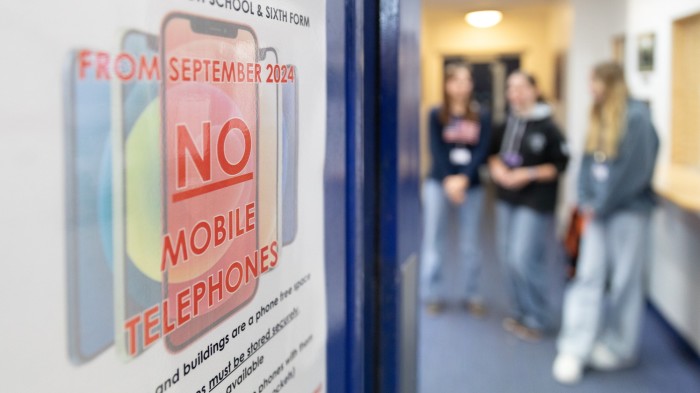

Philip Hurst is the headteacher of what he proudly describes as a “phone-free school”.

Thomas Mills High School in Framlingham, Suffolk, is among a growing number of UK schools choosing to impose strict rules on smartphones as concerns mount over their impact on children’s mental health.

Since September, the pupils — aged between 11 and 16 — have been asked to put their phones into lockers when they arrive, where they remain until the bell rings at the end of the day.

“The whole idea is that if they are out of sight, they are out of mind,” Hurst tells the Financial Times. Previously, the 1,000 children in his school were not allowed to look at phones while in lessons, but were allowed to keep phones in pockets and school bags.

Just four phones have been confiscated since the ban was introduced two months ago, he said, “whereas that would have been a daily occurrence in the past”.

The death of British teenager Molly Russell, who took her own life after viewing thousands of posts about suicide, depression and self-harm online, was one reason behind Hurst’s decision to impose a ban.

“I am seriously worried about the mental health effect of the time children are spending on phones,” he said. “I wasn’t prepared to just wait for someone to tell me I had to take action.”

Almost half the British public believe there should be a total ban on smartphones in schools, according to a poll by Ipsos for the FT.

Of the 2,175 adults surveyed, 48 per cent supported banning mobile phones in school buildings altogether, while 71 per cent said they supported asking students to deposit their phones in a basket during class.

Of those who responded, 30 per cent said they believed 11-12 years old was the most acceptable age for a child to be given a smartphone, while 28 per cent said 13-14 was more appropriate.

In April, a study conducted by regulator Ofcom found nearly a quarter of children in the UK aged between five and seven own a smartphone. A significant number used social media apps such as TikTok and WhatsApp despite being below the minimum age limit of 13.

At the same time a growing body of research is starting to demonstrate how the proliferation of smartphones and social media apps is driving an increase in eating disorders, depression and anxiety among young people.

Social psychologist Jonathan Haidt argues in his book The Anxious Generation that smart devices have “rewired childhood”. He believes smartphones should be banned entirely for children under the age of 14.

Research carried out this year by the University of Oxford found social media use in teenagers is strongly correlated with poor mental health.

The academics behind the study told the FT they had uncovered a “linear relationship” between higher rates of anxiety and depression and time spent networking on social media sites.

For schools, guidance set out by the last Conservative government earlier this year states that it is up to individual heads to decide their own policies when it comes to the use of phones. But there is a growing call from parents and policymakers to make bans a statutory requirement.

“A growing body of evidence is showing that smartphones, and social media in particular, are negatively impacting children’s mental health, sleep and learning,” said Josh MacAlister, a Labour MP and former teacher, who is hoping to push his “safer phones” private members’ bill through the House of Commons next year.

The government has ruled out backing his proposal to legally mandate phone-free schools. But the MP said the government was “open minded” on other sections of the bill that were designed to make smartphones less addictive for children.

His bill would raise the age at which children can consent to data sharing without parental permission from 13 to 16, which he says would make it harder for social media companies to “make content so addictive”.

The second part of MacAlister’s bill would widen Ofcom’s powers to ensure apps’ “persuasive design features” — which the MP describes as “the bits that are addictive by design, long scrolling, nudges and notification” — are age appropriate, and not included in versions of social media used by children under 16.

Wes Streeting, UK health secretary, signalled the government’s support last month, posting on X: “Given the impact of smartphone use and addiction on the mental health of children and young people and the concerns from parents, this is a really timely debate.”

Ministers will be watching developments in Australia, where the government last week announced a ban on social media sites for children under the age of 16.

Another reason Hurst said he chose to introduce a phone ban at Thomas Mills High was the influence of a local group of parents, who are calling on schools to play a role in limiting their children’s use of devices.

Daisy Greenwell, co-founder of the Smartphone Free Childhood movement, is also based in Suffolk. The group, which initially started as a local WhatsApp group of parents pledging to hold off giving their children phones until the age of 14, has splintered off into separate groups across England and has swelled to 150,000 members.

Greenwell said it was a “no-brainer” that all schools should be smartphone free. “It gives kids six to seven hours a day in which they’re free to learn and socialise away from the addictive and predatory algorithms of Big Tech,” Greenwell said.

“Teachers tell us that smartphones are disastrous in a school context and a huge drain on their time and resources.”

As well as banning their use during the day, Greenwell would like to see schools ban smartphones entirely in favour of simpler “dumb” phones.

“It instantly levels the playing field and dissolves the insidious network effects of the smartphone — whereby kids need one solely because everyone else has one,” she said.

It is an idea that appears to be gaining traction among parents, with Virgin Media O2 reporting last month that they had seen the sale of non-smartphones double over the past year, with a “significant spike” in September.

Hurst said children who break the no phones policy at Thomas Mills High School are given detention and parents are called to collect the devices.

“Overall the ban has been responded to really positively,” he said. “The children and teachers say there is less disruption in classrooms, more eye contact and greater social engagement. We are slowly making it normal that going to school, like sitting in the cinema, is just not an appropriate place to be on your phone.”

Read the full article here