Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Julius Caesar hustled for a succession of public offices during his rise to power because he needed to secure immunity from prosecution. Augustus, a careful curator of his image, wore platform shoes to look taller, while the shortlived emperor Otho covered his bald patch with a hairpiece. Domitian, who terrorised Rome’s Senate as he sank into paranoia, used to sit in solitude stabbing flies to death with a sharpened pen.

Or so Suetonius tells us in his scurrilous, meticulously detailed The Lives of the Caesars — written in the second century AD, when gossip was still swirling about the personal foibles, public acts and private perversions of the 12 men who had come to epitomise imperial power over the course of 150 years.

There is plenty of contemporary resonance in this new translation by Tom Holland, the historian and podcaster — published by Penguin just as a modern-day strongman swaggers back on to America’s political stage, threatening to bulldoze its constitutional boundaries. But if Suetonius’s Caesars seem familiar, it is also — as Holland puts it — because he gave us “the model of how to write the biography of a great ruler”.

A well-connected official who served as private secretary to Hadrian, Suetonius drew on a multiplicity of sources — letters in Augustus’s own handwriting from the archives, public inscriptions from the provinces, his father’s reminiscences of military service under Otho and the many anecdotes and jokes in public circulation.

He did not seek to give a chronological account of events. Instead, after setting out the essentials of family origins and career, his pen-portraits are organised by theme — covering each ruler’s admirable qualities before turning to their flaws; listing their public building works and legislative ventures, but also their sexual preferences, favourite gladiators or chariot teams, and the omens that presaged their rise or fall from power.

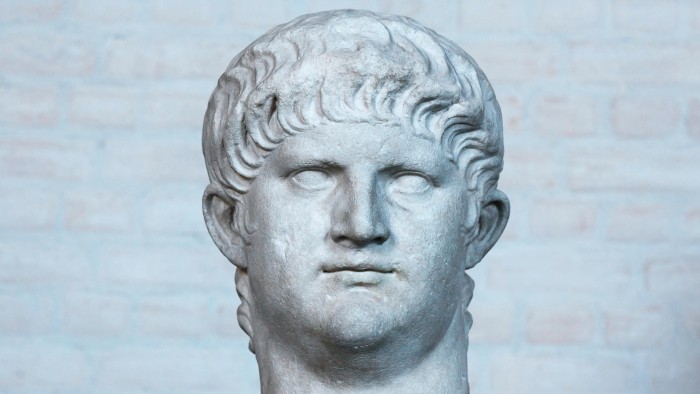

The results can be baffling: how to reconcile the Nero who had funded new, fire-resistant building designs with the arsonist who sang as the city burned? Or the Vitellius praised as an honest provincial administrator with the dissolute flatterer reviled in Rome, racing chariots with Caligula and serving flamingos’ tongues at his banquets?

But the Lives are full of wonderfully immediate details and vignettes. There is Augustus fussing over his grandchildren’s handwriting and teaching them to swim. There is the frugal Tiberius serving half a wild boar at a feast. And there is the unpretentious Vespasian bursting out laughing when people try to curry favour by tracing his family back to Hercules. And even if Suetonius is sometimes defeated by his conflicting sources, read in totality, the Lives give a coherent, sweeping account of how autocracy took root in the Roman state.

Above all, the book shows the sheer theatricality it took to sustain an imperial image. Each Caesar can be judged by the scale and character of the hunts, fights, races and naval battles they staged. Nero held races of camel-drawn chariots; Caligula transgressed social norms by fighting in gladiatorial contests himself; Domitian had a spectator thrown to the dogs for a passing comment.

All the spectacle took money and military backing, however. The Caesars are constantly running up debts, extorting legacies and sequestering their enemies’ estates to pay for the shows, largesse and the legions. Vespasian — both less aristocratic and less ruthless — is the only emperor so undignified as to profit from trade, while clamping down on corruption and raising taxes — including on urine. His probity won him ridicule.

In much of this, Suetonius’s world is one we can recognise. But the values and the pervasive violence that underpin it can be deeply alien. The poisonings and murderous intrigues that convulsed the imperial families, the persecutions the Caesars carried out against suspected plotters, are meant to seem monstrous. But Suetonius praises decisions to enforce discipline among the legionaries by decimation; or to punish a lapsed Vestal virgin in the traditional manner by burying her alive.

Otho redeems himself at the last by a decisive suicide. Nero’s degeneracy is made clear by his fear and hesitancy in slitting his own throat. After Nero’s death brought the empire into new convulsions, though, most Romans had had enough of violence. Vitellius, striding over a blood-soaked battlefield, revolted his companions by telling them a dead enemy “smells sweet”. The overriding argument in favour of installing a new emperor was clear. A cruel, capricious Caesar was better than civil war.

The Lives of the Caesars by Suetonius, translated by Tom Holland, Penguin Classics £25, 448 pages

Delphine Strauss is the FT’s economics correspondent

Join our online book group on Facebook at FT Books Café and follow FT Weekend on Instagram and X

Read the full article here