Few if any non-fiction books have given more joy over the past 75 years than Ernst Gombrich’s The Story of Art, an unlikely bestseller when it appeared in 1950 and, 8mn copies later, the most popular art book of all time.

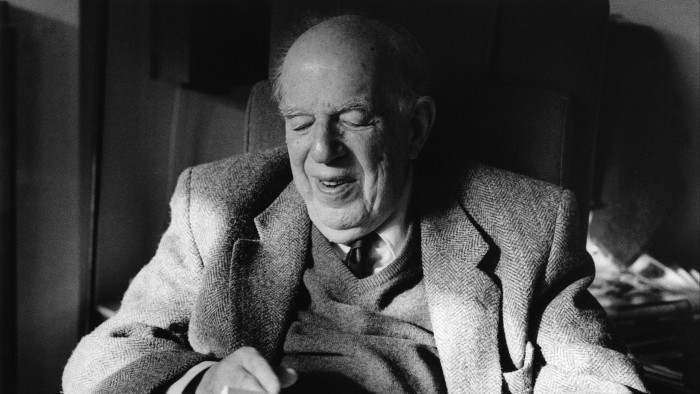

Gombrich, a Viennese émigré working at the University of London’s Warburg Institute, received a £50 advance from fellow émigré Béla Horovitz’s Phaidon press and, struggling to complete the book, repeatedly tried to return the money. He lived to see 16 editions before his death in 2001; of all titles published in 1950, only The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe has outsold The Story of Art. Gombrich made art history as enticing and exotic a land as Narnia, and was its lucid, charming guide. “Like millions since, I felt I had been given a map to a great country,” recalls Neil MacGregor, former director of the National Gallery and the British Museum.

The Story of Art is a classic of postwar democratisation, opening up art history to wide audiences in a country which didn’t then teach it in public universities — and of postwar optimism. It was one of a crop of bold generalising studies — Kenneth Clark’s The Nude (1956), FR Leavis’s The Great Tradition (1948), Lionel Trilling’s The Liberal Imagination (1950) — which, in the aftermath of atrocity, sought to restore ideas of unity and cohesion, the human image and the human imagination, to western culture.

All have long been criticised as elitist and patriarchal — what Mary Beard calls Clark’s “one damn genius after the next” approach — but Gombrich, although he too excludes women artists (eventually he added a sole woman artist, Käthe Kollwitz, in later editions) and is proudly Eurocentric, never fell from fashion. On its 75th birthday, The Story of Art speaks powerfully to today’s fractured cultural landscape, and reads as freshly as ever. Why?

First, it is a masterpiece of storytelling, unfolding artist by artist how “people strove for certain aims and passed on their achievements”: “a living chain of tradition” linking “the art of our own days with that of the Pyramid age”.

Second, Gombrich casts that tale in the winning mode of capitalism triumphant: his chronology of human challenge and ingenuity parallels Joseph Schumpeter’s innovation-oriented economics, as each artistic generation identifies and solves problems which in turn open opportunities for the next — the creative destruction of Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy (1942). Gombrich’s famous opening lines, “there really is no such thing as Art. There are only artists”, declares individualism pivotal, and comes exuberantly to life in the initial contrasting illustrations: Dürer’s exquisitely realistic “Young Hare” (1502), Picasso’s screeching cartoonish “Cockerel” (1938), exultant in “its aggressiveness, its cheek and its stupidity”.

What follows is a rollercoaster of ruthless competition between individuals and cities — Ingres versus Delacroix, Renaissance Rome versus Florence versus Venice — against a backcloth where free movement of ideas and people is key to change and innovation: Bernini’s baroque spreads across Europe, Manet invents modernism in Paris after discovering Goya in Spain.

Third, while the story is upbeat — “The Great Awakening”, “The Conquest of Reality” are typical chapter headings — it is the more exciting for having a villain, and one we recognise: political attempts to confine and control art. Gombrich, an anti-Marxist refugee of totalitarianism, was writing against the cold war, but this strand is still pertinent as museums increasingly display the past through a political lens. (Sonia Barrett’s smashed up “Chair no 35”, 2013, plonked centrally in Tate Britain’s Canaletto and Hogarth gallery to remind us that “English furniture in the 18th century was often made from mahogany produced by enslaved people in the Caribbean”, is the notorious symbol of this idiocy.)

Gombrich is never strident but a few pages into his introduction, two versions of Caravaggio’s “St Matthew” writing the Gospel — a dazzlingly original depiction of a dirty, awkward peasant being taught how to hold a pen by a beautiful fat-fingered child-angel, and a conventional rendering of an elderly saint inspired by an angel flying above — illuminate the message. The latter still hangs in Rome’s San Luigi dei Francesi (its Caravaggio paintings recently made famous as favourites of the late Pope Francis), but it was Caravaggio’s second attempt — the Church rejected the brilliant first painting as irreverent, indecorous: an example of institutional stifling of artistic expression. The poignant sequel is that the first “St Matthew”, bought for Berlin, was destroyed in 1945.

Awareness of the fragility of culture underlies Gombrich’s whole endeavour. Born in 1909 in a sophisticated Jewish family (though recently converted to Protestantism), friends with Mahler and Freud, he settled in England in 1936; during the second world war he monitored German propaganda broadcasts for the BBC, realising when Bruckner’s 7th Symphony — composed as a memorial to Wagner — came on the air, that Hitler was dead.

According to his son Richard, Gombrich “felt that one of the chief blessings of British society was that few people were interested in or swayed by political or religious ideologies”. The Story of Art fuses English empiricism and narrative tradition with central European conviction in the absolute value of high culture.

From this background, Gombrich warned that “dehumanising the humanities can only lead to their extinction”; he answers with his own empathetic humanity. Open the book at random and you plunge into an individual’s dilemmas and hard-won solutions. Van Eyck learns oil painting, glazes, pigments, and suddenly “here it all was — the carpet and the slippers, the rosary on the wall, the little brush beside the bed” of “The Arnolfini Marriage” (1434), “the real world . . . fixed on to a panel as if by magic”. Vermeer proceeds from Dutch realism through softened contrasts, blurry outlines, to a particular, hypnotic “mellowness and precision”.

So Gombrich celebrated “objects made by human beings for human beings”, physical, tactile — refreshing amid our online image saturation and noisy conceptual art industry. He brings us close to a work’s physical presence, the canvas surface — Van Gogh “subtle and deliberate . . . even in his strongest effects”; Watteau’s delicate brushwork, refined harmonies “not easily revealed in reproductions”, living flesh conveyed in “a mere whiff of chalk” — while acknowledging art’s ultimate mystery: “one cannot explain the existence of genius. It is better to enjoy it”.

Gombrich’s certainties — “the most famous works are really often the greatest”; Greece 520-420BC saw “the greatest and most astonishing revolution in the whole history of art” — go against relativism, horror of exceptionalism and the mire of theory in current academic art history. His fear of late capitalist cheap sensationalism — “if anybody needs a champion today, it is the artist who shuns rebellious gestures” — conflicts with today’s museums as theme parks. Half a century of valiant challenges — from John Berger’s Marxist Ways of Seeing (1972) to Katy Hessel’s The Story of Art without Men (2022) — show that Gombrich’s view of art is not the only one. But no writer is a more pleasurable and vital counterforce to intolerance and today’s dangerous politicisation of culture.

Find out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend on Instagram, Bluesky and X, and sign up to receive the FT Weekend newsletter every Saturday morning

Read the full article here