Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

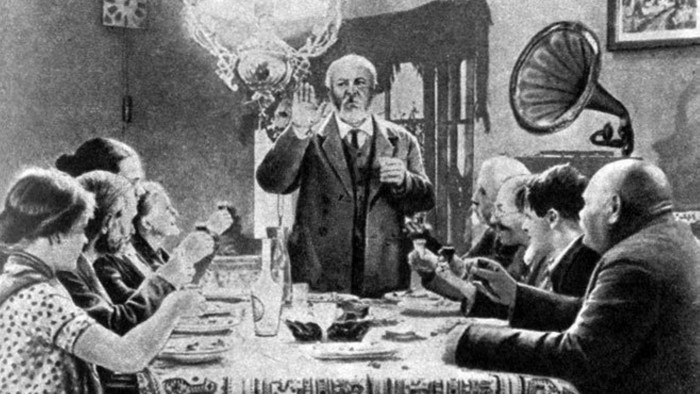

Counterplan opened on November 7 1932 — the 15th anniversary of the October revolution — to mostly glowing reviews (there was, at this point, still wriggle room for artistic criticism in Russia). Officialdom jumped on the propagandist potential of its central song, flogging it mercilessly on the radio and printing the sheet music in a state newspaper. It became a staple of state festivals and functions. But, more than that, its sheer, ear-worming ubiquity gave it quasi-folk status — the first song in Soviet Russian cinema to fly off the screen and into the daily soundscape of Soviet life.

And it began to spread abroad, at first in contexts that mirrored its leftist origins. “Allons au-devant de la vie” (“Let’s go meet life”), with new lyrics by Jeanne Perret, became an anthem for the burgeoning French youth hostel movement. It was recorded by the Chorale Populaire de Paris, a workers’ choir devoted to “beautiful music and social progress”, and featured in Jean Renoir’s 1936 propaganda film for the French Popular Front La vie est à nous. (The director for that performance, Suzanne Cointe, was later guillotined by the Nazis.) In 1939 Nancy Head, co-founder of the UK Workers’ Music Association, published a version in English under the title “Salute to Life”. This was performed by the BBC Symphony Orchestra and Henry Wood at the Royal Albert Hall in December 1941, part of a concert celebrating Stalin’s birthday.

Which raises the question: how did this composer of “serious” music feel about his biggest hit, a populist song from an agitprop film that eclipsed his other works? Shostakovich went to great efforts to compose this spontaneous-sounding gem (“I worked hard a lot on it, making 10 variants, and only the 11th satisfied me,” he said), suggesting a sense of care and ownership. Moreover, the success of Counterplan marked a turning point in his film-music career, which would sustain him and his family during periods of disfavour, when other sources of income had dried up. Some have even suggested that the song — a favourite of Stalin’s — kept him alive during the great purge, though it didn’t save lyricist Boris Kornilov, who was executed in 1938.

Scholars have pored over Shostakovich’s own recycling of the song — in his score for the 1949 biopic Michurin or in his 1959 operetta Moscow, Cheryomushki — looking for coded commentary in the tune’s triumphalism. As with much of Shostakovich’s output, the meaning is ambiguous, often in the ear of the beholder — and always second to the music itself.

Let us know your thoughts on ‘The Song of the Counterplan’ in the comments section below

The paperback edition of ‘The Life of a Song: The stories behind 100 of the world’s best-loved songs’, edited by David Cheal and Jan Dalley, is published by Chambers

Music credits: Naxos; Foyer

Read the full article here