Just weeks after I had discussed everything from China to artificial intelligence over lunch in Washington with Andrew Shearer, head of Australian intelligence, one thing I had not asked him about erupted in a stunning way: domestic terrorism, in the form of the horrific Hanukkah massacre at Bondi Beach.

On the day that two gunmen killed 15 people in a terror attack on a Jewish celebration at the Sydney beach, I contacted Shearer.

Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese had vowed to dedicate every resource to eradicate antisemitism as his government came under intense pressure about whether the state had failed its Jewish citizens.

One gunman was known to the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation, the domestic security agency, but was deemed not to be a threat. Questions swirled about whether ASIO had failed in its mission.

I catch Shearer in his final week as director-general of the Office of National Intelligence. He says that as the leader of the Australian intelligence community, he has “complete confidence” in ASIO, which he calls a “world-class security service”. He says the terror attack highlighted the “sheer complexity of the current threat environment”.

Conflicting priorities are a constant battle, he says. “At different times we have had to deal with malign state actors or domestic terrorism but generally not both,” he explains. “Espionage, foreign interference and cyber attacks by foreign intelligence services are at unprecedented levels while religiously and ideologically motivated forms of terrorism remain a sickening reality.”

He has “never seen our intelligence agencies so stretched, and I know it’s the same for our Five Eyes counterparts”, he says, referring to the intelligence network that comprises the US, UK, Canada, Australia and New Zealand.

The attack cast our much calmer lunch in Georgetown in a different light.

Bourbon Steak was the perfect place to meet Shearer because the upmarket steakhouse at the Four Seasons hotel is a favourite haunt for foreign intelligence officers stationed in Washington.

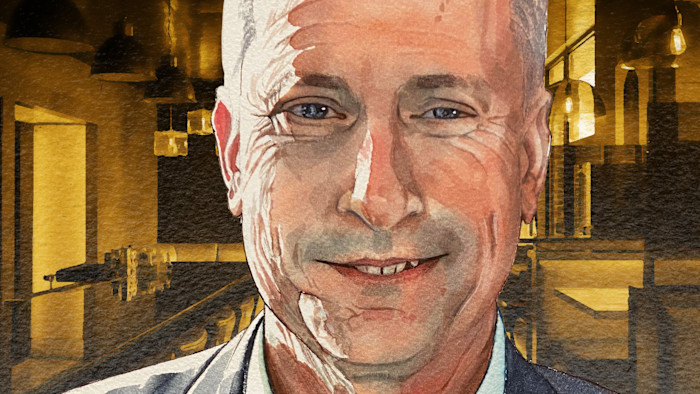

Shearer is waiting inconspicuously in a booth at the back of the restaurant when I arrive. Employing his intelligence training, he is seated on the side of the table that gives him an unfettered view of the clientele.

I first met Shearer two decades ago in Singapore. He is usually unassuming but is making me nervous. I cannot see any reading glasses and recall the time he ordered two expensive bottles of wine — on my dime — after misreading the price.

Shearer eyes the delmonico steak. “Is that all right?” he asks sheepishly. I tell him everything is fair game. “I had a look at the ($640) Japanese Wagyu,” he jests. “But I’ve got my glasses, so I steered away from that.”

Our waiter arrives. In addition to the 16oz delmonico, he orders half a dozen oysters. I get the Caesar salad and Australian Wagyu filet. We add some mashed potatoes and sautéed spinach to share. We order some wine — but by the glass, to be safe. He chooses a Californian cabernet sauvignon and I pick a New Zealand pinot noir.

Shearer, 59, has been spending a few days in Washington before ending his five-year tenure, bookending a career in intelligence that started the year the Berlin Wall came down, when he joined as a cadet. In February, he will become Australia’s new ambassador to Japan.

His career has taken twists before. He was posted to the Australian embassy in Washington as a diplomat earlier in his career and also worked at the Lowy Institute in Sydney and Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington. He served as national security adviser to Australian Liberal party prime ministers John Howard and Tony Abbott, and was cabinet secretary for a third, Scott Morrison.

Shearer is associated with the now-in-opposition Liberal party, but Albanese kept him in the intelligence job when his Labor party won in 2022. He was valued partly because of his credentials as a China hawk and deep connections in Washington.

I am curious how a lad from Melbourne ended up in intelligence. He says he was a fan of James Bond and spy novels. “I remember being in bed with the covers over my head and a torch as a young teenager.”

Shearer studied arts and law at the University of Melbourne, majoring in history and politics. But his interest in law was “desultory”, so when he saw a vague newspaper ad for a position at the defence ministry, he applied. He got the job and started working in signals intelligence, the Australian equivalent of the US National Security Agency.

His first job was in “cryptographic support”. Don’t you need to be a mathematician for that, I ask, puzzled. “I successfully completed enrolment training,” he replies with a grin. “Not saying I was a natural.”

The Australian intelligence community has changed dramatically since his early days when, he says, it resembled a “middle-aged family [with] leather patches on their jackets thinking big thoughts about the world”.

As our wine arrives, I ask what changes he has seen around the globe in his role as intelligence chief. He is struck by the speed and complexity of change. “If you think about any given week, it always feels like there’s been as much change as you might have had in a whole year before,” he says.

As examples, he cites the border war between Cambodia and Thailand, the conflict between India and Pakistan, and the 12-day war between Israel and Iran. He worries that the threshold for conflicts has fallen.

“Previously, countries would have thought longer and harder and [tried] to de-escalate. It seems that countries are more readily considering — not only considering but deciding on — military force. That’s really concerning.”

Long one of the most hawkish western officials on China, his concern has risen as its military build-up shifts the balance of power with the US.

“Even though China has some economic headwinds, it will continue to prioritise spending on the military,” he says, adding that the US and its allies, including Australia, must boost their own military capabilities.

“Not because we want a conflict, but because above all we want to have a sufficiently robust deterrent to prevent what would be a cataclysmic conflict if it were to happen in the Indo-Pacific.”

Former US president Joe Biden focused heavily on alliances to send a message to China about collective deterrence. But allies are nervous about the abrasive approach, including on trade, of President Donald Trump, I say.

Diplomatically, Shearer says allies are adapting. He cites Japan and South Korea as examples of nations that have found ways to work with Trump on trade. “Some of the heat . . . is starting to come out of that issue.”

Trump has also put pressure on allies, in Europe and Asia, to spend more on defence, I note. Shearer points out in return that many US presidents unsuccessfully tried to convince Europe to boost spending.

“Some of those were pretty articulate, pretty persuasive guys and nothing happened,” he says. “So maybe it did take a different, more abrasive approach.”

Shearer gained notoriety in Beijing in 2024 after warning that an “emerging axis” — China, Russia, Iran and North Korea — was creating a strategic problem for the west. Global Times, the state-run tabloid, slammed him in a column accompanied by a cartoon of a kangaroo wearing “cold war mentality” glasses.

“I particularly like the cold war glasses,” he jokes. “I have a framed copy of the cartoon in my office.”

Shearer thinks the west underestimated the rising co-operation between China, Russia, Iran and North Korea, partly because analysis was siloed. “We’ve missed a bit of a trick when it comes to the axis of authoritarianism.”

“The most dramatic wake-up moment was the deployment of 12,000 North Korean troops to fight against the Ukrainians,” he says, explaining that it freed Russian troops to continue an offensive in eastern Ukraine.

“We’ve created a kind of straw man argument that it’s not like a Nato alliance. That’s kind of not the point,” Shearer says. “It’s a very significant development that we need . . . to be more thoughtful about pushing back and disrupting.”

One example of closer ties between China, Russia and North Korea, which Shearer describes as one of the “most telling moments” of his tenure, was the military parade in Beijing in September when Xi Jinping hosted Vladimir Putin and Kim Jong Un — the first time the leaders of all three authoritarian regimes had met.

“Under Deng Xiaoping, China’s posture for several decades was ‘hide and bide’,” he says about China’s late paramount leader. “That parade and the assemblage of leaders of the authoritarian revisionist powers, and a much more open display of military power, was designed to intimidate and to shape international opinion.”

The People’s Liberation Army has also attracted attention as Xi has purged many top generals. What is behind the campaign? Shearer believes several factors are at play, including Xi’s focus on corruption. Another is Xi’s effort to push the PLA to meet his goal of developing the capability to attack Taiwan by 2027. A third is power consolidation, his “Stalinist impulse, to make sure that no other ultimate centres of power emerge in the system”.

The CIA calls China a “hard target”. But, I inquire, has it become even harder for intelligence agencies? Shearer says that, in some ways, it is tougher partly because China has made it much tougher to obtain many kinds of data. “But by the same token, especially under Xi, China’s behaviour has just become much more overt and obvious.”

Does his team have a good handle on China? “Our insights on China are pretty good, but our analysis can always be better,” he says, before adding something his Tokyo embassy should note: “I’m a hard taskmaster.”

One critical facility that helps Australia and the US monitor China is a satellite command centre called Pine Gap in Alice Springs.

In 2022, I travelled with Admiral John Aquilino, then head of US Indo-Pacific command, to Australia. On one leg, Aquilino gave Shearer a ride on his military jet from Canberra to Alice Springs where they visited Pine Gap — the subject of an eponymous television show. I watched an episode but was bored. What marks out of 10 would he give it?

“Three,” he says, making clear his view is not just about the acting. I press him. Does it explain the importance of Pine Gap to monitoring China? “Obviously I cannot comment on that, but I don’t think it would be a reliable guide.”

Our steaks arrive. His is not quite the “tomahawk” slab he enjoyed at a restaurant the night before. But it dwarfs my meagre 6oz.

As we dig in, I ask to what extent Australian intelligence has embraced AI? He says it is a “major priority”. It helps analyse massive amounts of open-source information, which is very powerful, notwithstanding the “mystique” around classified intelligence, he says. Tech groups are more willing to work with security agencies because of the realisation that tech is at the “centre of the struggle” in a very dangerous world.

We are meeting one month after Trump welcomed Albanese to the White House and provided a ringing endorsement of Aukus, the 2021 Biden-era security pact between the US, UK and Australia that will enable Canberra to procure a fleet of nuclear-powered attack submarines.

Shearer was arguably the key driver. He had no doubt Trump would back Aukus, despite a Pentagon review, but says the endorsement “exceeded my expectations”.

The 2021 deal resulted in Canberra spiking a submarine contract with France, which infuriated President Emmanuel Macron. Shearer says the countries have since “made up” and stresses that he has an excellent relationship with his French counterpart.

Is he practising his diplomatic skills ahead of the move to Tokyo? “I’ve still got my training wheels on,” he jokes.

Nuclear-powered submarines can travel farther without having to surface, which will allow Australia to work with the US to enhance deterrence in the Indo-Pacific. The need for this was underscored this year when Chinese warships circumnavigated Australia for the first time.

How big a wake-up call was that, I ask? “I don’t think there was a parting of the skies and a choir of angels, but it was significant,” he says. “It was designed to signal to us China’s ability to project power and sustain power, and its intention to continue doing that in the future in the waters and the skies proximate to Australia.”

Later, I ask him about Trump’s new National Security Strategy (NSS), which outlines security threats from Beijing without mentioning China by name, a move that some experts have interpreted as a softening in the US’s approach.

“I can understand some of the consternation about the NSS, but from my perspective there’s actually a lot to like,” Shearer says.

He points to the document’s clear commitment to work with allies to prevent the emergence of dominant adversaries in the Indo-Pacific. And he sees a “refreshing emphasis” on new capabilities to protect the “first island chain”, which runs from Japan to Indonesia. He also likes the “strong focus on deterrence to prevent war, including over Taiwan”.

As China continues to step up military exercises around Taiwan, how worried is he about Beijing taking military action against the country?

“The situation is deteriorating and becoming more dangerous,” Shearer says. “It’s not the only flashpoint that could lead to a catastrophic war in the Indo-Pacific, but it is probably the most dangerous.”

When Shearer arrives in Japan, Taiwan will be on his radar. China reacted furiously to Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi saying in November that a Chinese attack on Taiwan would justify Japan deploying its military. “It’s not surprising China would hope to test a new Japanese leader early. I’ve been impressed by her response,” he says.

Shearer stresses the need for allies to support each other when they face economic coercion or pressure from China. “It’s important that we have the broadest number of countries possible saying this is not OK.”

The waiter is hovering. We want coffee. Shearer orders a piccolo and looks to me for support when the waiter is flummoxed. Is that some fancy Aussie drink, I ask? “We’ve always got fancy coffee,” he beams back with pride. It’s something between a cortado and macchiato.

Shearer is excited about moving to Japan. Beyond the diplomacy, he wants to learn more about Japanese art, Sumo and sake. His father was a professional artist and Shearer sketches when on the road.

Over decades visiting Tokyo, he has spent most of the time in government offices, so is keen to travel. “One of the really exciting things about this job is I’ll be able to get on a train and explore Japan,” he says.

As we are wrapping up, I tell him that former US ambassador Rahm Emanuel loved trains and would tweet out his progress towards his goal of taking 60 trips on the bullet train during his time in Japan.

Shearer sees that as a challenge. “Surely I can do better. Australians like to do better — especially in contests.”

Demetri Sevastopulo is the FT’s US-China correspondent

Find out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend on Instagram, Bluesky and X, and sign up to receive the FT Weekend newsletter every Saturday morning

Read the full article here