Springtime is finally here, in the northern hemisphere at least, and with it has come a burst of books about the joys of exploring, restoring and understanding the natural world. Each reveals how satisfying, yet testing, these endeavours can be.

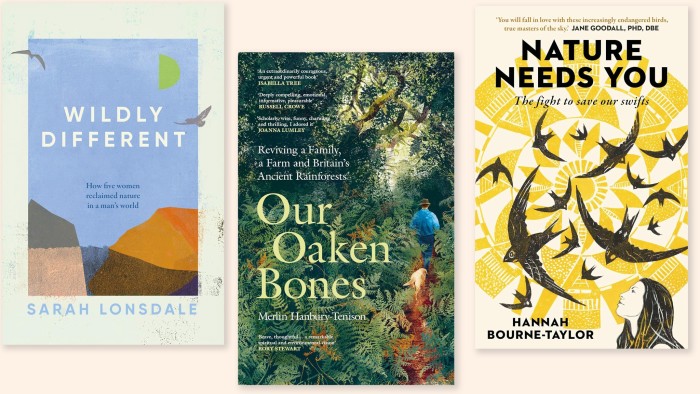

Former soldier, Merlin Hanbury-Tenison, charts some rough terrain in his memoir, Our Oaken Bones: Reviving a Family, a Farm and Britain’s Ancient Rainforests (Witness Books £22). Russell Crowe is among the blurbers of this tribute to the restorative powers of the wilderness and Hanbury-Tenison himself once dabbled with acting: he played Crowe’s son in the 2000 film, Proof of Life.

But he ended up in the army and, at the age of 21, was doing his first tour in Afghanistan, where his tank ran over a landmine. He was unharmed physically but years later in 2017, having left the army for a management consultancy in London, he had a breakdown.

Diagnosed with complex PTSD, he fled to Cabilla, the Cornish hill farm his father, the explorer Robin Hanbury-Tenison, had bought in 1960. Its patch of ancient rainforest proved an unexpected saviour for both Hanbury-Tenison and his wife, Lizzie, who had suffered repeated miscarriages.

They set up a wellness retreat and a charity to preserve their rare ancient woodland, along with a way of life few urbanites know. Hanbury-Tenison’s description of how he stalks, shoots and guts roe deer is memorable. “The guts, stomach, liver and kidneys come out first,” he writes, then the lungs, heart and oesophagus.

The idea that such exploits are the preserve of men, not women, is brilliantly dispatched by British journalism lecturer, Sarah Lonsdale, in Wildly Different: How Five Women Reclaimed Nature in a Man’s World (Manchester University Press £20).

Female explorers, scientists and conservationists, Lonsdale reveals, have been defying the expectations of their gender for far longer than most imagine. Her story is told through the lives of five remarkable women, including Mina Hubbard, a young Canadian widow who braved bears, starvation and freezing rivers to map the wilds of Labrador in the early 1900s.

There is also Ethel Haythornthwaite, who devoted her life to saving the wilds of the UK’s Peak District; mountaineer Dorothy Pilley and entomologist Evelyn Cheesman. Her fifth subject is Kenya’s Wangari Maathai, founder of the Green Belt Movement to slow desertification and plant millions of trees. All faced huge obstacles, not least the attitudes of male adversaries such as British explorer George Curzon. He dismissed the thought of women being accepted into the Royal Geographical Society of Britain since they were incapable of contributing to scientific knowledge and “their sex and their training render them equally unfitted for exploration”.

Things have moved on in the 21st century, as conservationist Hannah Bourne-Taylor, aka the naked bird girl, reveals in Nature Needs You: The Fight to Save Our Swifts (Elliott & Thompson £16.99). In November 2022, she went to Hyde Park Speakers’ Corner, painted head to toe in feathers and wearing only boots and a thong, to highlight the declining number of swifts. Populations of the migratory birds had stabilised in places that had encouraged the use of swift bricks, hollow bricks they can use to nest in buildings.

Bourne-Taylor wanted to highlight the 100,000 signatures needed on a parliamentary petition to make the bricks compulsory in new homes and create a widespread nesting habitat. The BBC covered her effort, as did Piers Morgan and, despite the trolls who told her she deserved to be gang raped, the 100,000 signatures were eventually obtained.

Alas, this proved to be just the start of a maddening cycle of elation and despair as Bourne-Taylor and her allies, including former Conservative environment minister, Zac Goldsmith, struggled with the thickets of Westminster and Whitehall. Despite repeated official assurances, and wide support from MPs, a mandate for swift bricks in new homes remains elusive.

Things end more happily in Hannah Dale’s charmingly illustrated A Wilding Year: Bringing Life Back to the Land (Batsford £14.99). Dale is a wildlife illustrator and in 2015, her husband Jack inherited Low Farm, a small property in Lincolnshire. The couple spent a few years trying to coax the stubborn ground to produce profitable harvests before Jack read Isabella Tree’s prizewinning book Wilding. Inspired by its story of a failing Sussex farm transformed into a rich habitat, the couple took in their last harvest in 2019 and, in Dale’s words, “stood back to see what would happen”.

The effort was not always smooth. Neighbours were offended to discover the couple planned to plant 27,000 trees around the farm’s perimeter, in part to ward off concerns the rewilded acres would spread “weed” seeds.

They fought on and created a haven that Dale describes as being filled with an explosion of birdsong, where hedgerows are festooned with blossoms while “the soils crawl and the grasses fizz with insects”. It’s an inspiring story about how quickly the untamed world can recover once it is, at last, left alone.

Join our online book group on Facebook at FT Books Café and follow FT Weekend on Instagram and X

Read the full article here