In hangar number five at BAE Systems’ sprawling factory in north-west England, test pilots are putting the world’s most advanced fighter jet through its paces. The pilots have already flown more than 170 hours over 125 outings but the jet itself has not yet been built; the flights have taken place inside a bespoke simulator in the cavernous space.

The virtual testing will help to inform live trials of a supersonic prototype aircraft scheduled to fly in 2027. It will be Britain’s first combat test aircraft since the Eurofighter Typhoon almost 40 years ago. It is also a critical first step if the UK and its partners Italy and Japan are to achieve their promise to have new generation aircraft flying by 2035 as part of the trilateral Global Combat Air Programme (GCAP).

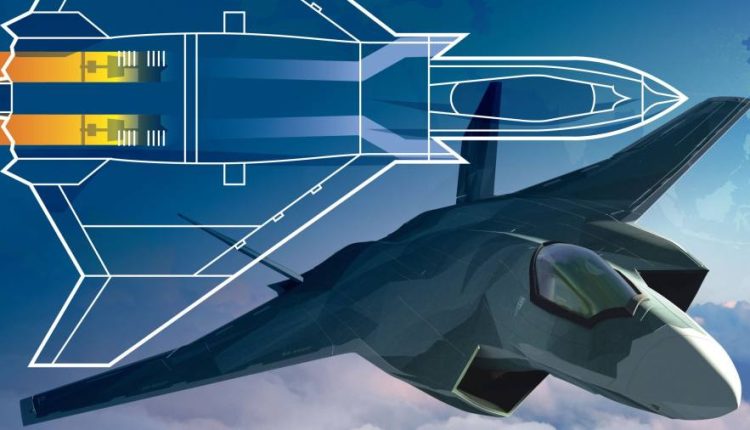

Unveiled last December, GCAP is one of the most ambitious military programmes ever attempted. It merges Japan’s F-X programme with the UK and Italy’s Tempest project, with the aim of delivering a supersonic jet in roughly half the time — and therefore at significantly less cost — of previous generation aircraft such as the Typhoon.

Previously in charge of the Eurofighter consortium, Herman Claesen, managing director of Future Combat Air Systems at BAE Systems, said a radically new approach was needed compared with the Typhoon programme, which took about 20 years to develop.

“There is not enough money, there is not enough time,” he said adding: “We’ve got to break this curve [of long lead times and soaring costs].”

Fighter jets are the most technologically complex and notoriously expensive aircraft. America’s latest-generation F-35 initiative is the most expensive military project in history, costing the Pentagon an estimated near $1.7tn to buy, operate and sustain over its lifetime.

While the cost of each aircraft depends on a range of factors including the model, some estimates cited for the F-35 jet are more than $170mn. The unit cost of the latest version of the Eurofighter Typhoon — which is one generation older than the F-35 — is in the order of $110mn-$120mn, according to analysts.

The war in Ukraine has underlined the importance of defence industrial sovereignty but the partners in GCAP know that a new, more technically advanced, fighter programme must be more affordable.

Norman Augustine, a former chief executive of US defence group Lockheed Martin, famously predicted in the 1980s that given the exponential cost of new military aircraft, by 2054 the entire defence budget would be able to afford just one single jet.

GCAP is not just an aircraft but will include manned and unmanned drones, as well as laser weaponry.

The UK government has so far committed just over £2bn towards the original Tempest programme alone, with industry partners investing about £800mn. Japan’s defence ministry is seeking to set aside ¥72.6bn ($494mn) for the GCAP programme for the 2024-2025 fiscal year.

The money will fund the so-called “concept and assessment phase” until the end of 2025. The aim then is to launch the development phase between the three nations.

To meet the ambitious timetable, the leading industrial partners on the programme — BAE, Italy’s Leonardo and Japan’s Mitsubishi Heavy Industries — are investing heavily in digital design and innovative prototyping and engineering methods. Robots used in car plants have been modified to operate at the tolerances required for military aircraft and will work alongside people.

BAE, for example, has started to use 3D printing to make moulds that will be used to manufacture carbon fibre components. These “mould tools” are usually made from steel and take about 26 weeks to make. Using 3D printing, the company can print them in under 12 hours and have a fully complete tool ready in under three weeks.

Using digital modelling will help engineers to collaborate on the design, to understand problems earlier and to speed up the regulatory certification process by reducing the need for expensive physical prototyping.

“We think the digital collaborative working environment we are setting up between Japan and Italy will be one of the most complex and biggest globally,” said Claesen on a tour of the BAE’s Warton site.

The company stresses the progress it has made. Rolls-Royce, one of the three companies working on the engine, has been testing advanced technology for the plane in Bristol, while successful ejector seat trials using a rocket-propelled sled travelling at speeds of more than 500mph have also taken place.

While work is continuing at pace on setting up the “digital enterprise”, the partners must still decide what kind of industrial structure to use to deliver the programme, given the number of parties involved.

Douglas Barrie, senior fellow for military aerospace at the International Institute for Strategic Studies, said for the programme to work “you need industry, government and defence ministries all to buy in that the key authority rests with . . . management”.

Guglielmo Maviglia, director of the Global Combat Air Programme at Leonardo, said the partners were “getting closer to the creation of a permanent industrial construct to deliver the programme”.

He added there had been talks to “re-evaluate legacy programme structures, infrastructure and performance metrics” and create a new structure.

According to executives at Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, part of the challenge is that each of the companies wants to take the lead in the most interesting parts of the development, including the cockpit, electronics, the weapons control system and the carbon fibre wings.

“There are so many areas that everyone wants to do,” said Masayuki Eguchi, head of defence at MHI. “Ultimately, the work share will be decided depending on factors such as how much time will be required to develop the technology and how much it would cost,” he said adding that the partners have yet to work out whether the workload would be shared one-third each or whether it would be a different split.

Having worked mainly with US defence companies in the past, MHI is also learning how to communicate most effectively with their UK and Italian counterparts.

“With three countries involved, there are differences in language, culture and the way of thinking. While all three companies have experience building fighter jets, it does take time to understand each other,” said Hiroshi Umino, MHI’s deputy general manager of the GCAP programme office, adding that they often draw illustrations or write mathematical formulas to make sure they have understood each other.

One of the biggest challenges will be cyber security, given the large amount of digital development. Defence experts said one source of tension could be differences in cyber security between partner nations.

Japan is allocating a portion of its increased military spending to boost cyber defences but its vulnerability to cyber attacks has come under scrutiny. The country’s National Center for Incident Readiness and Strategy for Cybersecurity revealed last month that its email system was hacked. In July, the port of Nagoya was temporarily closed by what was believed to be a Russian ransomware attack, while the Washington Post reported the discovery of a massive attack on Japan’s defence networks by Chinese military hackers carried out in late 2020.

BAE’s Claesen said security was a “key feature of GCAP” and that the different governments were “laying out the security requirements . . . often led by the UK”. Japan, he added, was “taking this incredibly seriously”.

“We believe our cyber security measures are comparable to other top-level overseas defence companies,” said Eguchi. “There is no doubt that the cyber threat will increase in line with the expansion of digitalisation but the digital tools will be adopted if the merits such as the reduction in development costs and time are judged to exceed the demerits from a certain degree of risk for data leak.”

Read the full article here