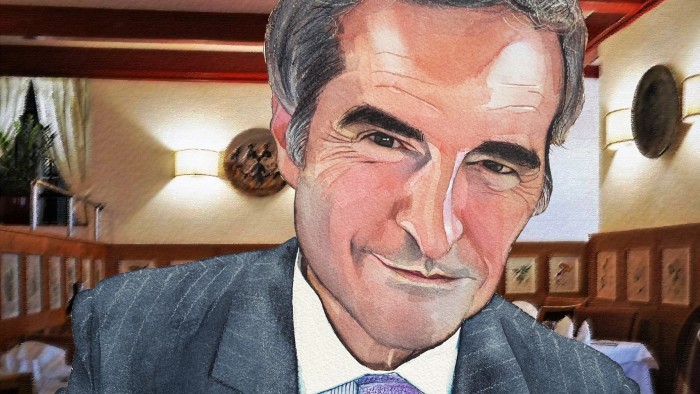

Rafael Grossi, head of the International Atomic Energy Agency — thus the world’s nuclear policeman — stabs two points with his knife into a white tablecloth.

“This is Moscow,” he says. “This is Kyiv.” Then he gestures between the two and marks Zaporizhzhia, a gigantic Ukrainian nuclear plant; this used to provide a fifth of the country’s electricity but has been occupied by Russian soldiers, making it one of the first civilian nuclear plants to be attacked in war.

“There is much more bombardment there now, and the Russians are pushing hard,” Grossi says, explaining that a rotating IAEA team has been present since 2022, in a bid to prevent another Chernobyl-style disaster. “It’s dangerous. But we have to be there,” he adds, revealing that he has made five trips himself — under direct gunfire.

As I listen, I feel cognitive dissonance. We are meeting in Ristorante Sole, one of Vienna’s more glamorous restaurants and a place that feels timelessly peaceful amid the elegant, sunshine-dappled streets and chiming sounds from ancient clocks.

However, Grossi, 64, is grappling with something that hovers over us all, even though we normally ignore it. As depicted in Nuclear War, the recent bestselling book by Annie Jacobsen, it is the risk that an accidental or deliberate nuclear disaster could (at best) contaminate regions or (at worst) destroy civilisation.

That is in part because Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine has put civilian nuclear plants in the line of fire; meanwhile Vladimir Putin has repeatedly threatened to use nuclear weapons. “This is worrying because it normalises this,” Grossi admits with masterly understatement. “In the past, this was quite taboo, but now people talk about tactical nuclear weapons like something which could be contained or permissible.”

Grossi also faces a nuclear-armed North Korea, rising tensions between India and Pakistan, both nuclear powers, and his “biggest preoccupation”: Iran. According to a new and confidential IAEA report, the latter has dramatically increased its stockpile of uranium enriched close to weapons grade — and meanwhile Israel is threatening attacks. Earlier this year, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists decreed that the world is now a mere 89 seconds to midnight on its Doomsday Clock.

But there is a profound irony too: just as these existential threats worsen, Grossi is facing surging enthusiasm for nuclear power generation, since policymakers are realising that it could be a potent “green” source of power for digital tech. Thus while nuclear presents huge peril, it also offers extraordinary promise. Which of these paths is taken now rests with our political leaders — as well as the diplomatic skills of Grossi.

So, I wonder, as we sit down to lunch, is he intimidated by this responsibility? He shrugs — and ducks. “I am a calm person. I focus on what I can do.”

He selected the restaurant because he loves the nearby opera house, and the Italian cuisine here chimes with his heritage. Although he was born in Argentina, his family hails from Italy, like over half of the Argentine population. It shows: a wiry man, Grossi is sporting a suit as stylish as anything seen in Milan, and has bracelets under his cuff from the 2022 Fifa World Cup in Qatar. He is football mad, he explains, and having watched Argentina win there in a penalty shootout, “I won’t take them off until the next World Cup.”

What happens, I ask, if Argentina play Italy? “It is Argentina — but I support Italy otherwise,” says Grossi, who speaks Spanish, Italian and four other languages.

In every other part of life, however, he strives to be non-tribal, as befits a career diplomat. After studying political science, he represented Argentina in numerous missions, including stints as chief of staff to the IAEA and the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons. Then, in 2019, he became the sixth director-general of the IAEA (a UN agency) since its founding in 1957, overseeing some 2,500 staff.

He is supposed to be at the IAEA for a couple more years, but tells me that he is bidding to become UN secretary-general when the position becomes available next year. “I am not going to campaign — my work is my campaign,” he says. “The UN is in a very bad place at the moment — the original idea is valid, but it has become big and bureaucratised and absent from the resolution of major international crises. It doesn’t need to be like that.”

Grossi has the right training — and Rolodex. He arrives carrying two mobile phones. “One public and one private — but that is meaningless since with the politicians they all want to be on your private [one],” he chuckles. “Signal is also very popular with politicians — but after what happened in the States [when top US officials accidentally shared classified information with a journalist via Signal messages], who knows?”

We laugh, and the restaurant owner — a voluble Macedonian called Aki Nuredini — arrives to discuss the menu in rapid-fire Italian. Grossi notes that celebrities ranging from Bill Clinton to Plácido Domingo have all eaten here but admits “I don’t eat much lunch normally” and “never drink alcohol except at the weekend”, since he is obsessive about keeping fit.

We duly ignore the wine list and, on Nuredini’s advice, decide to share salt-baked branzino, grilled vegetables and tomato salad. A bowl of hot focaccia, scattered with rosemary, appears. I nibble and note that it is delicious. Grossi ignores it.

As we wait for the fish, Grossi reveals that he has just returned from a visit to Italy to promote civilian nuclear power. Next, he is heading to both Kyiv and Moscow, to discuss Zaporizhzhia.

Could that plant produce another Chernobyl-style accident? In recent months, Grossi has engaged in shuttle diplomacy with both Volodymyr Zelenskyy and Putin, meeting the Ukrainian president “many times” — and the Russian president twice, while speaking “a lot” to Putin’s team.

But progress is tough. Grossi explains that the IAEA monitoring team in Zaporizhzhia have travelled there via Ukraine, to underscore its rightful sovereignty, but that means crossing front lines. “It’s dramatic — you cross a bridge, and walk and then climb a rope,” he says. “I have done it before . . . but the Russians are saying now that if you come, you will be killed, probably.” By whom? “We never know really who is shooting,” he says, diplomatically.

The “good” news, apparently, is that the plant, with its six 1,000 megawatt turbines, is “cold”, in scientific parlance, ie not active — so if it is hit, the contamination is unlikely to spread as far as it did after the 1986 Chernobyl accident. “It is not something people should be worried about in Europe,” Grossi says. However, there are supplies at the site which, if hit, could leak and contaminate the local region. “We have to make it without anything big until the ceasefire — until [then] anything could happen.”

Grossi’s even bigger concern is Iran. During the Obama years, Tehran let IAEA inspectors into its nuclear sites and agreed to tight restrictions on its nuclear ambitions in exchange for the lifting of some US sanctions. But in 2018, during Donald Trump’s first term, the deal was ripped up, and the latest IAEA report reiterates that Iran has put restrictions on its inspectors and now has a huge — and swelling — pile of uranium enriched to 60 per cent purity. “Iran doesn’t have a nuclear weapon at this moment, but it has the material.” A bomb could emerge very swiftly.

Trump’s special envoy Steve Witkoff has reopened talks. But Israel’s threats mean that “the Iranian thing has incredible potential to become catastrophic. If there is a failure in negotiation, this will imply most probably military action.”

Worse, Iran’s nuclear capabilities could not be destroyed with a single surgical strike. “The most sensitive things are half a mile underground — I have been there many times,” he says. “To get there you take a spiral tunnel down, down, down.”

Can he prevent the Israelis from launching a potentially “catastrophic” attack? Grossi is encouraged that the Americans and Iranians are at least talking; after we meet news reports suggest that Witkoff even floated outlines for a deal. But since then both Trump and Iran’s supreme leader have made belligerent statements.

Many of the president’s critics say that Witkoff, a former property developer, lacks credentials. But Grossi demurs. “I have seen cases where countries have to be convinced they want to negotiate. But here it is not the case — the talks are very serious,” he says. “Witkoff is an extremely serious person — I don’t subscribe to the idea that he is not. I cannot express [political] preferences, because I work with Democrats and Republicans, but what I can say is that [Trump] has triggered negotiations where there were none before, and this is objectively commendable.”

The sentiment seems to be reciprocated. In office, the Trump team has tried to undermine — or defund — many UN agencies. However, the IAEA has been spared, either because Trump is prioritising the threat or because he wants to encourage the use of civilian nuclear power. Or both.

Either way, Grossi remains intent on talking to everyone — even if they blame him for the actions of their foes. “The Koreans depict me as a shark,” he says. Grossi is controversial there because South Korea dislikes debate about North Korea’s bomb. China was also furious when in 2023 Japan started to release treated water from the wrecked Fukushima nuclear plant into the sea — a dispute that Grossi partly resolved by using Chinese inspectors in Fukushima.

Our fish arrives under a dramatically flaming dome of salt. A waiter fillets it and places it on our plates, drizzled with olive oil. It is fresh and subtly fragrant. So, too, are the grilled vegetables.

What leverage, I ask, do you have in these talks? Grossi says it lies in being a referee: no promise has any credibility without an IAEA report. That means he is constantly on the road. “I pay [a] price with my life, with a divorce,” he observes. He has seven daughters and one son from two marriages. “So many women!” Did that teach you diplomacy? He laughs.

Arguably the only leader on the world stage who refuses to talk to Grossi is North Korea’s Kim Jong Un. “They kicked us out in 2009. But we used to inspect those facilities, so we know that North Korea has nuclear weapons — 60 to 70 warheads, or so.” The basic safety risks concern him deeply, since they “have no interaction with anyone”. He also worries about an accidental or deliberate action that could lead to disaster, like the scenario outlined in Nuclear War where misunderstandings destroy the planet in a couple of hours.

Has he read that book? “No. But I hear it is quite realistic.” So how does he sleep at night? Grossi pushes his fish across his plate — and points out that diplomacy has worked to avoid this, thus far.

“Today we could have 30 countries which could have nuclear weapons, judging from their technical development, but we have nine.” He knows this could rise: if Iran gets a bomb “you could have a cascade in the Middle East”; if Trump withdraws security guarantees from Europe, Poland might move that way too. “This is incredibly dangerous,” he says. “But I believe at the bottom there is always some rationality — before there has always been a moment [to stop] before it is too late. But that requires interlocutors.”

Naive? Maybe not. Grossi became a diplomat in the 1980s, just after Argentina’s military leaders were forced to step down — and shocked the world by revealing a secret nuclear programme in Patagonia. Argentina and Brazil had already begun an arms race. But then, against the odds, clever diplomacy saved the day. “There was a dramatic moment when the Argentinian president invited the Brazilian president to the secret facilities,” he recalls. “It was amazing, like Netanyahu inviting the Palestinians.” So Grossi decided to dedicate his life to non-proliferation, spending a year working inside the nuclear industry — before taking the path that led to the IAEA.

Our fish is cleared away, desert is offered — and rejected. Instead Grossi orders a mint tea, and I take a double espresso.

To lighten the mood, I ask about the second half of his job: promoting safe civilian nuclear use, or “atoms for peace”, as the IAEA tag goes. Until recently, this seemed almost as hard as fighting proliferation, since in the late 20th century there was strident opposition to nuclear power from groups including CND. Thus Germany — and, ironically, Austria, home to the IAEA — shunned nuclear tech. Indeed, when I first met Grossi at the 2021 UN climate talks in Glasgow, he spoke to me on stage, amid jeers from green activists. “They laughed at what I said — do you remember?”

But Trump has just issued a series of executive orders that double down on nuclear energy in America, and even Germany is lessening its opposition. Why? One factor is that tech advances — such as those developed by Bill Gates — are beginning to address the problem of nuclear waste. Another is the advent of smaller and cheaper plants, known as Small Modular Reactors (SMRs). A third is a rising recognition among politicians that it will be tough to decarbonise rapidly without using nuclear energy. Fourth: the younger generation seems to view the sector more positively than my generation, who were raised reading dystopian books like When the Wind Blows.

Is that because memories of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima have faded? Grossi shakes his head. “The younger generations have an enormous awareness of environmental issues and are tech-driven.” The IAEA is leaning into this: it has recently taken the once unimaginable step of co-opting social media influencers — including the Brazilian model Isabelle Boemeke — to champion nuclear power.

Separately, Big Tech companies such as Microsoft, Elon Musk’s xAI and Sam Altman’s OpenAI are embracing the tech too, since they need vast supplies of electricity to power data centres. Renewable energy sources such as solar offer a cheap — fast expanding — option. But nuclear provides far more scale and reliability, albeit at much greater cost. “For the first time ever, we are seeing a [private sector] demand push, not just from governments and utilities,” notes Grossi, adding that one hallmark of the libertarian tech titans is that they want to break away from the communal grid. “They all want their own plants — their own!”

Grossi’s story about the Zaporizhzhia plant pops back into my mind — and I wonder if this embrace of civilian nuclear power is simply creating even more threats? At the 2019 COP, Grossi countered this by noting that the death toll from civilian nuclear accidents has hitherto been very small, even if you include Chernobyl. It is a powerful point: humans are bad at measuring risks and returns in a rational manner, and hitherto deaths from civilian nuclear use have indeed been negligible compared to those from the pandemic or climate change.

But Grossi also knows this logical — statistical — argument is not enough. So he is now planning another innovation: this year the IAEA will host its first dialogue with the biggest private-sector companies to discuss nuclear and AI. “Look at the Seven Sisters [for oil],” he says. “We want something like that.”

This sounds like a smart move, I reflect as I get the bill — not just to manage nuclear risks but to help Grossi’s UN bid. Would Trump support him for this role? “I hope so,” he replies. “I hope everyone does!”

But he knows, as do I, that any progress is extremely fragile. “Good luck!” I say, as we part, near the opera house. He walks away in the bright sunshine — and immediately checks his phones.

Gillian Tett is a columnist and member of the editorial board for the Financial Times

Find out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend on Instagram, Bluesky and X, and sign up to receive the FT Weekend newsletter every Saturday morning

Read the full article here