was entirely of Latin American works — “because that is our heritage” — and an absorption with art from the African continent followed.

Further gifts to Tate “in the near future” will include African works from such important artists as El Anatsui and William Kentridge and photographers Malick Sidibe and Seydou Keita, to be followed by Latin American works from leading names.

“I hope to expand the world’s knowledge of African art, after that we’ll do the same with Latin American art — in the hope that art from this continent gets a wider audience.”

As with the great US artists, these are areas in which Tate’s collection is far from rich. It is hard to overstate the importance of such gifts to Britain’s public galleries, which have neither the hefty endowments of many US institutions nor the substantial governmental support of others elsewhere in Europe. About 30 per cent of Tate’s income comes from government grants, while the remaining 70 per cent depends on fundraising, tickets and other sales: it is still struggling with a post-pandemic deficit and there have been sweeping job cuts. Recent highly publicised controversies over the source and acceptability of corporate funds have made the situation considerably more tricky.

Perhaps most significantly, Tate has no dedicated acquisitions budget at all: every purchase has to be individually supported in some way; in recent years, artists themselves have made donations of their own works. In such a context, stellar pieces such as the Mitchell triptych would be stratospherically out of reach if it were not for private generosity.

At 75, and despite the energetic dispersal of his collection, Pérez is unstoppable in acquiring more work. “I’m more like a heroin addict, only I’m an art addict,” he says. “We follow the galleries and fairs, the auction houses, all over the world — we spend probably a third of our time travelling for art, visiting studios, learning more.”

Yet despite the broad international range of Pérez’s philanthropy in art, Miami is still home. Besides his largesse to PAMM, in 2019 he founded a huge not-for-profit contemporary art space in Miami, El Espacio 23, which hosts free exhibitions and projects based on his collection, and the city is central to his plans for the future.

“I think the majority of the art will remain here, because I hope Miami becomes not just a business and tourist centre but an artistic centre too. Apart from a few pieces that my children want, all of it will be going to museums, it’s all meant for the public to access. When I finish, we will not own any art.”

Joan Mitchell’s ‘Iva’ is on free display at Tate Modern, tate.org.uk

Find out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend on Instagram and X, and sign up to receive the FT Weekend newsletter every Saturday morning

Read the full article here