Authored by Lance Roberts via RealInvestmentAdvice.com,

So Goes The First Five Days

Last week, we addressed the inability to sugarcoat the market’s poor performance heading into year-end. Furthermore, we discussed the “January Barometer,” which sets the year’s tone. To wit:

“However, even with a failed Santa rally, the January barometer holds the key for the year. Historically, a positive January has been a bullish sign for stocks. The chart below highlights that the popular Wall Street maxim has stood the test of time. Since 1950, the S&P 500 has posted an average annual return of 16.8% during years that included a positive January. Furthermore, the index generated positive returns in 89% of these years. In contrast, when the index traded lower in January, annual returns dropped to -1.7%, with only 50% of occurrences yielding positive results.”

However, before we reach the full month of January, the market must pass the first five days. As of Wednesday, which concluded the first five trading days of January, that market did generate a positive return, rising about 0.62%.

As we noted last week, this is the first of two “January Indicators” that have historically, on average, set the tone for the year. Since 1950, the S&P 500 has logged net gains during the first five days of the year 47 times. Of those 47 instances, the index ended the year up in 39 of them. That’s an 83% success rate for the first five-day theory. However, don’t get too excited. Of the 74 completed years since 1950, the S&P 500 has logged a full-year gain 73% of the time. That is likely because stocks are rising as the growth of the global economy continues despite the occasional stumble.

The last point is most notable, and most investors often ignore it. The first five days of January and the “January Barometer” are certainly statistically notable, but its failure rate as an indicator for bearish outcomes is also noteworthy. In the 27 years where stocks lost ground during the first five days of the new calendar year, the S&P 500 logged full-year gains in 15 of them anyway. In other words, the indicator only boasts a 45% success rate when predicting full-year losses.

It’s also worth noting that some of the market’s very best years since 1950 got started on a bearish foot. For example, the S&P 500 rallied 21% in 1991 despite losing 4.6% of its value during the first five days of that year. Conversely, despite rising 1.1% over the first five days of 2002, the S&P 500 lost more than 22% that year. When the theory is wrong, it can be very wrong.

As investors, these calendar-based time frames can give us some psychological comfort. However, the outcomes are likely not as closely tethered to reality as investors want to believe. As we discussed recently, the success rate as a bullish indicator is mainly rooted in that stocks rise more often than they fall.

Since 1900, the stock market has “averaged” an 8% annualized rate of return. However, this does NOT mean the market returns 8% every year. As we discussed recently, several key facts about markets should be understood. Stocks rise more often than they fall: Historically, the stock market increases about 73% of the time. The other 27% of the time, market corrections reverse the excesses of previous advances. The table below shows the dispersion of returns over time.”

In other words, while the first five trading days have been fruitful, investors should remain focused on the risks that could derail the markets further into the year.

This week, we will address the recent increase in volatility that has marked the beginning of the year.

Consolidation Continues

While Wall Street analysts continue to expect another bullish return year for stocks, December and January have been rather weak as markets consolidate the gains following the election. There are a few reasons for the recent bout of weakness. The first is that the markets were technically overbought heading into December and deviated above current moving averages. Such provides the conditions for a correction or consolidation, but a catalyst was needed.

That catalyst needed to be some event that changes the market’s perception about current valuations, expectations, or earnings. In this case, that catalyst occurred on December 18th when the Federal Reserve delivered a more “hawkish” FOMC meeting message that reduced the number of expected rate cuts in 2025. The perceived change in the Fed’s policy led to a jump in bond yields on the long end of the yield curve. Compounding that change in sentiment was stronger-than-expected economic data, which further supported concerns of inflationary pressures and reduced Fed policy changes.

The Federal Reserve’s modest shift in tone, when combined with an exuberant and overbought market, the ensuing consolidation should not have been unexpected. However, more bearish headlines have populated the media coverage recently, which happens whenever markets cease to rise. As of late, this has been the case, further increasing selling pressure in the markets. However, despite the rise in negativity, the market remains range-bound and holds above the 100-DMA moving average support. Furthermore, this consolidation over the last few weeks has fully reversed the overbought and deviated conditions.

That said, there are certainly reasons why this consolidation process could last longer. However, we are at levels more consistent with at least a short-term reflexive recovery. A good example is indicators like the percentage of stocks with bullish buy signals, which is at levels where stocks usually find some buying support.

Secondly, our technical gauge, comprising multiple weekly technical indicators from relative strength to momentum, has fallen to levels more consistent with short-term tradeable rallies.

In the near term, this weakness tends to beget more weakness. However, the “good news” is that such low readings have often marked the bottom of market corrections and consolidations.

Technically, nothing is “wrong” with the markets, and the overall bullish trend remains. The consolidation process will likely pass, and more constructive price action will take hold. However, investors should always “err to the side of caution” and understand that there are times when a consolidation process can turn into a more significant correction.

How will we know the difference?

Technical Breakdown Levels To Watch

As we will discuss next, some issues could derail the more bullish expectations for 2025. However, one of the investors’ most significant mistakes is tied to the psychological bias of “loss aversion.”

What is loss aversion?

“Loss aversion is a tendency in behavioral finance where investors are so fearful of losses that they focus on trying to avoid a loss more so than on making gains. The more one experiences losses, the more likely they are to become prone to loss aversion. Research on loss aversion shows that investors feel the pain of a loss more than twice as strongly as they feel the enjoyment of making a profit.” – Corporate Finance Institute

According to CFI, examples of “loss aversion” include:

- Investing in low-return, guaranteed investments over more promising investments.

- Not selling a stock when your current rational analysis of the stock indicates that it should be.

- Selling a stock that has gone up in price to realize a gain of any amount, even though analysis indicates investors should hold the stock.

- Telling oneself that an investment is not a loss because the sell transaction has not occurred.

Even more notable is that many investors avoid bull markets, expecting the eventual bear market decline to wipe them out. These are all emotional decisions driven by either actual or expected price declines.

However, bear markets rarely happen all at once. In most bear markets, the market showed plenty of warning signs well before the “bear” came out of hibernation. Such gave investors ample time to exit the market, reduce risks, and raise cash to minimize the eventual reversion to capital. Currently, there are warning signs we should be paying close attention to.

For example, the number of stocks in long-term uptrends continues to dwindle, as noted by Sentimentrader.com this week:

“The latest indicator highlighting the dwindling participation comes from the percentage of stocks in the S&P 500 trading above their 200-day average. For only the 8th time since 1928, fewer than 52% of the members held above their long-term averages as the S&P 500 resided within 3% of a high. As shown in the chart below, when fewer than 52% of stocks are above their 200-day average or fewer than 57% exhibit a rising 200-day average, annualized S&P 500 returns decline to 4.2% and 5.2%, respectively, well below the returns seen above these levels.“

Secondly, credit spreads suggest that market risk is well elevated. Credit spreads have NOT yet signaled market stress; however, they tend to be a strong leading indicator of bearish market downturns. The investment-grade bond to AAA spread is near its lowest level. The vertical bars denote when that spread increased, and markets generally suffered downturns either coincidentally or lagged by some period.

Furthermore, we can look at the spread between the 10-year US Treasury and “junk bonds.” As the chart shows, when this spread is at very low levels, as it is currently, and rises, the market eventually undergoes a corrective process.

While watching participation and credit spreads certainly warns investors to reduce portfolio risk, the market will also provide clues. There are several important support levels that, if broken, will bring increasing selling pressure into the market. The first level sits at 5870. If that level fails, prices will search for support near 5619, coinciding with the July 2024 peak just before the “Yen Carry Trade” event. If the market reaches that level, it will likely be oversold enough to provide investors with a counter rally to reduce risk further.

However, if the market rallies and fails, the next support levels become more critical. 5400 and 4971 are going to start breaching levels that will trigger further algorithmic selling and could lead to a more aggressive selloff. Investors should be fully risk-reduced if the market starts breaching these levels. A corrective move would likely encompass a 25% decline from peak to trough.

While such a decline should be expected at some point, there is no guarantee that a significant correction will happen this year or even next. An event or catalyst is needed to reverse the market’s earnings expectations to cause a reversal in market valuations. Given currently elevated valuations, such an event could lead to a significant price realignment. Therefore, watching breadth and credit spreads will indicate whether a current consolidation is just a consolidation or the beginning of a larger corrective process.

Speaking of risks to the markets and valuations. Another issue on our radar is worth discussing.

Yields And Equity Risk Premiums

Over the past few weeks, two entirely “sentiment-driven“ things have plagued the markets: concerns that “tariffs” could lead to inflationary pressures and valuations. The concern over tariffs has created a feedback loop in the economy. Since the election, producers have been buying products to get ahead of tariffs, which increased demand for those products, pushing prices higher, as seen in recent ISM reports. In other words, the fear of tariffs creating inflation caused inflation by their actions. However, as discussed in this article, tariffs haven’t caused inflation historically.

That “sentiment shift” on inflationary pressures has caused bond yields to rise as hedge funds and portfolio managers shift positioning rather than reflecting underlying fundamentals. As Michael Lebowitz noted this week:

We created a relatively simple but highly effective proprietary fundamental yield model based on inflation and economic growth. Our bond yield model only uses two inputs.

- Inflation—The Cleveland Fed Inflation Expectations Model. This model is unique as it uses actual inflation data and market—and survey-based measures of inflation expectations. The combination of actual and expected price changes provides a complete inflation picture.

- Economic activity– Real GDP. Real GDP strips out inflation to estimate economic activity without the impact of price changes.

We then ran a multiple regression analysis of the two inputs with yields. Doing so created a significant correlation with an r-squared of .9702.The line graph comparing the expected model yield to actual yields shows that the model yield is 3.78% versus the actual yield of 4.57%. The difference of .79% is the term premium.

In other words, the recent yield run has little to do with the economic fundamentals and more with sentiment. Therefore, as the economic fundamentals take hold and inflation continues to decline towards the Fed’s target of 2%, the excess premium will eventually be reversed from the market. As Michael concludes:

“So why are bond yields rising? During the fourth quarter, the ten-year UST yield rose by 62 basis points. 52 basis points were due to the rising term premium, leaving only 10 basis points as the result of economic activity and inflation. The two culprits behind the jump in the term premium were the fear of deficits and inflation. Even with no change to the fundamental factors, a sizeable return can be had in longer-term bonds if the premium diminishes. Furthermore, those returns could be supercharged if a recession, economic weakness, and/or a return to 2% or less inflation occurs.

Bond investors will most likely be rewarded handsomely when economic fundamentals normalize and the term premium fades. Until then, sentiment, not economic data, is the key factor impacting rates.”

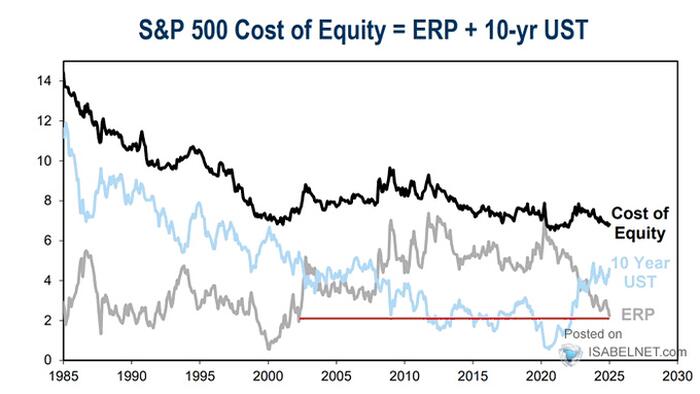

Secondly, valuations are becoming more of a concern for markets, particularly as the equity risk premium declines. Equity risk premiums (ERP) are also driven by sentiment. As investors expect increased asset prices, they are willing to be “paid less” for the “risk” they are taking to own equities. However, with bond yields now significantly above the ERP, there is an increasing probability that investors, at some point, may opt for being “paid” by owning bonds.

The stock and bond markets are currently detached from the underlying fundamentals. If, or rather when, a reversion takes hold, the decline in equity risk will be offset by the rise in bond prices as yields realign with economic fundamentals. This has been the case, particularly when rates rise significantly into an overvalued market.

There is little reason to expect this time to be any different.

Loading…

Read the full article here