Submitted by Brent Johnson of Macro Alchemist (read it here in pdf format)

The transformation of banking and financial services away from traditional public markets and the banking system itself has been dramatic since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2008.

This shift has reshaped the financial landscape, as more activities that were once dominated by banks and public markets have moved into private and non-bank financial sectors.

In 2008, when the GFC struck, the financial world experienced a severe breakdown. Banks, which had been the backbone of lending and liquidity, stopped trusting one another, ceasing to lend in overnight markets, which are crucial for short-term liquidity. Simultaneously, public markets suffered immense losses, with the S&P 500 plunging by roughly 50%.

As a result, both the banking system and public markets effectively froze, becoming illiquid and dysfunctional almost overnight. What had once been highly liquid, smoothly functioning financial ecosystems ground to a halt.

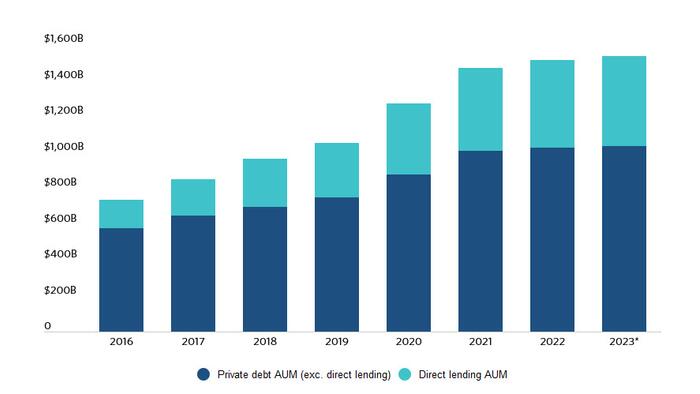

Fast forward to today, and we are witnessing a striking evolution: the non-bank financial sector, which includes institutions like hedge funds, private equity firms, and shadow banks, has grown larger than the traditional banking sector. Similarly, private markets, such as those for private equity, private debt, and direct lending, are expanding at a much faster rate than public markets.

This rapid growth is fundamentally altering the structure of global finance.

Such a shift of this magnitude raises critical questions about the potential impact on future financial crises. One key issue is that risk-taking is now concentrated in markets that are inherently less liquid. Even before a liquidity crisis occurs, the financial system is building up risk in markets that, by their nature, are harder to exit quickly. So, what happens when these already illiquid markets face a shock and become even less liquid, potentially triggering a crisis?

Consider direct lending, private credit, and private equity investments, all of which are largely concentrated in the non-bank financial sector. If the global financial system could experience a crisis of the scale seen in 2008—when liquidity dried up in highly liquid public markets—what might happen when the starting point for risk-taking is in far less liquid, private markets?

The consequences could be even more severe and far-reaching.

This paper explores the rapid expansion of the non-bank financial sector and the liquidity constraints that characterize private markets.

One of the key concerns with liquidity crises is the cascading, second- and third-order effects they can generate. These effects occur when markets that are perceived to be liquid—markets where investors believe they can easily buy and sell assets—suddenly become illiquid, trapping participants and causing widespread disruptions.

Such second and third order effects often impact investors, institutions, and sectors that would ordinarily consider themselves insulated from high-risk financial activities.

However, the interconnectedness of the global financial ecosystem means that shocks in one part of the system can quickly reverberate through others, catching seemingly unrelated players in the fallout. This is why understanding shadow banking, private markets, and the broader non-bank financial system is critical for assessing the risks posed to the overall financial system.

The increasing prominence of non-bank and private financial markets presents new challenges for managing liquidity and systemic risk. As the financial system becomes more dependent on these less liquid sectors, the potential for liquidity crises and their ripple effects across the global economy grows, highlighting the importance of monitoring and addressing risks in the shadow banking and private market ecosystems.

Backdrop – The Global Financial Crisis

No two financial crises are exactly the same, though human behavior and emotions are always central to them. Each crisis has its own unique characteristics, and as long as human nature remains constant, cycles of boom and bust are inevitable.

Given today’s historically high equity valuations, comparisons to the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2008 and the Dot-Com bubble of the late 1990s are natural, and the current enthusiasm for Artificial Intelligence is reminiscent of past periods of euphoria. However, it’s important to remember that valuations are symptoms of broader market conditions, not the underlying causes. For example, during the Dutch Tulip Mania in 1636, a single black tulip was valued at several years’ salary—an indicator that something was amiss, but not the root of the issue.

Pinpointing the exact moment when a financial crisis begins is often only possible in hindsight. Did the GFC start with the collapse of two Bear Stearns hedge funds in 2007? Was it the fall of Bear Stearns itself? Or perhaps Lehman Brothers’ collapse? Some might even argue it began with Meredith Whitney’s 2008 analysis, revealing that Citigroup couldn’t maintain its dividend. The answer depends on perspective—those directly impacted by these events would likely give different timelines.

What’s crucial today is understanding that comparing current credit conditions to 2008 is misleading.

All credit crises share a common feature: relaxed lending standards. Before the GFC, subprime lending accounted for around 3% of mortgage lending; by 2007, it had surged to nearly 25%. Loan standards deteriorated so badly that defaults on the first mortgage payment were rising, yet this was just one part of the problem.

Other key players in the crisis were institutions like Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and the mortgage insurer MBIA. As long as these entities retained their high credit ratings, they were able to keep issuing loans to borrowers who couldn’t repay. MBIA, for example, wrote billions in liabilities while holding only $30 million in shareholder funds.

But the real breaking point came when large banks stopped lending to each other overnight, driven by concerns about both their counterparts’ liquidity and their own over-leveraged balance sheets. Bear Stearns, for instance, had $3 of equity for every $100 in assets, a precarious 33:1 leverage ratio.

Once regulators stepped in after the crisis, they sought to prevent a repeat by imposing stricter rules on large banks through the Dodd-Frank Act. This curtailed trading and market-making activities, bringing these financial giants into line. But as with any financial system, where there is demand, supply will find a way. This time, the non-bank financial intermediaries (NBFIs) stepped in. In just over a decade, these NBFIs grew to become the largest lenders, overtaking traditional banks.

The lesson here is simple: credit demand doesn’t disappear—it shifts. Understanding where that demand goes is crucial in predicting how future financial risks may unfold.

The Rapid Growth of Non-Bank Financial Institutions (NBFI)

In addition to the increased regulatory pressure on banks after the 2008 crisis, the prolonged low-interest-rate environment has been a major catalyst for the rapid growth of non-bank financial institutions (NBFIs).

With traditional savings accounts and government bonds offering historically low yields, investors began seeking higher returns through alternative avenues. NBFIs responded by offering a range of financial products that provided more attractive returns, such as collateralized loan obligations (CLOs), private debt, real estate investment trusts (REITs), and other investment opportunities that banks, due to regulatory constraints, did not provide.

This shift allowed NBFIs to fill a crucial gap in the market by catering to the increasing demand for yield-driven investment products.

As banks became more restricted in their ability to engage in riskier, high-yield activities due to post-crisis regulations like the Dodd-Frank Act, NBFIs stepped in with offerings that were not only higher-yielding but also often more complex and less transparent. The flexibility of NBFIs to operate with fewer regulatory barriers became an attractive alternative for both institutional and retail investors hungry for returns in a low-rate world.

At the same time, technological innovation has accelerated the growth of NBFIs, especially through the rise of fintech companies. These firms have revolutionized the financial services sector by utilizing data analytics, artificial intelligence, blockchain, and digital platforms to deliver more efficient and accessible financial solutions.

Fintech innovations such as peer-to-peer lending platforms, robo-advisors, online wealth management services, and digital payment systems have disrupted the traditional banking model. These technologies offer faster, more cost-effective services tailored to the modern consumer, enabling individuals and businesses to access credit, make investments, and manage their finances without relying on traditional banks. Fintech’s rise has made NBFIs even more prominent by providing an infrastructure that is more agile and responsive to market demands.

However, with this agility comes a trade-off in oversight.

Because NBFIs are subject to fewer regulatory constraints than traditional banks, they can accumulate risks that may not be visible to regulators or market participants until it’s too late. Hedge funds, for example, often engage in highly leveraged strategies, which can magnify losses during periods of market volatility. The collapse of such funds can quickly spiral into broader financial instability, as these firms are tightly interconnected with traditional banks and financial institutions through various channels of lending, derivatives, and investment portfolios.

An example of this occurred in 2020, during the market turbulence triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic. Money market funds, once considered stable and low-risk investments, experienced rapid outflows as investors fled to safety, highlighting the unpredictable fragility within certain corners of the NBFI sector.

The spillover effects of these outflows flowed throughout the broader financial system, underscoring the interconnected nature of banks and NBFIs.

Given the systemic importance of NBFIs, policymakers and regulatory bodies, including the Federal Reserve and the Financial Stability Board (FSB), have become increasingly concerned about the potential risks posed by the growing influence of these institutions. There is ongoing debate about whether NBFIs should be subject to the same level of scrutiny and oversight as traditional banks, particularly those that have grown large enough to pose a significant threat to financial stability.

The challenge for regulators is to strike a balance between encouraging the innovation and growth that NBFIs bring to the financial system, while ensuring that these institutions do not become the next source of systemic risk.

However, history suggests that regulators are often reactive rather than proactive when it comes to addressing potential crises. Despite growing awareness of the risks associated with NBFIs, regulatory intervention may lag until after significant financial disruptions have already occurred.

The rise of NBFIs represents a profound shift in the U.S. financial system. Their ability to innovate rapidly, operate with less regulatory oversight, and meet investor demand for higher-yielding products has allowed them to outpace the traditional banking sector in many respects. Yet, their growth also requires a closer examination of their role in maintaining financial stability.

The lack of visibility into NBFIs’ balance sheets and activities poses a risk, as it makes it harder to assess their vulnerabilities and potential for triggering broader financial distress. As NBFIs continue to expand, understanding their impact on the overall financial ecosystem will be crucial in preparing for and mitigating the risks of future financial crises.

Private Equity and Credit Markets

Private equity and private lending have not only expanded in size but also grown in complexity, becoming critical pillars of global finance.

These sectors have evolved in response to regulatory changes, technological advancements, and shifting investor demand, reflecting broader trends across the financial landscape.

Initially, private equity was a niche field focused on venture capital for early-stage companies and distressed assets. It played a limited role in mainstream corporate finance. Over time, however, private equity has matured into a sophisticated industry that now employs a wide range of investment strategies, including leveraged buyouts (LBOs), growth equity, special situations, distressed investing, and infrastructure investments.

Leveraged buyouts (LBOs), in particular, have become a defining feature of private equity. These transactions allow firms to acquire companies using a mix of equity and significant amounts of borrowed capital, with the expectation that the target company’s cash flow will be used to pay off the debt.

The rise of LBOs has transformed how private equity firms approach value creation, using financial leverage to amplify returns while taking control of large, established companies. This strategy has proven immensely profitable, but it also introduces higher levels of risk, particularly in uncertain economic environments.

In recent years, private equity firms have shifted from purely financial strategies, like cost-cutting and restructuring, to a more hands-on operational approach. Known as the “operational value-add” strategy, private equity firms now leverage their industry expertise and resources to drive operational improvements, digital transformation, and leadership development within their portfolio companies.

By engaging more actively in business operations, private equity firms are unlocking new growth opportunities and generating more sustainable returns, setting themselves apart from traditional investors.

Furthermore, private equity firms are increasingly investing in technology-driven sectors, such as software, fintech, healthcare technology, and digital infrastructure.

The rise of tech-focused private equity funds reflects the industry’s growing recognition that innovation and data analytics are key to staying competitive in the modern economy.

By adopting data-driven decision-making and enhancing due diligence processes, private equity firms are now better positioned to identify high-potential investments and maximize long-term growth.

At the same time, private lending has grown into a critical component of alternative finance, providing capital to companies that may not qualify for traditional bank loans. The sector’s rapid expansion is a direct response to the regulatory tightening following the 2008 financial crisis, which limited banks’ ability to engage in riskier lending activities.

Direct lenders—including private credit funds, hedge funds, business development companies (BDCs), and institutional investors—offer a diverse array of debt instruments, such as senior secured loans, uni-tranche loans, mezzanine financing, bridge loans, and subordinated debt. Private lenders’ flexibility and speed in underwriting and approving loans have made them an appealing option for companies looking to finance leveraged buyouts, acquisitions, expansions, or debt refinancing. Their ability to offer more customized terms than traditional banks has enabled private lending to become a significant source of financing, particularly for middle-market companies.

The rise of private lending has also been fueled by the global search for yield in a low-interest-rate environment.

Institutional investors, including pension funds, insurance companies, and endowments, have increasingly allocated capital to private debt as it offers attractive risk-adjusted returns with low correlation to traditional equity and fixed-income markets.

This influx of capital has allowed private lending firms to scale their operations, even competing with traditional banks on larger, more complex transactions.

Technological innovation has also played a transformative role in both private equity and private lending.

In private equity, advancements in data analytics, artificial intelligence, and machine learning have revolutionized deal sourcing, due diligence, and portfolio management. Firms now use sophisticated tools to assess market trends, predict business performance, and identify high-potential investment opportunities.

Similarly, in private lending, the rise of digital platforms and marketplace lending has democratized access to credit, allowing businesses to secure loans through online platforms that connect borrowers directly with investors.

This innovation has streamlined the lending process, reduced costs, and increased transparency.

Due to their significant growth, private equity and private lending are facing increased scrutiny from regulators due to concerns over high levels of leverage, lack of transparency, and the potential buildup of systemic risks.

In private equity, the use of leveraged buyouts has raised questions about the impact of high debt levels on the financial stability of acquired companies, especially during economic downturns. Additionally, private equity’s impact on employment and wages has drawn criticism, with some arguing that short-term profit motives can undermine long-term business sustainability.

In private lending, the rapid expansion of direct lending and private credit funds has triggered concerns about the buildup of credit risks outside the traditional banking system. Since private lenders operate with far fewer regulatory constraints, there is less visibility into their risk exposures.

As these institutions continue to grow and become more interconnected with traditional banks and other financial institutions, distress in the private lending market could have far-reaching implications for the broader financial system.

The broader Non-Bank Financial Intermediaries sector, of which private equity and private lending are key components, has seen explosive growth since the 2008 financial crisis.

With the NBFI sector now being larger than the traditional banking system in the U.S., its growth trajectory still shows no signs of slowing down.

This rapid expansion has caught the attention of regulators such as the Financial Stability Board, who are increasingly concerned about the systemic risks posed by the shadow banking sector. Historically, tighter regulatory frameworks—like the Dodd-Frank Act—have only been enacted in response to crises, such as the 2008 meltdown, when it became clear that greater oversight was needed.

Their rapid growth and evolving complexity present both opportunities and challenges.

While these sectors have provided new avenues for investment and credit, their lack of transparency and regulatory oversight makes them vulnerable to systemic risks.

The FSB acknowledges the need for tighter regulatory frameworks to mitigate these risks, but historically, such regulations tend to be reactive, implemented only after a crisis occurs.

Legislation such as Dodd-Frank would not have been necessary had the Clinton Administration not repealed the Glass-Steagall Act in the 1990s—a law originally enacted in the aftermath of the 1929 stock market crash to regulate the banking industry. The repeal removed the separation between commercial and investment banking, a move that many argue contributed to the excesses leading up to the GFC.

Today, the NBFI sector has become an increasingly important borrower, which carries two significant implications.

First, the line between traditional banks and non-bank financial institutions has become increasingly blurred, even though they operate under different regulatory regimes. This blurring creates ambiguity around risk oversight.

Second, NBFIs are borrowing at a much faster rate than the overall market, raising concerns that the sector could be headed for a crisis of its own.

The question remains: will regulators act in time, or will they once again be left playing catch-up when growth rates like these become unsustainable?

Moreover, private equity firms and direct lenders have become vital sources of credit for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and leveraged buyouts. These areas are often considered too risky or capital-intensive for traditional banks, further underscoring the growing role that NBFIs play in providing essential credit where banks have become more risk-averse.

As NBFIs continue to expand in influence and borrowing magnitude, the urgency for regulatory bodies to address their systemic risks grows—before another financial crisis emerges from the shadows.

Shadow Banks and Private Markets – Illiquidity

Liquidity risk is one of the most significant challenges faced by private equity and private lending firms, largely shaped by the illiquid nature of their investments, market dynamics, and their funding structures.

These firms invest primarily in assets without active secondary markets, making it difficult to quickly convert investments into cash. While taking on illiquidity risk allows them to pursue higher returns, it also exposes them to considerable vulnerabilities, especially during times of financial stress or economic downturns.

In private equity, firms acquire stakes in privately held companies or engage in leveraged buyouts (LBOs) of public companies. These investments typically involve multi-year commitments, with the goal of enhancing operations, growing value, and eventually exiting via a sale or initial public offering (IPO).

However, when markets enter downturns, the exit strategies of private equity firms often face severe constraints.

In such situations, potential buyers may vanish, and IPO markets may close, leaving firms unable to sell their holdings at favorable prices—or in some cases, unable to sell at all. This lack of liquidity creates significant challenges, tying up capital much longer than expected and potentially derailing planned investment cycles. Without the ability to exit their investments, private equity firms can experience a liquidity crunch, where the inability to generate cash flow limits their ability to return capital to investors, pursue new investments, or meet other financial obligations.

Similarly, private lending firms face their own liquidity risks.

These firms provide loans to businesses that often fall outside traditional banking channels, including middle-market companies and those with lower credit ratings. While these loans typically offer higher yields to compensate for the greater risk, they come with a major trade-off: illiquidity. Unlike publicly traded bonds, which can be quickly bought and sold on secondary markets, private loans lack a ready market, making it difficult for lenders to raise cash in times of need.

During periods of financial distress, these risks become even more pronounced. Companies facing economic challenges may struggle to meet their repayment schedules or refinance their debt, leading to a higher rate of defaults. As defaults rise, the value of these private loans can plummet, leaving lenders exposed to significant losses. The inability to sell or restructure these illiquid loans in a timely manner compounds the liquidity risk, as lenders face mounting pressure to meet their own financial commitments.

Moreover, the increasing use of payment-in-kind (PIK) structures, where interest payments are capitalized rather than paid in cash, adds another layer of complexity.

While PIK arrangements provide temporary relief to borrowers by postponing cash payments, they heighten liquidity risks for lenders. Capitalizing interest rather than receiving cash inflows delays revenue and pushes the lenders deeper into illiquid positions, further limiting their ability to generate liquidity when needed. In times of economic stress, this can leave lenders with growing obligations but limited options for raising cash, intensifying financial vulnerabilities across the system.

Of course, a key factor that exacerbates liquidity risk in both private equity and private lending is the use of leverage.

Private equity firms often rely heavily on debt to finance acquisitions, using the acquired company’s cash flow to service that debt. When cash flows falter or interest rates rise, debt servicing becomes more difficult, potentially forcing firms to inject more capital into struggling companies or sell assets at a steep discount.

In private lending, leverage is present both in the loan structure and in borrowing companies. If economic conditions worsen, highly leveraged borrowers may struggle to repay their loans, leading to defaults and creating further liquidity pressure for lenders who depend on regular repayments to maintain their own financial commitments.

Another dimension of liquidity risk comes from the fund structure itself.

Private equity and credit funds are typically closed-end, meaning investors cannot access daily liquidity like in mutual funds or ETFs. Investors commit capital for a set period, usually 5 to 10 years, expecting distributions from asset sales over time.

However, if too many investors demand early liquidity, these funds may be forced to liquidate assets under unfavorable conditions, creating what is known as a liquidity mismatch. This problem is often magnified during economic crises, when many investors seek to withdraw funds simultaneously, putting additional pressure on these funds to generate liquidity when they are least able to.

The COVID-19 pandemic provided a recent example of this liquidity mismatch. During the market turmoil, many investors sought to reduce their exposure to riskier assets, prompting significant pressure on private equity and credit funds to meet these demands in a difficult market. If forced into fire sales, these funds can push asset prices lower, sparking a downward spiral that further erodes investor confidence and increases redemption requests.

Private equity and lending firms also rely on external financing from banks or other financial institutions to manage liquidity needs and execute deals. This reliance further entangles these firms with traditional banks and non-bank financial intermediaries (NBFIs), despite operating under different regulatory frameworks. In times of economic stress, banks may tighten lending conditions or withdraw credit, adding more complexity to liquidity management for these firms.

The interconnectedness of the financial markets means that liquidity issues within private equity and lending firms can have broader implications for the entire financial system. As these sectors have grown, they have become deeply intertwined with banks, institutional investors, and other market participants. A liquidity crisis in one area can trigger wider disruptions, affecting asset prices, credit availability, and investor sentiment across the financial ecosystem.

For the broader NBFI sector, managing liquidity risk is critical, as it directly impacts their operational stability and ability to navigate financial stress. NBFIs, which include entities such as asset managers, hedge funds, insurance companies, private equity firms, and private credit funds, provide crucial financial services without the same access to central bank liquidity or deposit bases that traditional banks rely on.

This lack of access makes liquidity management more challenging for NBFIs, particularly because they often hold or finance illiquid assets such as private debt, real estate, or equity stakes in private companies. During periods of volatility, these assets become even more difficult to liquidate, exposing NBFIs to significant liquidity risk if they need to meet sudden cash demands.

Many NBFIs face an additional challenge from their reliance on short-term funding to finance longer-term investments. This funding mismatch, where liabilities are short-term and assets are long-term, leaves NBFIs vulnerable when short-term funding markets tighten or become more expensive.

For instance, hedge funds and private credit funds often depend on short-term repurchase agreements (repos) or commercial paper to finance their positions. If these markets dry up during periods of stress, NBFIs can face severe liquidity pressures that threaten their solvency.

Investor runs or mass redemption requests are another prominent liquidity risk for NBFIs. Investment funds, such as mutual funds, ETFs, and hedge funds, allow investors to redeem their investments on short notice. In times of uncertainty, a rush of investors trying to withdraw their money can force NBFIs to sell assets quickly at depressed prices, further exacerbating market stress and undermining investor confidence.

Given the interconnectedness of NBFIs with the broader financial system, liquidity challenges can have far-reaching effects. Many NBFIs maintain relationships with banks and other institutions through credit lines, derivatives, and other financial instruments.

If an NBFI experiences a liquidity crisis, the impact can quickly spread to other market participants, affecting asset prices and destabilizing the broader financial system.

The growing systemic importance of NBFIs highlights the need to carefully manage liquidity risk within this sector. As these institutions continue to take on roles traditionally filled by banks, the potential for liquidity pressures to create broader market disruptions has increased.

While NBFIs provide essential credit and financial services, their reliance on illiquid assets and short-term funding leaves them particularly vulnerable to market shocks, making liquidity risk a central concern for the stability of the financial system.

Conclusion

The transformation of the global financial landscape since the 2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC) has been monumental.

The shift from traditional banking systems and public markets toward non-bank financial intermediaries (NBFIs) and private markets has significantly altered the structure and functioning of finance. As a result, NBFIs—including hedge funds, private equity firms, private credit funds, and fintech companies—have grown to occupy a larger portion of the financial ecosystem, becoming major players in corporate lending, investment management, and liquidity provision.

One of the most profound developments has been the rapid expansion of private equity and private lending markets. These sectors have evolved to meet investor demand for higher-yielding opportunities, offering a wide range of innovative financial products such as leveraged buyouts (LBOs), private credit, and alternative debt structures. The rise of these markets is a testament to the adaptability of finance and the relentless pursuit of returns. However, it is not without significant risk—particularly in the realm of liquidity.

Liquidity risk remains a critical challenge for private equity and private lending firms. Both industries rely on illiquid assets, such as private debt and equity stakes, which are difficult to convert into cash when needed.

This inherent illiquidity can become a major vulnerability during periods of financial stress, when market conditions deteriorate, exit strategies are delayed, and asset sales become constrained. The complex and often opaque nature of these investments further compounds the risk, making it difficult for market participants and regulators to accurately assess the extent of exposure.

The use of leverage amplifies these risks.

Private equity firms, in particular, utilize significant amounts of debt to finance acquisitions, while private lenders provide loans to highly leveraged borrowers. When economic conditions worsen, the strain on both the firms and their borrowers becomes acute, leading to increased defaults, liquidity shortages, and the potential for forced asset sales. This situation is exacerbated by the “payment-in-kind” (PIK) structures that delay cash flow, creating additional stress on firms’ liquidity positions.

Another crucial aspect of liquidity risk lies in the fund structures used by private equity and private credit firms. Closed-end funds with limited liquidity options can face a liquidity mismatch during economic downturns, as seen during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Investors, seeking to withdraw capital, may force these funds to sell assets at unfavorable prices, sparking further market disruption. Moreover, the reliance of private equity and lending firms on external financing from traditional banks ties them closely to the regulated financial system, despite operating under different regulatory frameworks.

As private equity, private lending, and NBFIs continue to grow in influence, so too does their interconnectedness with the broader financial system.

This interconnectedness poses systemic risks.

A liquidity crisis within one sector could quickly cascade across the financial landscape, leading to broader disruptions in asset prices, credit availability, and investor sentiment. The ripple effects of a crisis in private markets or shadow banking could undermine the stability of the global economy, just as the collapse of major financial institutions did during the 2008 GFC – but with less warning due to less visibility.

The starting point for private markets is illiquidity, unlike public markets whose starting point is liquidity. When things get illiquid, and they always do, this will pose a much bigger problem for private markets.

Despite the significant role NBFIs play in modern finance, the regulatory framework governing these institutions lags behind their growing importance. NBFIs operate with far less oversight than traditional banks, which heightens the risks associated with leverage and illiquidity.

While the lessons from past crises, such as the GFC, have led to some regulatory improvements, history shows that regulations often follow crises rather than prevent them.

The question remains whether policymakers can enact tighter oversight of the NBFI sector before a liquidity-driven crisis emerges.

In conclusion, the rise of NBFIs and private markets presents both opportunities and challenges.

While these sectors have provided new avenues for investment and credit, their inherent illiquidity and use of leverage make them vulnerable to market shocks. The growing systemic importance of NBFIs highlights the need for a proactive regulatory approach to managing liquidity risks.

Only by addressing these vulnerabilities can the financial system hope to mitigate the impact of future crises, ensuring that the benefits of financial innovation do not come at the cost of systemic stability.

About

The Macro Alchemist is an amalgamation of ideas, experiences, and investing disciplines sourced over decades from the minds of Brent Johnson and Michael Peregrine.

Explore this latest topic further, and additional market insights from the creators, at MacroAlchemist.com

Loading…

Read the full article here