As magazine editor, author and political talk-show host, William F Buckley Jr is often called an intellectual godfather to the US hard right. Godfather, perhaps. Intellectual? Yes and no. He is remembered today less for his own ideas or for the big book on conservatism that he never wrote than for outstanding personal gifts. Buckley (1925-2008) had fierce verbal skills, charm that disarmed opponents and a talent for keeping disputatious intellectuals of the right together on the same magazine, National Review.

A sample of Buckley’s one-liners shows his pugilistic lightness and speed of attack: “I should sooner live in a society governed by the first 2,000 names in the Boston telephone directory than by the 2,000 faculty members of Harvard University” (1961); “Now listen, you queer. Stop calling me a crypto-Nazi or I’ll sock you in your goddamn face and you’ll stay plastered” (on network television, to fellow author Gore Vidal, 1968); “If Donald Trump were shaped a little differently, he would compete for Miss America” (2000). How little has changed over decades. Gender stereotypes and rival Harvard — Buckley was at Yale — were objects of hard-right scorn or mockery then, as now.

His flagship was National Review, which he founded in 1955 and ran until 1990. He held together its interventionist cold warriors, moral conservatives and economic libertarians, never insisting on consistency, which would have broken apart a more doctrinal magazine. On Firing Line — aired on public television — bien pensant liberals from easy backgrounds and good schools like Buckley’s often fell victim to his sly teasing and argumentative brio.

More strategic than dogmatic, Buckley’s contribution to restoring American conservatives’ self-confidence was managerial and polemical. He pressed them to sink their own conflicts by keeping liberals, not least liberal republicans, forever in view as a common enemy. The aim was not to shrink or cripple an activist federal state, inherited from Roosevelt’s New Deal and little challenged under the Republican presidency of Dwight Eisenhower, but to turn it to conservative ends.

In saying what those ends were, it mattered little to his success as a crusading publicist that Buckley stayed nimbly and systematically elusive. His conservatism was simple: it meant disagreeing with liberals. If that involved unprincipled-looking flux on, for example, big government, civil rights or Soviet détente, so be it. As Sam Tanenhaus writes in his massive and comprehensive biography, Buckley was always “best when on the attack”.

A former editor of the New York Times Book Review, Tanenhaus gives us Buckley, his career and his times in full, without idle praise or disapproval. The detail is meticulous, the feel for context assured and the ear ever open to a good story, which Buckley’s love of attention and disregard for the rules supplied in plenty. As the life of a quicksilver character in the round, it is unlikely to be bettered anytime soon.

Buckley’s father was an oilman with interests in Latin America and later offices in New York. He had big properties in Sharon, Connecticut, and Camden, South Carolina, where the family-owned local paper defended “massive resistance” to school desegregation. A traditionalist Catholic like his wife, Buckley Sr raised the family in the church and Buckley Jr remained Catholic, writing late-life reflections on his beliefs, mischievously titled Nearer, My God (1997).

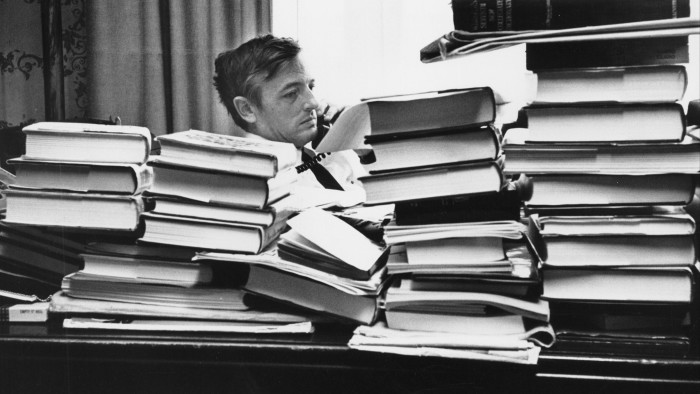

A middle child of 10, Buckley sought the limelight early. He cruelly mocked others but frequently made a fool of himself and laughed it off afterwards. He had, in Tanenhaus’s words, a genius for “intellectual comedy” but also a capacity to listen. He was engaging, cultivated, quick to make friends of all persuasions, musical, sporty (yachts and skiing), as well as a furious worker.

He never governed anything and ran for office only once, for mayor of New York as a Conservative in 1965, coming third with 13 per cent. Before that, in 1960, he had helped set up Young Americans for Freedom (YAF), a student countermovement on the right. His greater energies went on words — weekly journalism over six decades and some 50 books (including 15 political thrillers). His good friend, the liberal Harvard economist John Kenneth Galbraith, whom he wintered with in Gstaad, urged him to “write more, ski less”. Buckley ignored the advice. He never really started “The Revolt Against the Masses”, his magnum opus-to-be.

Buckley’s panache, social dexterity and openness to differences on his own side cannot hide that he was, by background and conviction, illiberal, tepidly democratic at best and for many years an outspoken racialist. Nor can his dandyish manner and scattershot output hide a career-long singleness of purpose: turning the Republicans into an illiberal, hard-right party.

Three books made him a name before he was 35. God and Man at Yale (1951) attacked his own university for taking money from rich and religious Republicans to teach their sons to be atheistic socialists. McCarthy and His Enemies (1954), written with his brother-in-law Brent Bozell, gently reproved Senator Joseph McCarthy, by then a discredited drunk, for “roughness” of method, while defending his rightness of cause: rooting out subversives in the US establishment. Up from Liberalism (1959) was vague on its proposed conservative replacement. Buckley was not promising to give conservatism more content but more edge and flare.

At National Review, he got rid of the Birchites — a conspiratorial fringe claiming Eisenhower for a communist — tamed the libertarians, dropped (eventually) the magazine’s white racism and sidelined its antisemites. Buckley did so less because he disagreed strongly with any of it than because pressing such views in seemingly consensual times distracted from turning Republicanism into an anti-liberal party. A goad or gadfly, not a party man, Buckley saw Eisenhower as a closet liberal and Goldwater as a saviour come too soon. He distrusted Nixonian “realpolitik” (though its champion Henry Kissinger became a good friend) and welcomed Reagan (who was wary of him), but died too soon to witness Trumpism and the final death of a liberal republicanism he had spent a career at war with.

Later campaigns in that same inner-party war are Quinn Slobodian’s focus in Hayek’s Bastards, where he tracks links between the 1940-50s free-marketry of Friedrich von Hayek and his followers and the 1980-90s early eruption of the rightwing populism with us now. Rather than a break within conservatism, Slobodian sees today’s hard right as a continuity.

He leads an expert tour through US hard-right think-tanks and magazines. His cast includes Ludwig von Mises, Murray Rothbard and Charles Murray, to cite better-known names. The dialectical give-and-take is not always easy to follow but the broad disputes he describes are familiar, unsettled and almost as old as conservatism itself. How to reconcile free-market libertarians with American nationalists and sociocultural moralists? How do conservatives in a democracy justify disbelief in equality?

Slobodian’s warring controversialists appear to have agreed at least on three points of political strategy. To replace communism and socialism, they chose as new enemies the state and its liberal defenders. Secondly, to justify belief in lasting inequality to present-day ears, the hard right turned to science or pseudoscience, with, for example, genetics and IQ testing. Lastly, with an eye on aggrieved (mainly white) working-class voters, the right concluded that it was not “the masses” but liberal elites who favoured egalitarian redistribution.

Buckley and Hayek’s Bastards look back but bear on today. Conservatives may wince to read that radicalism belongs in conservatism’s DNA. Liberals will probably find an old hunch confirmed: “new right” is a misnomer — the hard right was there to begin with.

Modern American conservatism was always a muddle of doctrines, interests and sentiments. Unmuddling them, on Buckley’s view, mattered less than mobilising them. Slobodian’s intellectuals doggedly fought each other for control of conservative ideas. Tanenhaus’s Buckley juggled them with shameless bravado. He was not, for that, a clown without consequence. Few did more to turn American public argument into ceaseless politico-cultural warfare between liberals and anti-liberals.

Buckley: The Life and the Revolution That Changed America by Sam Tanenhaus Random House $40, 1,040 pages

Hayek’s Bastards: The Neoliberal Roots of the Populist Right by Quinn Slobodian Allen Lane £25, 288 pages

Edmund Fawcett is the author of ‘Liberalism: The Life of an Idea’ and ‘Conservatism: The Fight for a Tradition’

Find out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend on Instagram, Bluesky and X, and sign up to receive the FT Weekend newsletter every Saturday morning

Read the full article here