U.S. automakers are quietly pivoting back toward what they know makes money: large gasoline vehicles. Selling trucks and SUVs is now the fastest path to higher profits, especially as government pressure to push electric vehicles has weakened. Trying to maximize profits from gas cars while keeping pace in EV technology is proving extremely difficult, according to a new writeup from the Wall Street Journal.

Recent policy changes strongly favor gasoline models. Fuel-economy rules have been softened, penalties for missing targets have disappeared, EV tax credits have expired, and California can no longer impose its own emissions standards. EV momentum has cooled worldwide as well, with Europe, the U.K., and Canada also retreating from aggressive mandates. BloombergNEF projects U.S. EV sales will drop 24% in Q4 2025 from the year before.

Automakers are responding quickly. GM, Ford, and Stellantis have announced plans to emphasize gasoline vehicles, which deliver far better margins. Thousands of EV-factory jobs have been cut and several plants paused. As RBC’s Tom Narayan explains, “Even one quarter of mismatched production can result in billions of dollars of losses.”

Their caution is understandable. EV programs have been deeply unprofitable. Ford alone lost nearly $13 billion on EVs between 2021 and 2024, and now expects $19.5 billion in new charges, largely EV-related. Meanwhile, easing regulations are creating what Ford CEO Jim Farley calls a “multibillion-dollar opportunity over the next two years.” TD Cowen estimates profit gains of $4B for Ford, $3B for GM, and €1.4B for Stellantis from these regulatory shifts.

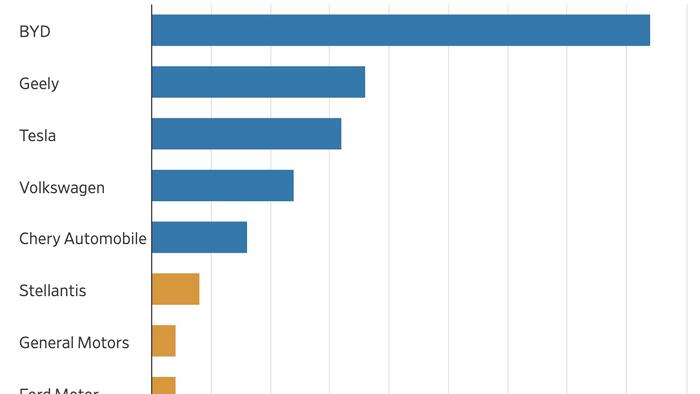

Publicly, the companies still claim commitment to EVs. GM CEO Mary Barra says “profitable electric-vehicle production” remains the firm’s goal, and Farley warns that Chinese rivals like BYD and Geely are the real competition. But reality is sobering: the Detroit Three together control less than 5% of global EV sales, while BYD, Geely, and Tesla hold nearly 40%.

WSJ writes that part of the problem is demand. Consumers have resisted expensive electric versions of large vehicles that don’t suit long-distance or commercial use. Ford now plans a smaller, cheaper electric pickup around $30,000 for 2027. GM is redesigning EVs to be lighter and more aerodynamic. Both companies are also trying to keep flexibility by producing EVs and gasoline cars in the same plants. As Barra put it, “we have the ability to flex back and forth between ICE and EVs.”

That flexibility, however, undermines efficiency. BloombergNEF’s Colin McKerracher argues that scale is essential for lowering battery costs, and John Murphy of Haig Partners notes that mixed production lines inevitably sacrifice efficiency.

Believing Detroit can dominate EVs now requires faith: that low-cost EVs can be built without massive scale, that U.S. firms can match the speed of Chinese rivals who release new models every 1.8 years versus 5.2 years for Western firms, and that Chinese automakers will stay out of the U.S. market indefinitely.

There is another path. Like U.S. oil companies that ignored renewables and doubled down on their most profitable business—with strong results—the Detroit automakers could lean into gasoline and hybrids. Hybrid demand is still growing and uses nearly the same supply chain as traditional vehicles. S&P Global Mobility expects global gasoline and hybrid sales to rise through at least 2032.

The danger is timing. The world could transition to EVs faster than expected, leaving U.S. automakers stuck behind. For now, though, profits from gas vehicles are simply too attractive to resist.

Loading recommendations…

Read the full article here