Harold Cohen was already an established painter when he started experimenting with computers in the late 1960s. This was when he began building AARON, a rudimentary AI that could draw semi-autonomously. Unlike today’s AI image generators, which make pictures based on analysing real images, AARON’s drawings were based purely on the mathematical rules Cohen programmed. Over the years, he continued to improve AARON, teaching it to draw with imprecise strokes to mimic a human hand, to detect shapes and shade them in, even to physically draw with the help of a device called a “turtle” that would scurry across the canvas making marks. One 1979 artwork is a playful piece of abstraction, reminiscent of a child’s drawing of a fantastical map. It is pretty, and looks at home on a gallery wall. Cohen would continue to tinker and collaborate with AARON for the rest of his life.

Now is a fraught moment at the confluence of fine art and cutting-edge technology. On the one hand, modern technology is being used to ever more sophisticated and captivating effect by artists. Yet simultaneously, anxiety around that same technology grows louder in artistic discourse and within the artworks themselves. With hindsight, Harold Cohen’s story looks like a parable, a possibility for an artist to neither dominate nor fear encroaching technology, but to grow alongside it.

His is one of many little-known stories told in Tate Modern’s new exhibition Electric Dreams: Art and Technology Before the Internet (opening on November 28), which brings together work from more than 70 artists inspired by and creating art with technology between the end of the second world war and the dawn of the internet as we know it in the early 1990s. This spans a period of immense technological development during which, as curator Val Ravaglia points out, the computer evolved from being the size of an entire room to a discreet box that could fit on or under a desk. The artists who harnessed and responded to this rapid social change provide an intriguing precedent for many of the conversations playing out in the art world today.

A large part of the motivation for the exhibition is to pay tribute to an often overlooked chapter in art history. While movements such as Pop art and Minimalism gained traction in the mainstream, an international group of like-minded artists gathered around the hub of Zagreb in present-day Croatia, to share work inspired by scientific and mathematical ideas. They became known by the name of their exhibition series, New Tendencies, presenting art that might today be classified as kinetic or optical art; works that either literally move or give the illusion of movement.

The group became a centre of gravity for other collectives interested in similar ideas, such as the German group Zero, founded in the 1950s by Heinz Mack and Otto Piene, and Italy’s Arte Programmata, who were inspired by mathematics and had a fan in Umberto Eco, who wrote the catalogue for their first show. The Tate exhibition also shines a spotlight on the influential 1968 exhibition Cybernetic Serendipity at London’s ICA, the first large-scale exhibition dedicated to the computer as both medium and inspiration. Footage from the show displays moving sculptures, video synthesisers, and a rather dated-looking robot that resembles an off-brand Dalek.

Art inspired by maths sounds as if it might be cold, austere and inaccessible. Ravaglia explains, however, that the New Tendencies artists saw their work as a way to make complex scientific ideas digestible, arresting, even beautiful. “You don’t need to think about what you’re seeing, it catches you and acts within your synapses first,” she says. “You enjoy the form first, then the rest comes later.” These artists provided a blueprint for the monumental, data-driven installations by artists such as Refik Anadol and Ryoki Ikeda, who display internationally today.

Much work in the exhibition hits the senses first. There is one of David Medalla’s “Sand Machines”, which drags beads across a patch of sand to create an ever-changing Zen garden, and Brion Gysin’s “Dreamachine”, a revolving lamp that creates optical patterns if you stare at it with eyes closed. The “Square Tops” sculpture by Wen-Ying Tsai, which resembles a field of elegant robotic mushrooms, undulates with lights that change frequency in response to the sound made by the people in the room. Visitors are encouraged to interact with the work by clapping, singing, or playing music out loud.

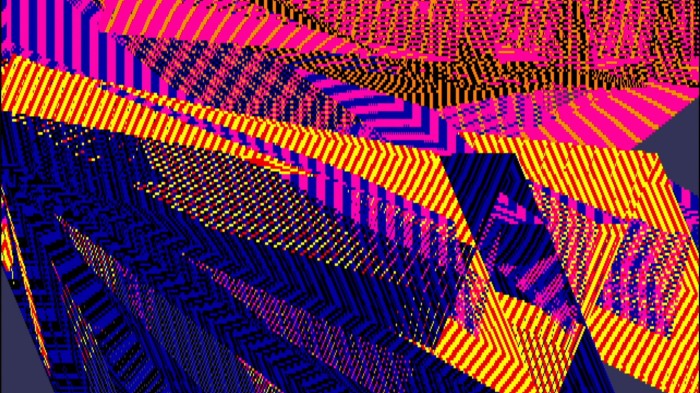

The exhibition shows that artists have long been early adopters of new technologies, with some repeatedly evolving single works as technology developed. Venezuelan artist Carlos Cruz-Diez’s piece “Chromointerferent Environment” transforms the gallery into an optical illusion where coloured parallel lines flash psychedelically across the walls. Between 1974 and 2009 he repeatedly adapted the work using novel technologies, moving from painted panels to film, then video, and finally computer-generated imagery in its current iteration.

Artists from this period offered a range of visions of the technological future in which we now live. Some gathered under the banner of sci-fi utopianism, as outlined in Richard Brautigan’s 1967 poem “All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace”, in which we live in “a cybernetic meadow/where mammals and computers/live together in mutually/programming harmony.” Others were more critical. Some artists wrote about their awareness that the technology they were using was originally developed for military purposes, and were keen to reappropriate the objects as art and sever them from this destructive history.

Particularly prescient was Gustav Metzger, who spoke of the potential environmental damage caused by technological advancements, a point that feels burningly relevant today as we begin to grapple with the energy and water resources consumed by products such as ChatGPT. “Metzger talks about how artists should be wary of embracing technology with unbridled optimism,” says Ravaglia. “It was important for them to be part of the conversation, to steer technology toward more humanistic values and not become puppets in the hands of a technological industry that would want to use artists to showcase their wares.”

Some of the vintage technology in this exhibition may look quaint today, but many of its themes address urgent contemporary conversations facing artists. “For example, some now believe that generative AI will replace creativity, that it will kill art,” says Ravaglia, “but in these works we see that the adoption of AI to make artworks has a history. There’s many examples in the past of artists that have collaborated with AIs, not just let them take over and run away with their ability to make images.”

Harold Cohen was one such example. He continued, until his death in 2016, to improve AARON the drawing AI, later programming it to be able to draw figurative images such as humans and plants, and ultimately enabling it to colour in its own drawings. “This was the point where he said: I don’t like this too much. Where’s my input?” says Ravaglia. Cohen loved to colour in his own work, so he decided to take away AARON’s ability to do so, to ensure that their work would remain a collaboration that would still bring him pleasure. He wanted to ensure, until the end, that the artist stayed in the picture.

November 28-June 1, tate.org.uk

Read the full article here